The passing of a Kathak legend has once again led to murmurs that point to the exploitation of students by renowned gurus. Insiders say, reporting abuse demands support, and the guru-shishya parampara offers none

Representation pic

Soon after the passing of Pandit Birju Maharaj, one of Kathak’s most famous names, on January 17, posts and threads appeared on social media detailing disturbing experiences involving the late exponent and Padma Vibhushan awardee. “Serial sexual harasser Birju Maharaj, whose unchecked predations drove away so many students from Kathak, dies at 83 without being punished or even formally called out by the Indian classical dance community,” wrote one user on Twitter. Posting a picture with Maharaj, Kathak dancer Naina Roychowdhury Green wrote on her Instagram: “Saswati Didi [Saswati Sen; dancer and senior disciple of Maharaj] would cry to me on my bed and tell me stories of how BM [Maharaj] would ask her to find more young Kathak dancers, some of these girls were teenagers, and she would weep as they often disappeared into his bedroom, sometimes two at a time,” adding, “This is a translated secret I swore to keep that I betray uncomfortably. I believe the teller of this story with all of my heart.” She has since shared accounts of other voices describing similar experiences.

(Left to right) Dhrupad stalwart Pt Ramakant Gundecha was accused of rape, and his percussionist brother Akhilesh of sexual abuse; an FIR was filed in Delhi after a Kathak student accused Pt Ravi Shankar Upadhyay of alleged molestation

(Left to right) Dhrupad stalwart Pt Ramakant Gundecha was accused of rape, and his percussionist brother Akhilesh of sexual abuse; an FIR was filed in Delhi after a Kathak student accused Pt Ravi Shankar Upadhyay of alleged molestation

The allegations against Maharaj, all unconfirmed, are the latest in a string of explosive exposes in the Indian classical arts world in recent years. In September 2020, the well-known Dhrupad Sansthan in Bhopal, which attracts hundreds of students from across India and the West, found itself in the middle of a storm with its gurus late Ramakant Gundecha and his brother Akhilesh Gundecha accused of sexual assault by several female students of the school. While Pt Ramakant passed away in 2019, Umakant and Akhilesh, a percussionist, denied the allegations through their lawyers, attributing it to vested interests. Three months later, Pt Ravi Shankar Upadhyay, a noted pakhawaj player and a guru at Delhi’s Kathak Kendra, was arrested for alleged molestation after a 23-year-old student, who reportedly had been learning Kathak at the institute for 11 years and was under the tutelage of Pt Jai Kishen Maharaj, Pt Birju Maharaj’s elder son, registered an FIR at Chanakyapuri police station. Media reports had said that the student had called Suman Kumar, the director of the institute who wasn’t available to meet, and she was asked to put in a written complaint. She sent an email to Kumar and then lodged an FIR and on the morning of December 15, Upadhyay was arrested from the institute.

