Arched rooms that hold up sloping foundation in Taj Mahal’s basement don’t house Hindu idols. Nothing mysterious or worth maligning the Mughals for, say experts about a monument we should continue to be proud of

Pic/Getty Images

Back in the 17th century, Mughal emperors didn’t enter the Taj Mahal from the south door that visitors take today. They would cross the Yamuna river by boat to come to a now defunct gate. “The emperor [Shah Jahan] would walk in from the gate on the left of the northern wall, now silted up,” says Delhi-based historian-author Rana Safvi. “He would pass through the galleries and rest in one of the rooms. Amita Baig [heritage management consultant who co-authored Taj Mahal: Multiple Narratives] described these galleries as very well-painted corridors.”

It is these rooms that have been the subject of recent contention. Essentially a mausoleum commissioned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan for his favourite wife Mumtaz Mahal, the Taj was built between 1631 and 1648. Recently, a public interest litigation (PIL) was filed in the Allahabad High Court, seeking directives to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to probe the 22 closed rooms under it to ascertain the presence of idols of Hindu deities, refuelling the theory that the Taj was built over Tejo Mahalaya, as claimed by historical revisionist Purushottam Nagesh Oak (PN Oak).

Amita Baig, heritage mgmt consultant

Amita Baig, heritage mgmt consultant

A professor of History at the Aligarh Muslim University in Uttar Pradesh, Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi squashes these claims. Explaining the topography of the region and the structure of one of the Seven Wonders of the World, he says, “It is a massive and heavy structure constructed on sloping ground. The base is higher on the side of the garden and it slopes sharply towards the river. Mind you, the Yamuna that you see today was a vast river back in the 17th century. To support the structure, wells were dug [as they are for bridges] at regular intervals, lined with teakwood and filled with boulders and rubble so that the sand didn’t cave in. This made for a stable foundation. Brick platforms were built on top of these wells, held in place by arches, a technique to support heavy weights. So, a double platform was created towards the river, which sloped towards the garden. Arched rooms were created below the foundation, upon which marble was laid horizontally. These rooms had a number of purposes. During the Mughal era, the Yamuna was the main route of transportation. Large ships would navigate the river, connecting Agra to Allahabad and Bengal. When Shah Jahan or the royal family visited the monument, they would cross the river, and go into these rooms to rest.”

The foundation for the Taj goes down 17.5 metres, adds Safvi. Thus the existence of any remains of a former structure is impossible. “So, where’s the question of any rooms from Raja Man Singh’s haveli?” asks Safvi. According to the historian, the underground rooms and gallery corridors still exist, but access to them was closed in 1980 after the flood of 1978. The Yamuna overflowed that year, nearly submerging the entire old city. “These rooms were then cordoned off from the public for the safety of the monument,” adds Safvi, who says she has spent many an evening in the Taj’s gardens with her sister.

Since it was a massive construction on sloping ground, the foundation for the Taj Mahal went 17.5 metres deep. Wells were dug at regular intervals, lined with teakwood and filled with boulders to prevent the sand from caving in. On top of these wells came platforms, held together by arches, which later became arched rooms below the foundation. Pic/Getty Images

Since it was a massive construction on sloping ground, the foundation for the Taj Mahal went 17.5 metres deep. Wells were dug at regular intervals, lined with teakwood and filled with boulders to prevent the sand from caving in. On top of these wells came platforms, held together by arches, which later became arched rooms below the foundation. Pic/Getty Images

The PIL, which the Lucknow bench of Allahabad Court dismissed on May 12, was supported by BJP MP Diya Kumari, the granddaughter of the last Maharaja of Jaipur, Man Singh II. She claimed that the land on which the Taj Mahal was built belonged to Jaipur’s Maharaja Jai Singh I, and was acquired by Shah Jahan. Her purported evidence is the royal records.

