From the voice of nationalism during the freedom struggle, to standing strong during the Emergency, to serving as the carriers of awareness to the farthest corners of the nation—here’s why regional newspapers remain relevant to this day

85-year-old Khadija Khan, a veteran reader of The Inquilab newspaper at her residence in Madanpura. Pic/Satej Shinde

Before India’s Independence in 1947, regional newspapers were more than just sources of news—they were the heartbeat of revolution. They defied colonial censorship, challenged oppressive policies, voiced the public’s yearning for independence and, most importantly, spread the word about the freedom struggle to the farthest and most remote areas of the nation. While the English newspapers of the time mostly shied away from critiquing British policies, regional papers emerged as a unifying voice for Indian nationalists against the colonisers, prompting harsh crackdowns on these publications.

Urdu newspaper Pratap, for example, locked horns with the British administration within days of its launch in 1919, reporting on atrocities against satyagrahis in Delhi. “Pratap was founded in Lahore on March 30, 1919, by my grandfather Mahashay Krishan,” says veteran journalist and author Chander Mohan. “Within just 12 days of Pratap’s launch, the British shut it down. Pratap wasn’t allowed to be published or circulated for almost a year after that,” he says, adding that the paper was also barred from any coverage of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre that occurred on April 13, 1919.

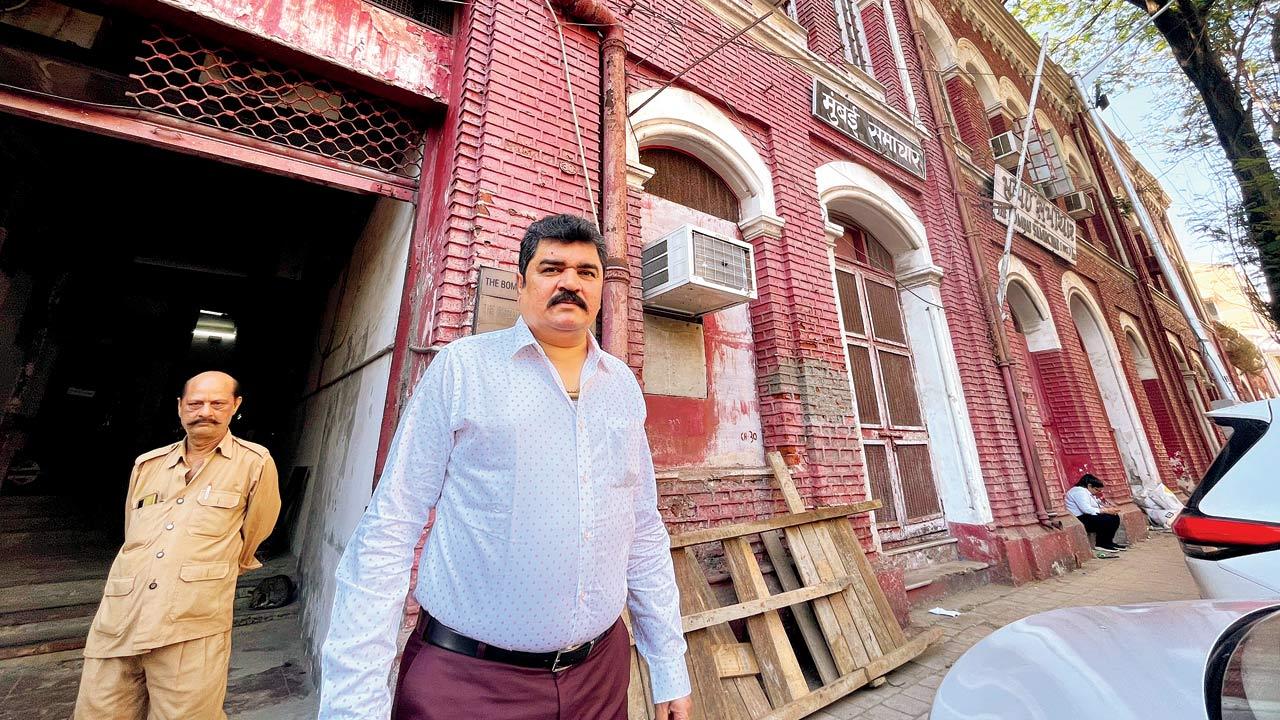

Mumbai Samachar’s Editor, Nilesh Dave at his office in Horniman Circle, Fort. Pic/Atul Kamble

Mumbai Samachar’s Editor, Nilesh Dave at his office in Horniman Circle, Fort. Pic/Atul Kamble

In Pratap: A Defiant Newspaper—a new book that’s out this month—Chander and his daughter Jyotsna Mohan chronicle the paper’s history and its bold stance against the British Raj. Chander served as the editor of Vir Pratap, the Hindi counterpart of Pratap, for 40 years until its closure in 2017. Founded in 1956, Vir Pratap continued the tradition of its predecessor. Jyotsna followed in his footsteps and has worked as a journalist at several media houses.

