How a seemingly forgotten man living on a narrow pavement in bustling Mumbai can be a lesson in foresight, planning and practical sense

The man did not quite fit into common terms like beggar, vagrant, tramp, drifter or any of their nuances, judged by his attitude, demeanour or even lifestyle

The scrawny and shrivelled man is one of the two crore proud denizens of Mumbai, India’s densest, second highest populated, and inarguably the most opulent metro.

The scrawny and shrivelled man is one of the two crore proud denizens of Mumbai, India’s densest, second highest populated, and inarguably the most opulent metro.

He is one of the 140 crore proud citizens of Mera Bharat Mahaan, the world’s largest democracy and oldest civilization.

And, of course, he is an integral constituent of planet earth’s eight billion homo sapiens.

That perhaps is the best way to introduce someone I have never spoken to or known, only seen. I have been seeing the man for a long time now, and only curious to know more a

bout him.

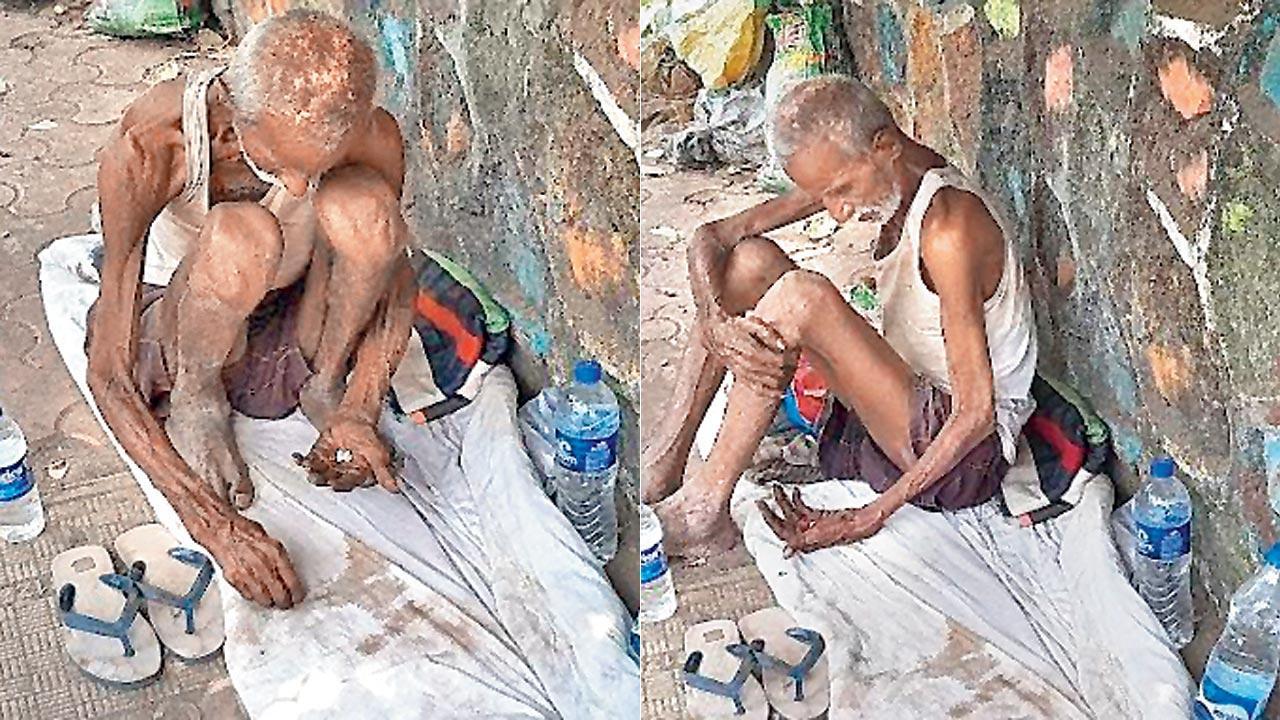

Yet, whenever I have attempted an “audience” with him, I have seen the grimly quiet man relaxed in a nap or siesta. He was mostly stretched out on a dusty white sheet on the pavement’s hard surface, his arms collapsed over his chest. His somewhat sinewy, bony legs were crossed. Head cushioned by a stuffed gunny bag of what possibly were his earthly possessions, his half-closed eyes served virtually as a “Don’t disturb” warning.

After observing the man for several days, I was counselled enough to conclude against venturing to talk to him. For, he defied description or definition; he did not quite fit into common terms like beggar, vagrant, tramp, drifter or any of their nuances, judged by his attitude, demeanour or even lifestyle. He could at best be categorised as a homeless person. But even that did not look right.

For, Mr. Anonymous occupies a strategically selected spot for spending much of what looked like his sunset days. With great care, he has chosen a coffin-sized well-shaded space right below the lushest evergreen tree alongside the parapet of a public park located at a major road intersection in North Mumbai’s Borivali West.

What’s more, in the vicinity of his command are a big mall, a busy police chowki, a tea stall that perennially draws a host of autorickshaw drivers for its customers, an inexpensive 24x7 eatery, a well-maintained public park, and, most importantly, a couple of permanently abandoned private cars parked alongside offering formidable privacy and protection.

All of which go to make Mr. Anonymous’s habitat—a sandwiched alcove on the narrow pavement between the park’s boundary wall and the discarded cars—among the most cushy dwellings he can aspire for. Which, in turn, highlights the man’s capability in scouting for a safe shelter in space-starved Mumbai, demanding foresight, planning and practical sense.

And Mr. A’s solo occupancy, taciturnity and aloofness portray him as more independent, more organised and more resourceful than most people in Mumbai may afford.

What equips the man with such confidence, energy and appetite for life, even as one without any attachment or evident means of support, leaves one in awe.

For all one can see, Mr. A, too, may have an untold story of his own—as do today’s 21 million Mumbaikars—a Bahadur Shah Zafar that Dame Fortune has failed to smile on.

That morning as I crossed his fiefdom, I watched Mr. A carefully bring out a plastic pouch from his sack, download a sheaf of coloured strips of medicines, diligently pick out the ones he needed immediately, and pop them into his mouth one by one, followed by gulps of water from one of the PET bottles he had methodically lined up against the wall, before repacking his medical kit to return it to its place.

Mr. A watched his admirer through his half-closed eyes and, wearing a philosopher’s smile, waved with a gesture that seemed to say “one more day”.

As I turned to leave, my neighbour, Kamat, who probably had been watching me intently observing the mendicant, said in a voice tinged with pathos and pity: “There’s no Mumbai… without them”.

Kamat’s remark transported me to the ‘sixties, resonating the unforgettable words of film world’s celebrated genius, Satyajit Ray.

I was at Manik-da’s South Kolkata home on an errand assigned by the Federation of Film Societies of India, waiting for the master to be free from an animated discussion—or, was it a debate?—with a visitor.

Much of the verbal exchanges between the two, no doubt, went over my head, yet snatches from them did fascinate the mind of even a lay person like me, barely out of his twenties.

And the one line the legend rounded off the session with remains indelibly etched on my mind to this day: “Can we think of the moon without its scars… the craters?”

The writer is a former political aide and the author of a short stories collection, Omnium Gatherum

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!