Historians hold that Shah Jahan bought the land in exchange for four estates. One has to see this in the context of the relationship between the Mughals and the Jaipur royals, suggests heritage activist Sohail Hashmi. “His grandson, Man Singh I, was close to Akbar [Harkha Bai’s niece married Akbar’s son Jehangir]. In fact, Man Singh I was a senior noble in Akbar’s court and they were family. It was Akbar who granted him the land where the Taj stands today. Traditionally, these grants were not permanent, and the land would go back to the ruler once the grantee passed away; but in this case, it didn’t. Two generations later, when Mumtaz passed away, Shah Jahan selected the place for his wife’s mausoleum. His ministers would have traced the ownership of the land to Jai Singh I [Man Singh I’s grandson]. Jai Singh I, who was given the title Mirza, a title traditionally reserved for Mughal princes and nobles, was willing to gift it to Shah Jahan, but the Mughal emperor wouldn’t accept that, because as per Islam, you can’t build a mausoleum or a mosque on land that doesn’t belong to you.”

Heritage activist Sohail Hashmi says that it is a myth that Emperor Shah Jahan chopped off the fingers of artisans who built the Taj Mahal. Within 200 yards of the south gate of the monument, is Tajganj, a settlement of the artisans’ descendants. Some of them have won the President’s medal.

Heritage activist Sohail Hashmi says that it is a myth that Emperor Shah Jahan chopped off the fingers of artisans who built the Taj Mahal. Within 200 yards of the south gate of the monument, is Tajganj, a settlement of the artisans’ descendants. Some of them have won the President’s medal.

The book—Taj Mahal: The Illuminated Tomb by WE Begley and ZA Desai—details this. “Even though Raja Jai Singh I considered the acquisition of this [tract of land] to be fortunate… [he respected the importance of religious matters] and a lofty mansion from the crown estates was granted to him in exchange,” reads a line from the book.

Safvi adds that the Mughals were great recordkeepers. “In 1633,” she says, “four havelis were given in lieu of this land. Now we don’t know whether it was along with the mansion mentioned earlier or in exchange for that, but there is a farman in the now sealed Kapad Dwara collection of Jaipur City palace. Diya Kumari ji has authority over the City Palace. All she has to do is open it, and that may sort out the litigation. Not just the farman, but even the Persian translation of Mahabharata and Ramayana—commissioned by Akbar—rest there.”

Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

Why did Shah Jahan choose this particular piece of land over any other? Why wasn’t the Taj built in Burhanpur (present-day Madhya Pradesh) where Mumtaz Mahal died and was buried temporarily? Safvi has an explanation. “He had initially considered a grand mausoleum on the banks of the Tapti. But it was a challenge to transport the marble from Rajasthan to Burhanpur. The composition of the soil was also unfavourable. Raja Man Singh’s haveli in Agra was the prime location due to its position on the bend of the river where the thrust of the Yamuna was the least, and the river was least likely to meander from. If you see the Red Fort, the Yamuna has shifted five or six km from its actual location. What used to be the Yamuna is now MG Road. But the Yamuna still runs along the Taj. The river was a very important because of the heft of the structure—the dome weighs about 1,200 tonnes. Water was needed to keep the timber [lining the wells] moist, otherwise it could crack.” Plus, as a mausoleum, it had to be a sacred space. “It is not just a monument of love,” she says. “It was a monument meant for the redemption of an empress. It had to be built on a paradisical theme, incorporating all religious factors. That’s why the calligraphy on the walls is about death and redemption in heaven. A grave has to be perpendicular to the Qibla [the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca, which the Muslims face in various religious contexts, particularly for prayer] and the mosque attached to the Taj would have to face west. This was the spot where all this was aligning.”

Time and again the theory that Taj Mahal is Tejo Mahalaya, a temple to Lord Shiva, makes its way into WhatsApp groups and even on television debates. In 2000, the Supreme Court dismissed PN Oak’s petition to declare that a Hindu king had built the Taj Mahal as “misconceived”.

