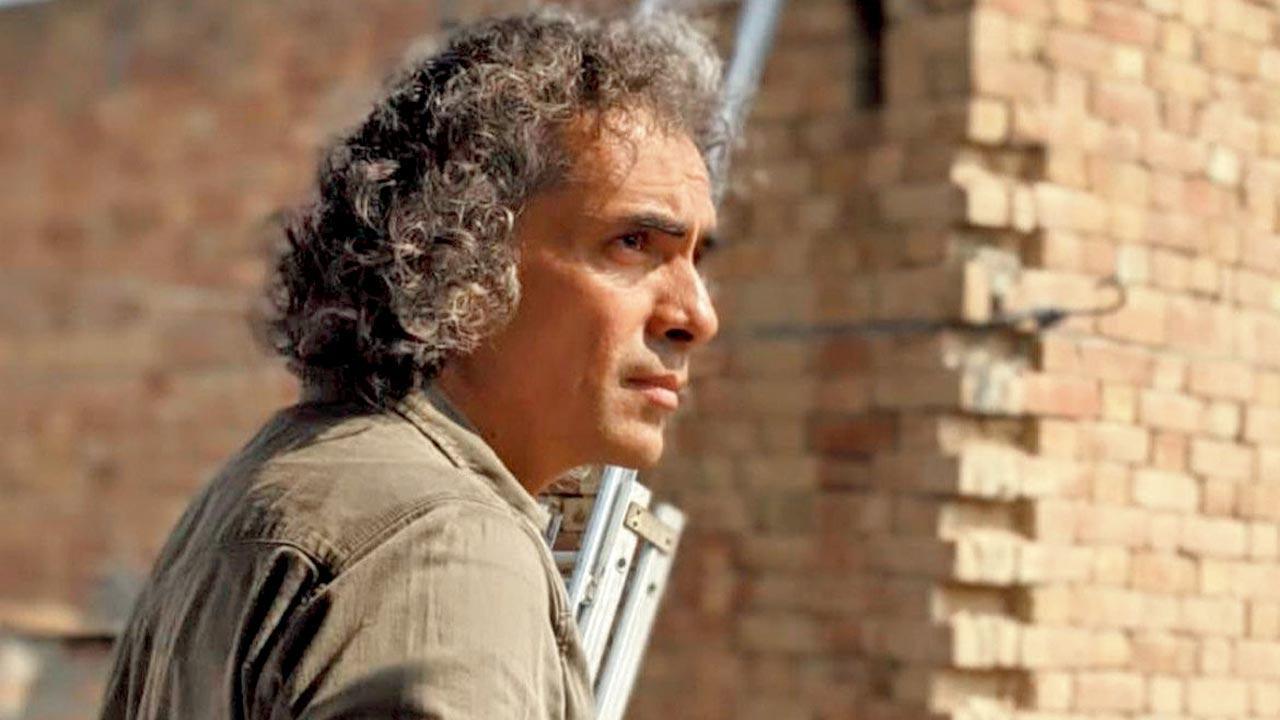

Imtiaz Ali traces the origins of Amar Singh Chamkila, an artiste whose golden phase ran parallelly with one of the worst times of Punjab. As the state burnt, an artiste was born

Ali co-wrote the movie with his brother Sajid

The last time he told the story of a musician, filmmaker Imtiaz Ali sealed his fate in the other world, which in the words of 13th century poet Rumi was “the field beyond right and wrong”. Seventeen years later, Ali tells the story of another musician, whose fate was unfortunately sealed more than three decades ago. But this time around, Rumi’s words become the beginning of the story. There’s no other way to step into the world of Amar Singh Chamkila, Punjab’s controversial yet legendary musician of all time, Ali says. “The point was to get on with it. Okay, he sang double meaning songs. You can judge him. But let’s go beyond this. Let’s not fight about whether he was right or wrong. Let’s discuss what he loved. In order to reach that, you have to go past judgement. (As Chamkila would say) ‘Theek hai, aap bolte ho, mai galat hun. Now, let’s talk about what really moves my heart.’ That becomes the bigger discussion,” he begins.

ADVERTISEMENT

Chamkila stars Diljit Dosanjh in the titular role of the musician, who composed, wrote and sang raunchy, suggestive duets with singer and second wife Amarjot during the ‘80s. The couple, along with two members of their band, were assassinated in 1988. Until his untimely demise, Chamkila remained the most popular Punjabi artiste. But, parallelly to his rise, rose the intense criticism against him, from religious fundamentalists to sections of the media, who found his work dangerous for the society. To Ali, who co-wrote the film with filmmaker brother Sajid Ali, what really spoke about Chamkila was how he became the source of cheer for the state of Punjab when it was surrounded by gloom.

“For me, the story of Punjab came before the story of Chamkila. I knew this aspect of Punjab, where grimness and celebration go hand in hand, for a long time. I have known the fact that all Indian love stories have been Punjabi love stories, from Heer Ranjha to Soni Mahiwal. I also know that the biggest tragic events in India have also happened in Punjab, including the partition and the displacement. So, there’s something very ironic about it. When I then heard the story of Chamkila and discovered more about him, I got into making this film on him because it reflected the same irony. So much so that the purple patch of Chamkila’s career was one of the worst times of Punjab, the ‘80s, when it burnt. That is when Chamkila was on fire as well. I also know this incident that a particular officer of HMV was in conversation with Chamkila and was accepting and, perhaps, even inspiring him to make more happy songs for the audience of Punjab, which was going through darkness. So, in the anatomy of this conflict are both Punjab and Chamkila. I wanted to go there,” shares the director.

A biopic was never on the cards for Ali, who has primarily helmed modern day romances. But Chamkila’s tale gave him an outlet to say things that were personal to him. “It so happened that in the story of Chamkila, there happened to be so many things that I felt I wanted to say, things that I felt were really hidden from the audience.” Through the story of a man passionately and stubbornly in love with music, Ali makes explicit commentary about an artiste’s relationship with his/her art and its impact on the society. The questions raised during Chamkila’s time, like what is good art, if seeking moral superiority from art is valid and who decides what an audience should consume remain relevant even today.

A much recent example of it is 2023’s divisive action drama film, Animal, headlined by Ali’s frequent collaborator Ranbir Kapoor. While it went on to become a roaring commercial success, it was severely panned by a section of the audience and the media for its depiction of misogyny and violence. Ali says while he takes his responsibility as a filmmaker seriously, he believes personal opinions on a film shouldn’t turn into sweeping judgments about it.

“As an artiste, when I would put something across, I will bear a sense of responsibility. Not only in terms of morality but also in terms of giving the audience something that elevates their experience. Something that they love but something that they haven’t seen before. As far as criticising a particular film is concerned, I feel that one should avoid because people should judge. We are a democratic nation, we believe in the power of people. They will decide what they want. If they don’t like a certain film, they will not watch it. Who is to decide whether it’s right or wrong? Who casts the first stone? I wouldn’t want to be that person. I can say whether I like a certain song or a film or not. I have the choice of not watching or listening. But I can’t say this is wrong to be made or wrong for people or not suitable for people so they shouldn’t be allowed to watch it. I don’t think anybody has that power to decide for people.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!