“My grandfather was a formidable and uncompromising man,” Chander states. “He was constantly at odds with the British and was imprisoned multiple times. This legacy was carried forward by my father, Virendra. I think it is this uncompromising legacy that both Pratap and Vir Pratap upheld for as long as they were in circulation.”

An edition of The Inquilab from 1974. Pic Courtesy/Team Inquilab

An edition of The Inquilab from 1974. Pic Courtesy/Team Inquilab

The action against Pratap was just one instance out of decades of attempts to silence Indian-language newspapers going as far back as the Vernacular Press Act of 1878, which led to heavy censorship of reports and editorials. Despite this pressure, as well as future challenges such as the advent of TV and digital media, many iconic pre-Independence publications survive to this day, from Pune-based Marathi paper Kesari, to Anandabazar Patrika in Bengali, and Mathrubhumi in Malayalam.

Among them also is mid-day’s sister publication, The Inquilab, an Urdu daily founded in Mumbai in 1938 by Abdul Hamid Ansari. The paper celebrated its 86th anniversary earlier this month.

Former Pratap Editor Virendra (extreme left) being released from a British jail. Pic Courtesy/Jyotsna Mohan

Former Pratap Editor Virendra (extreme left) being released from a British jail. Pic Courtesy/Jyotsna Mohan

During the Haripura Congress Session in 1938, Subhas Chandra Bose, as president of the Indian National Congress, declared a clear aim of achieving complete independence. Amidst this fervour, Ansari recognised a crucial gap: a lack of communication between the British authorities, national leaders, and the masses—particularly in Urdu. “Mumbai had a significant Urdu-speaking population even back then,” notes Shahid Latif, the Editor of The Inquilab. “Mr Ansari was committed to making news accessible to them.”

However, the early years were far from easy. “There was a serious resource crunch,” Latif recalls. “At one point, Mr Ansari himself would stand at the printing press, overseeing the newspaper’s production at night. He would catch a few hours of sleep in the press before delivering bundles of The Inquilab on his bicycle to vendors in the morning.”