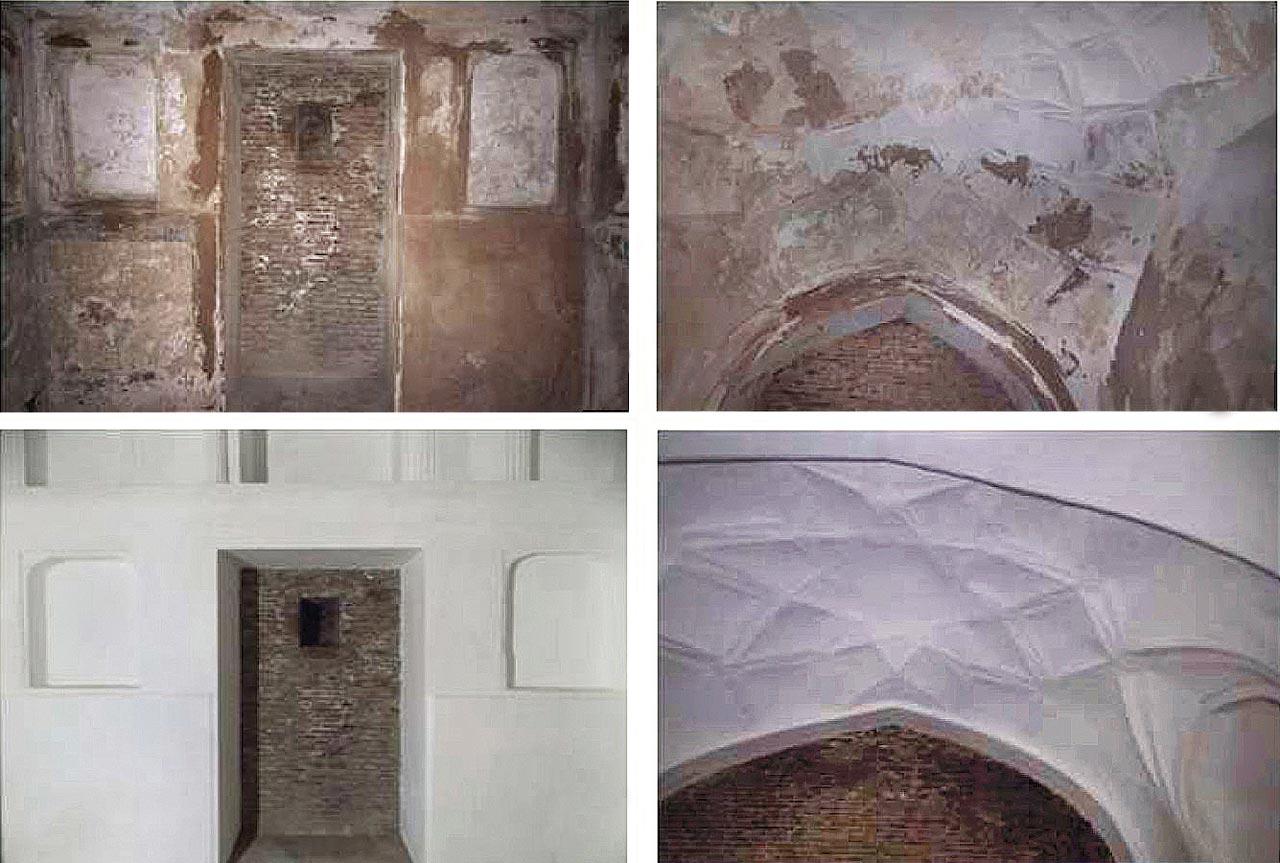

The structure before restoration. Pics courtesy/ASI

The structure before restoration. Pics courtesy/ASI

“I think it was in the 1980s that I first became aware of PN Oak and his far-fetched theories about St Peter’s Basilica, Notre Dame, Kaaba and Taj Mahal being temples,” says Safvi. “He even wrote a book titled The Taj Mahal was a Rajput Palace. Nobody took him seriously. His theories were debunked, and that was that. But in the last decade, with the growth of social media and WhatsApp, where there is hardly any verification of historical sources, his story about the Taj Mahal being Tejo Mahalaya has been picked up and circulated widely. Plus, the atmosphere at the moment is such that the Mughals are a bad word, and people are very happy to accept anything that is negative about them.”