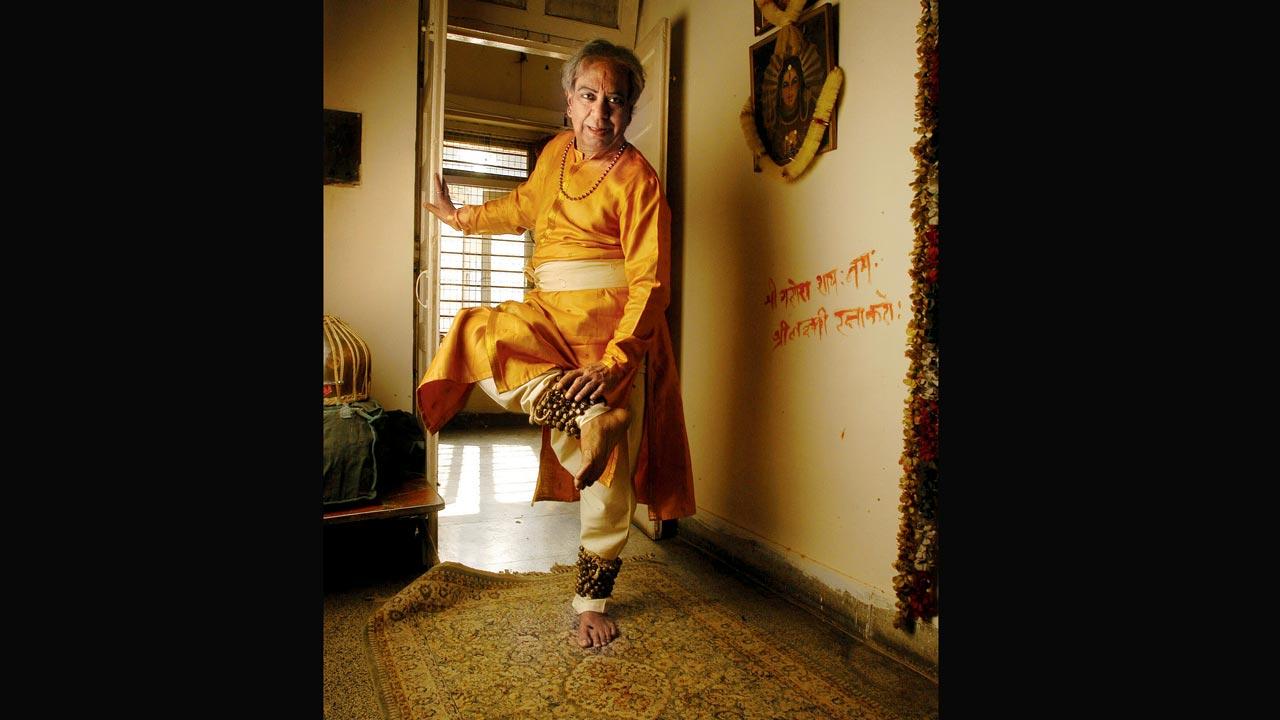

After the passing of Pandit Birju Maharaj, one of Kathak’s most famous names, this month, posts and threads appeared on social media detailing disturbing experiences involving the late exponent. Pic/Getty Images

After the passing of Pandit Birju Maharaj, one of Kathak’s most famous names, this month, posts and threads appeared on social media detailing disturbing experiences involving the late exponent. Pic/Getty Images

Allegations emerged in the Carnatic music world too in 2018, but the conversation didn’t sustain because of the silence that has enveloped such discussions in the classical arts even though insiders say, these have long remained open secrets.

Pt Ravi Shankar Upadhyay, a noted pakhawaj player and guru at Delhi’s Kathak Kendra, was arrested in December 2020 for alleged molestation after a 23-year-old student of the institute filed an FIR. Pic/The Anad Foundation

Pt Ravi Shankar Upadhyay, a noted pakhawaj player and guru at Delhi’s Kathak Kendra, was arrested in December 2020 for alleged molestation after a 23-year-old student of the institute filed an FIR. Pic/The Anad Foundation

The guru-shishya tradition, at the heart of the Indian classical arts, and its inherent power asymmetries have been at the centre of conversations around sexual harassment. Mumbai-based Kathak dancer Uma Dogra says that we cannot generalise and say that the parampara as a whole enables this behaviour, as the onus ultimately is on the guru. “To me, it is a pure relationship, associated with devotion. The guru has trodden a path of learning which is her/his duty to pass on,” she notes. However, there is a mysticism associated with the idea of the guru that places them in a position of power that is psychological, emotional, even spiritual, says Carnatic vocalist TM Krishna. While sexual predatory behaviour is an extreme situation, there are many layers to it such as creating a toxic environment, pitting one student against the other, controlling the student’s professional growth, threatening them with fewer opportunities, he notes. “There are complex power webs that a guru can very easily throw around the students,” he tells mid-day.