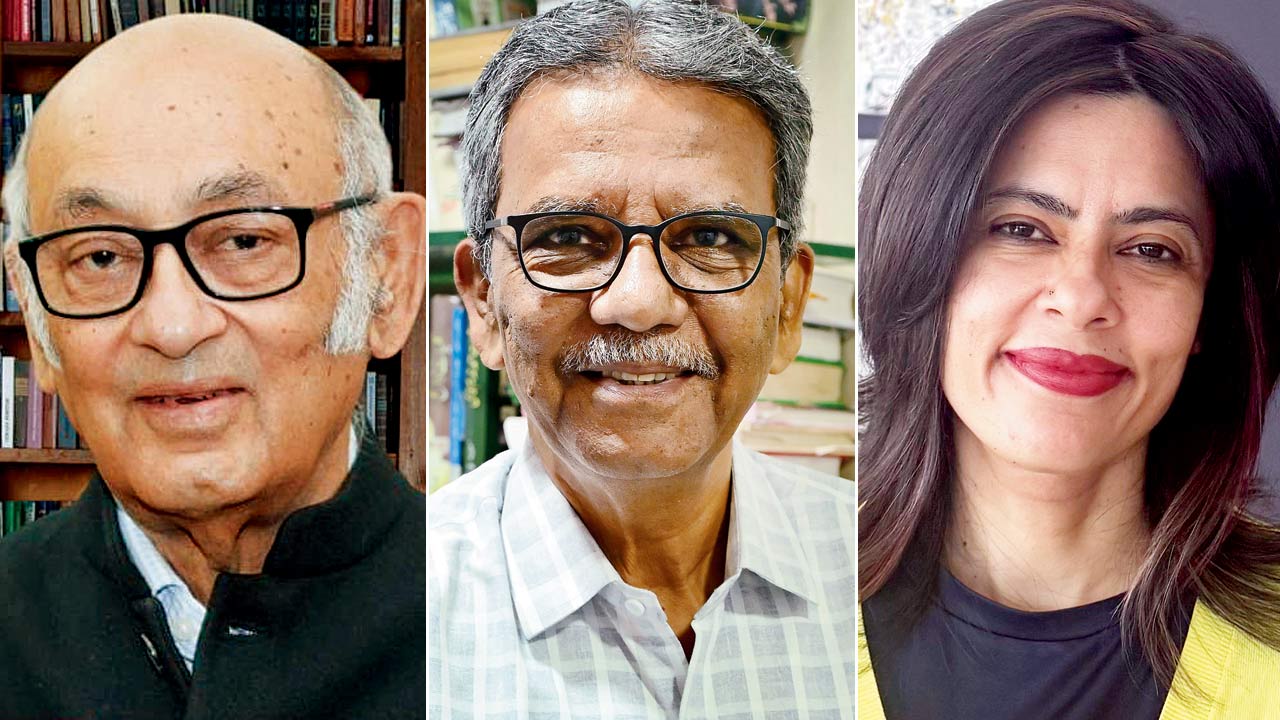

Chander Mohan, Editor, Vir Pratap; Shahid Latif; Jyotsna Mohan

Chander Mohan, Editor, Vir Pratap; Shahid Latif; Jyotsna Mohan

The over-200-year-old Gujarati daily, Mumbai Samachar (formerly Bombay Samachar), on the other hand was originally established in 1822 as a shipping trade paper. Back in the 1800s, even before the British occupied India, the city was a growing trade hub, attracting businessmen from Europe, South Africa, and the Americas. However, there was no system in place for merchants to track incoming and outgoing ships at the Bombay docks. “Mumbai Samachar initially started as a source of information for traders, publishing details about ship arrivals and departures. For the first 10 years, that was its primary purpose,” explains Nilesh Dave, Editor of the publication which is the oldest continuously published newspaper in Asia. During the Independence movement, the paper pivoted to serving as a bridge between the British and the Gujarati-speaking population of Mumbai. The newspaper provided vital information on political developments to the local community.

The post-Independence era brought new challenges for these regional papers. The fight was no longer against a foreign ruler but against the tides of

modernisation, shifting reader habits, and the dominance of English-language media. The print industry changed, governments changed, and with the rise of television and digital platforms, attention spans shortened.

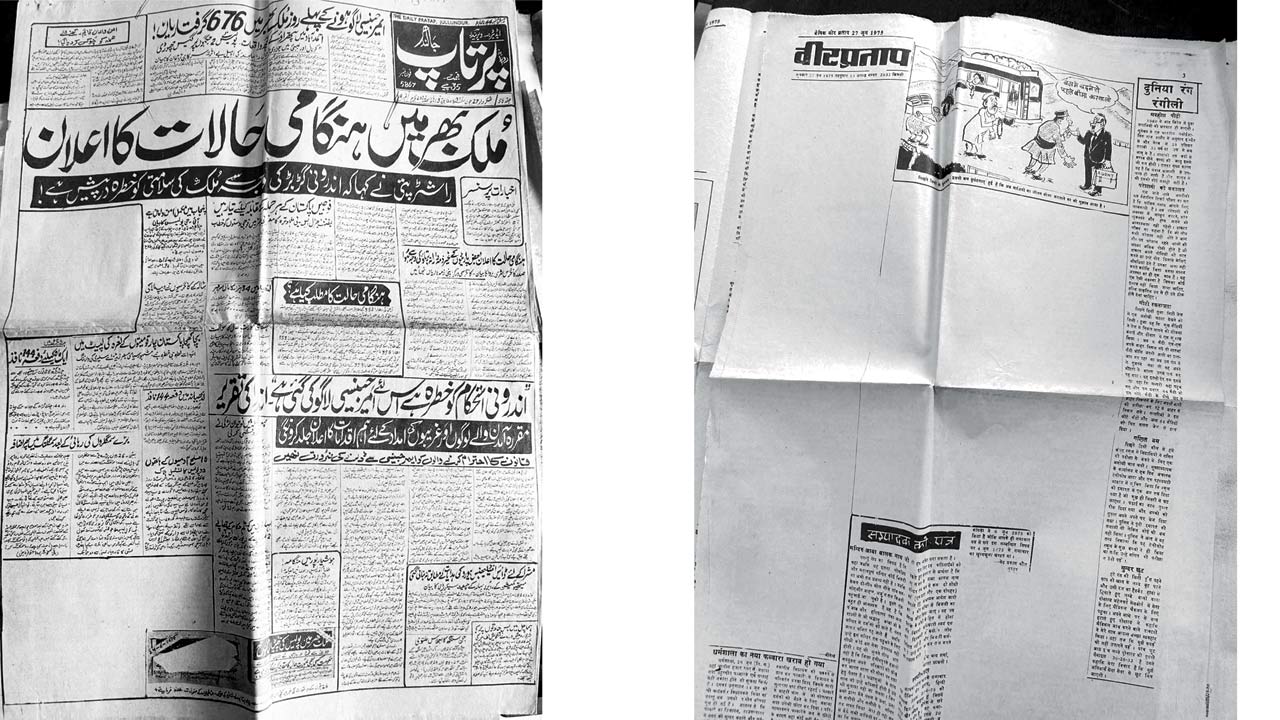

The editorial’s of Pratap (left) and Vir Pratap (right) were left blank during the Emergency in 1975. Pic Courtesy/Jyotsna Mohan

