The interesting thing about studying history is how the past can almost always be used to illuminate our present

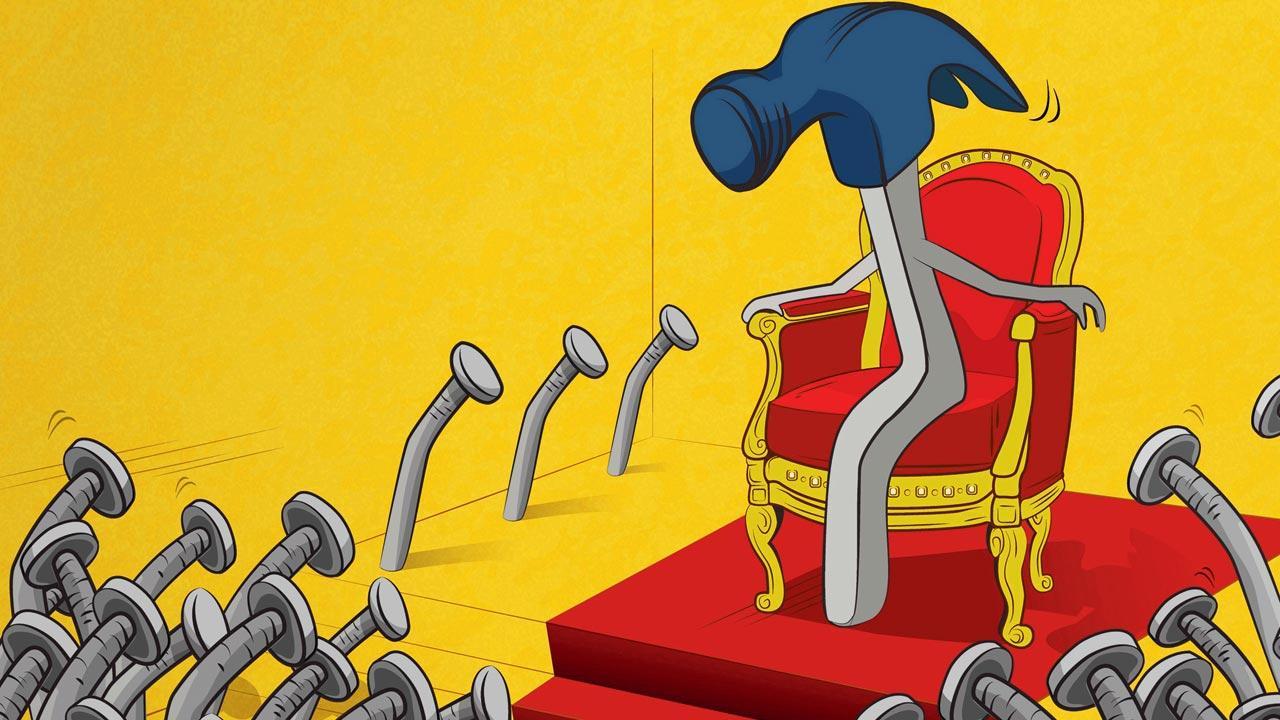

All dictators recognised the ease with which people could be made to follow them like sheep, the minute they claimed to be able to represent a majority. Representation pic

I have no specific reason for writing about dictators in this column. It’s not an anniversary or anything. Dictatorships have not really been on my mind lately, nor do I have any reason to connect anything happening in India with the trauma and brutality commonly associated with those regimes either. I suppose I thought about them simply because the mind can sometimes trick us into thinking about awful things precisely when we are enjoying our most pleasant moments.

I have no specific reason for writing about dictators in this column. It’s not an anniversary or anything. Dictatorships have not really been on my mind lately, nor do I have any reason to connect anything happening in India with the trauma and brutality commonly associated with those regimes either. I suppose I thought about them simply because the mind can sometimes trick us into thinking about awful things precisely when we are enjoying our most pleasant moments.

India is currently going through what I’m informed by Twitter to be the most prosperous time in our history as a country. Unemployment and poverty have almost been erased, according to what I have seen on several news channels lately. This has also been confirmed by some Bollywood stars, which means it’s true. The rupee is probably stronger than it has ever been against the dollar, going by what a heavy-breathing cult leader predicted a couple of years ago. Also, women, children, minorities and Dalits have never felt more loved and protected since the time Aurangzeb shed his mortal coil. So, naturally, given this state of grace, my mind wandered towards dictators and what they all seem to have in common.

Divinity was the first thing I thought of. This need to be perceived as blessed, or better, or more impressive than anyone else in their vicinity. Hitler had it in spades, as did Mussolini, and Stalin, and Mao. They encouraged their followers to look upon them as special people who could see things no one else could. Everything they did was to be applauded as an act of brilliance—or ‘masterstroke’ for lack of a better word—and celebrated on the streets. They could do no wrong and, if they did, it was never to be mentioned or discussed in public. It’s why their policies, economic or otherwise, all led to ruin, but were only talked about after their deaths.

Then there was that proclivity for violence, often pushed to the limit, and always leading to horrific crimes against humanity. It’s why so many people died on their watch, some because they were referred to as termites and inferior beings, others because they didn’t show enough respect, still others because they made the mistake of possessing the wrong belief systems. How they died was less important than why they had to, because these dictators used acts of terror against their fellow citizens to gain power. They used their own prejudices to stoke fear, because they internalised the lesson that it is always more powerful than love.

I think about their obsession with perception too—their obvious need for being photographed in public whenever possible, and how they relied upon state-sponsored propaganda units to embellish their image all through their time in power. It’s why their faces began to appear on street corners and political rallies, surrounded by halos, making them all seem like the benevolent human beings they never were. They didn’t have access to smartphones, Photoshop, and public relations teams, luckily, or one could easily see them followed by cameramen as they paid visits to their ailing mothers on public holidays.

There was also a need for approval from the world outside, sometimes tipping over into a need for control of land outside their borders. Luckily, this was restricted to dictators who ordered their armies into enemy territory, not the ones who fiddled while neighbouring countries made inroads into their own lands. I mention this because another thing dictators have always had in common is cowardice. It is numbers that prop them up, and blind support from people as prejudiced as they are. It’s also why they avoided press conferences. Questions made them nervous.

Finally, there was that habit of relying on religion to further their interests. While some dictators like Stalin made themselves out to be messiahs of sorts, others like Mussolini shoved religion down the throats of everyone in their country, insisting on the importance of one god over all others. They all recognised the ease with which people could be made to follow them like sheep, the minute they claimed to be able to represent a majority. It was their tacit acknowledgement of how prejudices that run deep can be used to seize power and hold on to it.

I’m glad we don’t have to think about dictators in a country like ours, where our fundamental rights—to equality and freedom, against exploitation, to freedom of religion, property, culture, education, and constitutional remedies—are under no threat whatsoever.

When he isn’t ranting about all things Mumbai, Lindsay Pereira can be almost sweet. He tweets @lindsaypereira

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!