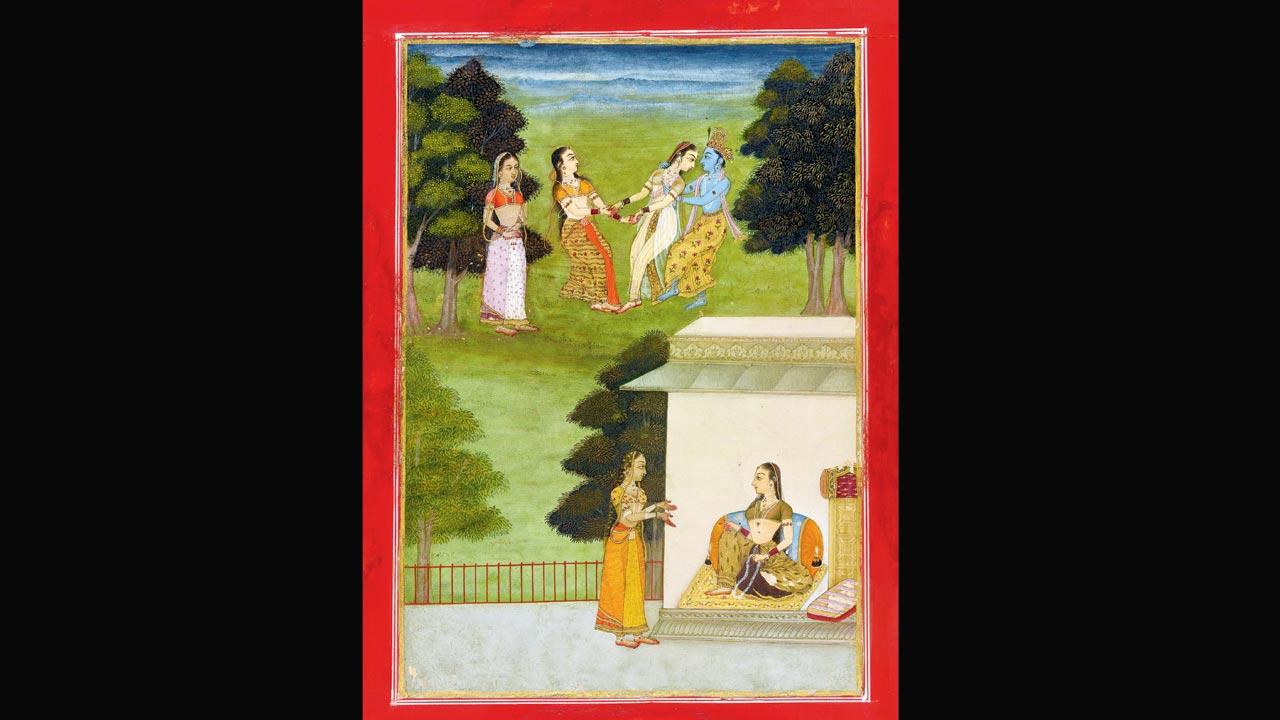

Krishna playing with gopis, folio from a Rasikpriya, dated 1686 (Samvat 1743). Artist Ruknuddin. Pic/Heritage Art, Getty Images

Krishna playing with gopis, folio from a Rasikpriya, dated 1686 (Samvat 1743). Artist Ruknuddin. Pic/Heritage Art, Getty Images

The system does not protect the student against abuse, which he sees as the core problem. In an article on the guru-shishya dynamic in The Indian Express, Krishna writes, “What must be determined is whether the system—its core structure—is safe, respectful, and non-abusive of, students. That is, irrespective of the nature of the guru, does the system provide security and strength and empower the student emotionally and psychologically to stand on her or his own? Once this question is asked, the answer is self-evident. Like most relationships, the guru-shishya relationship is grounded in a power imbalance, but here, crucially, the inequality is celebrated. The need to be subservient to, indeed submit to, the master is an implicit necessity. Let me say it as it is: The parampara is thus structurally flawed.”