The editorial’s of Pratap (left) and Vir Pratap (right) were left blank during the Emergency in 1975. Pic Courtesy/Jyotsna Mohan

Even after Independence, Pratap and Vir Pratap’s stance remained anti-establishment. “Whether right or wrong, we kept fighting,” notes Chander. This would often lead to advertisers suspending ads and subsequent financial constraints.

Perhaps the harshest period of censorship after the British Raj was the Emergency imposed by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from 1975 to 1977. Most major newspapers were silenced—electricity to their offices was cut within three hours of the declaration, and political opposition leaders were arrested.

During this time, both Pratap and Vir Pratap would protest the government’s draconian actions by leaving sections of its editorials blank. “We soon received an order from the administration stating that blank spaces were not allowed. So instead of editorials, we began publishing general news in those sections,” Chander and his daughter Jyotsna recall. This, however, was not the only form of resistance. “Somebody suggested to my father, Virendra, that he should tell his own story and his version of the freedom struggle. So he started writing his life story on the editorial page,” Chander says.

The twin newspapers became synonymous with bold, hard-hitting journalism. “Indira Gandhi’s Emergency was stoutly opposed, with my father refusing to have his editorials censored. For 21 months, the newspapers went without an editorial section,” notes Chander.

During the Emergency, even the smallest advertisement had to be cleared by the authorities, he recalls, adding that sometimes, a junior clerk from the municipal corporation would act as a censor.

Reflecting on the paper’s editorial stance, Chander adds, “We took our crusade against the British into independent India. In hindsight, though, I feel we should have adjusted our anti-establishment position a little. For instance, Punjab’s former Chief Minister Pratap Singh Kairon was credited with turning the state into a progressive one after Partition and he is still remembered as a visionary leader. But my father had a running battle with him over corruption.”

Mumbai Samachar, on the other hand, stayed clear of much of this oppression, and was one of the few papers that continued running during this time, says Dave, adding, “Our goal has always been to report the truth without bias. Even during the Emergency, we remained a bridge between the government and the public,” he notes.

To this day, regional newspapers remain relevant and crucial in the nation, where only about 10 per cent of population speaks English, as per the 2011 census. “I believe that vernacular news reaches far more people in India, because news is one of those things that even people in the most remote parts of the country want access to,” Dave adds.

One of the biggest transitions for Indian-language papers came with the digital revolution. “Before 1991-92, every copy of The Inquilab was handwritten in Urdu by our in-house calligraphers,” recalls Latif. When computers arrived, the calligraphers saw them as a threat. Many believed that typed text was not authentic, and understandably so—their livelihoods were at stake.

“By the mid-1990s, we began printing a few pages in handwritten script while the rest were typed. By 1998, the calligraphy department was completely shut down,” he shares with sigh. At that point, The Inquilab offered the calligraphers an opportunity to transition into editorial roles. “Some of the younger calligraphers took up the offer and remain part of our team even today,” he tells us. Latif points out that regional publications, including The Inquilab, have been slower to transition to digital platforms. “This is because a large section of our readership, especially the older generation, still prefers the ritual of reading a physical newspaper with their morning tea or coffee,” he explains. Despite this, The Inquilab remains the number one daily Urdu publication in the country, as per the last Indian Readership Survey conducted in 2019.

“I have been reading The Inquilab for over 55 years,” says Khadija Khan, 85, a former schoolteacher at Urdu-medium schools in and around Madanpura. “Every day, before starting my chores, I need to read The Inquilab. It’s a habit—I feel unsettled without at least skimming through the paper. If, for any reason, I miss a day, I make sure someone at home saves it for me so that I can read it later.”

Mumbai Samachar, too, continues to have a strong readership. “Our cover price is R10, making it one of the costliest daily newspapers in India, yet our circulation remains strong,” says Dave. While he admits there’s been a decline of about five to seven per cent in print readership—much like most other newspapers—he notes that their online edition is doing exceptionally well. “Our website readership is tremendous, and to make it more accessible, our online edition is completely free of cost,” he adds.

For Pratap and Vir Pratap, however, the digital transition never happened. “We never had a digital presence,” admits Chander. “We never thought of it. We weren’t very progressive in that regard. I think that’s where we went wrong—we were so entrenched in print media that we didn’t considered anything else.”

10%

Of Indian population speaks English, as per the 2011 census

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!