This isn’t the only conspiracy theory about the Taj Mahal and its makers circulating these past few years. “Unfortunately, we have ill-informed guides who go around saying that a black Taj Mahal was supposed to be built,” says Hashmi, “somebody has even written a book about it. The guides also tell tourists that Shah Jahan had the fingers of artisans and labourers, who worked on the mausoleum, chopped off so that there couldn’t be another Taj. Does anybody ask them about the source of this information? If it takes 20 years to build such a structure, the thought that it needs to be maintained would have occurred to Shah Jahan. Who would carry out the repairs [if the artisans were maimed]? Besides, within 200 yards of the Taj’s south gate is a locality [Tajganj] inhabited by the descendants of the artisans. They continue to do stone inlay work and some have won the President’s medal.”

A newsletter released by the Archaeological Survey of India earlier in May contained pictures of the maintenance work they undertook on the underground cells by the riverside. These pictures should have put rumous to rest about the “locked rooms”. The decayed and disintegrated lime plaster was removed and replaced by a new one, using a traditional process

A newsletter released by the Archaeological Survey of India earlier in May contained pictures of the maintenance work they undertook on the underground cells by the riverside. These pictures should have put rumous to rest about the “locked rooms”. The decayed and disintegrated lime plaster was removed and replaced by a new one, using a traditional process

It is important to note that many of these artisans also built the Red Fort, says Safvi, adding, “The chief architect, Ustad Ahmad Lahori, also laid the foundations of the Red Fort. Another theory questions the love shared by the royal couple because Mumtaz died giving birth to their 14th child. People forget that in those days, everybody had several children. Shah Jahan had many wives but his devotion to her is recorded at various points of his rule.” Hashmi adds, “They were inseparable. She would accompany him everywhere; that’s why she was in Burhanpur. Shah Jahan had gone to the Deccan to fight and put down a rebellion.”

About the black Taj Mahal, Baig quotes her book, “Across the river was Mehtab Bagh, which has a classical char bagh, with proportions similar in the scale to the Taj Mahal. This naturally fuelled the myth of a black Taj—a twin across the river—a tomb the emperor intended for himself, perhaps perpetuated by folklore… inspired by viewing the Taj in the black reflecting pools at Mehtab Bagh on a moonlit night… Fortunately… recent excavations have revealed the true intentions of Mehtab Bagh—a critical component of the Taj Mahal Complex and one that weaves an even more powerful narrative than the idea of the Black Taj… Mehtab Bagh’s riverfront terrace has a large octagonal pool at its centre which, on a full-moon night, perfectly reflects the Taj Mahal. In this octagonal pool, measuring 88 feet across, with scalloped edges and 25 fountains, would the reflection of the Taj Mahal ripple in the moonlight? Would it be dark and brooding or shimmering white, the reflection ephemeral and even more symbolic of the emperor’s intent?”

When asked about the ongoing comments, Baig shares some food for thought: “Whether it is the Taj or Bibi Ka Maqbara [in Aurangabad, Maharashtra], thousands of Indians come and venerate these graves, irrespective of their religion. For me, it is the beauty and the perfection of the monument, but for so many, it is the reverence of our forefathers and that drives the culture in India. [Besides] we can either behave like Aurangzeb, and decide to erase history. Or, we can accept that we are the product of a multi-layered culture and look ahead. If the roadmap is to behave like Aurangzeb, then why vilify him when we are no different?”

22

No. of ‘rooms’ below the foundation. Historians say this is more like an arched corridor with doors

1980

Year the rooms were shut for public access to protect the monument after the Yamuna flooded old Delhi in 1978

17.5

The depth of the foundation for the Taj in metres

Rana Safvi recommends that you read

. Taj Mahal - The Illumined Tomb by WE Begley and ZA Desai

. Taj Mahal: Multiple Narratives by Amita Baig and Rahul Mehrotra

. Immortal Taj Mahal, the evolution of the tomb in Mughal architecture by R Nath

. The Complete Taj Mahal by Ebba Koch

. Taj Mahal by Giles Tillotson

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!