Dr Arshiya Sethi argues that Lord Krishna, often an inspiration for Kathak content, is depicted as teasing gopis. To her, this is worrisome because it legitimises ignoring consent

Dr Arshiya Sethi argues that Lord Krishna, often an inspiration for Kathak content, is depicted as teasing gopis. To her, this is worrisome because it legitimises ignoring consent

Moreover, he notes that compared to other fields, the late coming out of these stories is itself emblematic of how the classical art structure operates. “It is a niche, exclusive world where everybody knows everybody. So who is going to back you? The cases that are coming out about Birju Maharaj ji are [also] coming out after he passed away. While he was around, nobody dared even speak about these things. Except for the Gundechas expose, who has spoken about what has happened in the world of Hindustani classical music?” he asks, wondering similarly about exploitation in the Bharatanatyam world. “It is such a small world with such powerful individuals and mafia, that people are scared. One little misstep can demolish your entire life. Sexual abuse in fields that are widespread socially has a better chance of coming out because there are a range of people who can come to support you. In niche worlds, especially with caste and gender hegemony, they will not come out. We need to link this to the casteist, classist and gender-specific hegemony that exists in the classical world,” he tells us.

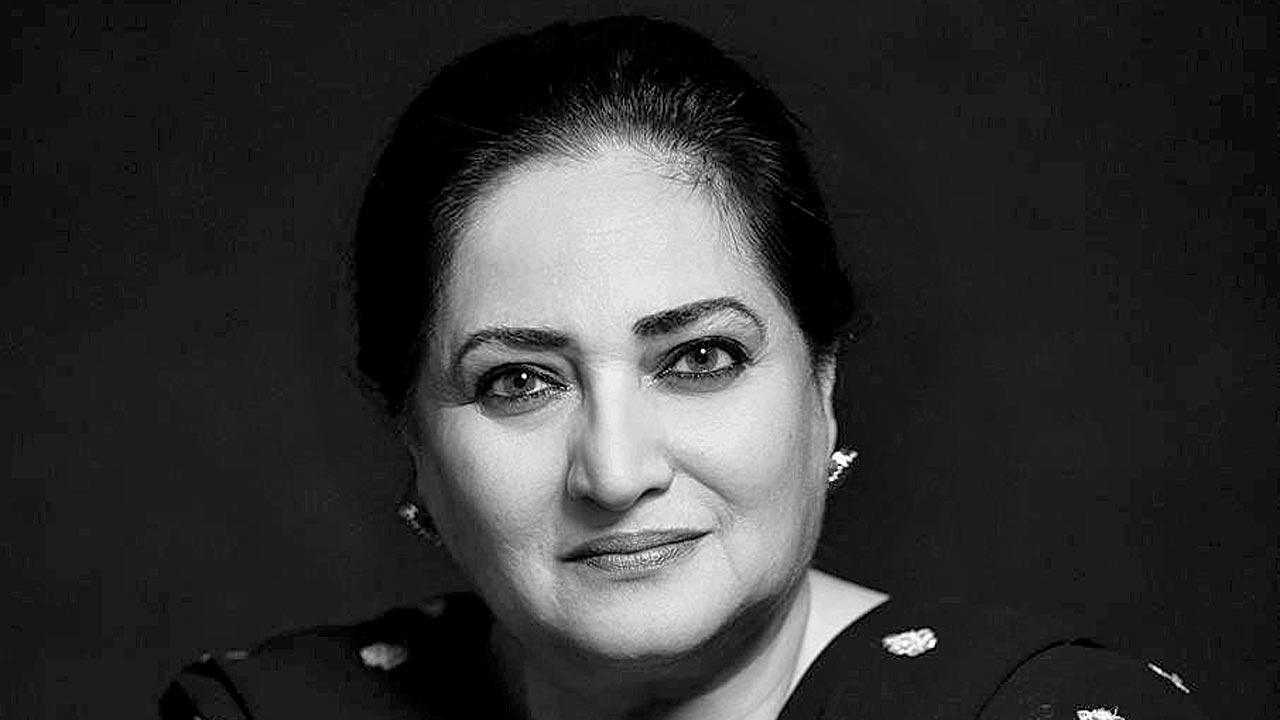

Uma Dogra

Uma Dogra

Filmmaker Chaitanya Tamhane whose 2020 film The Disciple delved deep into the world of Hindustani classical music, says that while sexual harassment within this world was not the line of enquiry he actively pursued for his film, in the course of his research, the subject frequently came up. While the fact that the experiences left deep psychological and emotional wounds was apparent, he says, there was also a palpable difficulty on the part of the victims to understand the situation because the discourse around sexual harassment is fairly recent in India although abuse has been going on for centuries. “In some cases, students had moved countries or cities to be with a guru and then were presented with this side of them… [and] it was done in a sly way where the lines were really blurred. It would start off slowly, with mind games, almost coercing the person into submission and because of the power dynamic, also withholding knowledge or favouring other students,” he shares. Tamhane’s research showed him that the world of classical music was less democratic and far more insular, with a smaller pool than some other industries. “If this is a superstar of music, he/she can still control whether you get concerts or which organisers ally with you; a lot of these people still hold a lot of clout within the circle. The students are risking their careers by speaking out.”

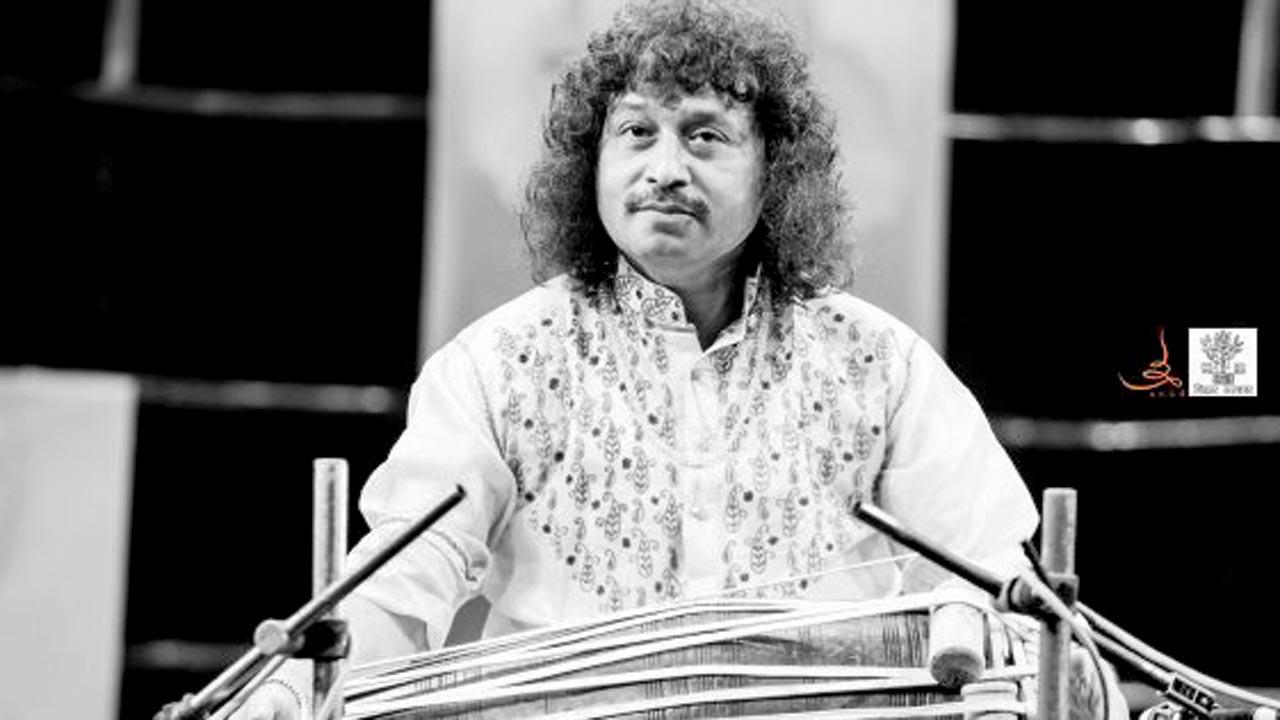

In September 2020, the well-known Dhrupad Sansthan, a residential music Gurukul in Bhopal, found itself in the middle of a storm with its gurus late Ramakant Gundecha and Akhilesh Gundecha accused of sexual assault by several female students of the school

In September 2020, the well-known Dhrupad Sansthan, a residential music Gurukul in Bhopal, found itself in the middle of a storm with its gurus late Ramakant Gundecha and Akhilesh Gundecha accused of sexual assault by several female students of the school

The culture of silence has also been associated with an argument about the importance of the art and its spread above all else. “[It] has been encouraged by those who have silently suffered and many more who have silently witnessed others being exploited. For many years these have been open secrets and locker room gossip and the very few who chose to voice out have been snubbed by the community which claims that the ‘propagation of art’ is more important,” notes Sanjukta Wagh, co-founder of the Beej School of Kathak, pointing to a patriarchal structure where blaming the survivor is prevalent. “So even today, as students open up, it is with great trepidation and caution. And a large majority choose to be anonymous.” In January last year, Beej collaborated with Dr Arshiya Sethi, a dance scholar, artivist, and founder and managing trustee of Kri Foundation that has been pushing the concerns of arts and the law, to organise UNMUTE, an initiative that seeks to be an integrated resource on various issues around arts and the law, including sexual harassment, copyright, contracts and censorship.

While sexual predatory behaviour is an extreme situation, there are many layers to it such as creating a toxic environment, pitting one student against the other, controlling the student’s professional growth, says TM Krishna, and the guru shishya system doesn’t protect the student against abuse. Pic Courtesy/S Hariharan

While sexual predatory behaviour is an extreme situation, there are many layers to it such as creating a toxic environment, pitting one student against the other, controlling the student’s professional growth, says TM Krishna, and the guru shishya system doesn’t protect the student against abuse. Pic Courtesy/S Hariharan

Kathak’s gharana system, one theory goes, started with the growth of the Indian railways in the early 19th century as artistes could easily travel from one place to another to build their recognition, observes Dr Sethi. These geographical indicators helped develop the artistes’ identities and some because of individual brilliance, had more weight than others, ultimately making them insular and secretive, and lending to them and their proponents a sense of superiority and privilege. While this could be a possible reason for the power imbalance within them, Dr Sethi feels that what is more directly responsible is patriarchy and misogyny embedded in the belief that the woman who dances is necessarily a woman who is available, pointing out how the greatest gurus have traditionally had associations with tawaifs (dancing women) and devdasis, often training them in the ways of the art. Artistic creation and the god-like position that it accords to the guru, she says, also, makes the latter unable to separate the dancing body that they have created from the dancer’s body. Kathak’s content also, she says, further renders the roles played by dancers problematic. “Kathak’s popular content is inspired by the Krishna legends. While we do ‘adhyatmic’ readings of it, some of the stories are problematic. The adoration of the maakhan chor, I feel, sends a wrong message to little children. But it is the slightly older Krishna with his stalking, teasing the gopis, ignoring consent, that is worrisome. Some of these actions are clearly defined in the law of the land as actions that could have consequences. Artistic license counters socially appropriate gender behaviour.”

The looseness with which the teaching mechanism operates in the name of tradition needs a rethink, feels TM Krishna. “Most teachers don’t have an organisation and hold private classes. How does one bring that under the umbrella of the Internal Complaints Committee (ICC)?” he asks. Dr Sethi similarly asks that when the PoSH Act came into being in 2013, which requires every company having more than 10 employees to constitute an ICC in the prescribed manner in order to receive and address the complaints of any sort of sexual harassment from women in a time-bound and confidential manner, just how many institutions of the government had the PoSH in place. Kathak Kendra, she cites, got it only after their December 15 crisis. Survivors of the

Gundecha controversy have told the media that the findings of the investigation can’t be made public. This then defeats the purpose of having these acts at all.

The solution ultimately rests in cultural and attitudinal change. “The fact that these stories are coming out has set the alarm bells ringing and I believe the next generation will learn from this,” observes Krishna.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!