Everyone wants to live in the beach state; and many did move there. But it’s not all feni and siestas. Here’s a survival checklist from those who have called it home for a while

Representative Image

Ask any person their ideal place to settle down and eight times out of 10, it’s Goa. India’s tiny beach state has long been the perfect getaway, especially for those tired of existing in a constant state of rush.

As Katharina Poggendorf-Kakar wrote in her book Moving to Goa 10 years ago, “We had no desire to move back to a polluted metropolis with traffic snarls, aggressive drivers and an infrastructure constantly teetering on the brink of collapse.” And so many of them rushed to the state in droves during the pandemic—writers, businesspeople, professionals and families all packed their bags in search of the ideal Goan life, but did not find the endless coconut-pani-on-beach dream.

“There is no ideal Goan life...” says Heta Pandit, founder of Goa Heritage Action group and author of 11 books on Goa, one of them ironically titled, There’s more to life than a house in Goa, “...except the one you have created yourself. Sometimes, the idea of Goa is in your head.” A pioneer of sorts, Pandit moved away from Mumbai due to an accident in 1994, and has stayed in several places across Goa over the past 28 years.

Deepti Dadlani, who’s been staying in Goa for two-and-a-half years, says Goa is beautiful to live in but needs adjustment to adapt to the slowness of life

Life in Goa, many such pioneers found, comes with its own challenges. Getting around, for instance, is the major challenge. While traffic is an issue in Mumbai or Bengaluru, here, the challenge is how to get from one place to another. “One of the first things I had to do was to buy a car and learn to drive,” says Pallavi Naidu, who shifted to Porvorim from Mumbai in 2021 and handles the digital publication Alcobuzz.

Another challenge is round-the-clock Internet connectivity. Power cuts, which are frequent, shut down all connections. Naidu says she installed inverters to deal with the power cuts. Kirana stores and stationery shops remain elusive if one is in the interiors; she says that when she used to live in Siolim, she had to drive every morning for 5-10 minutes to get bread and eggs. Plumbers, carpenters, and workmen are hard to find and slow to respond—a fact that’s earned locals an unenviable reputation. “I remember the first time I called a plumber. He came after four days,” says Nolan Mascarenhas, a financial analyst and food writer. “In Mumbai, he’d come in 15 minutes.”

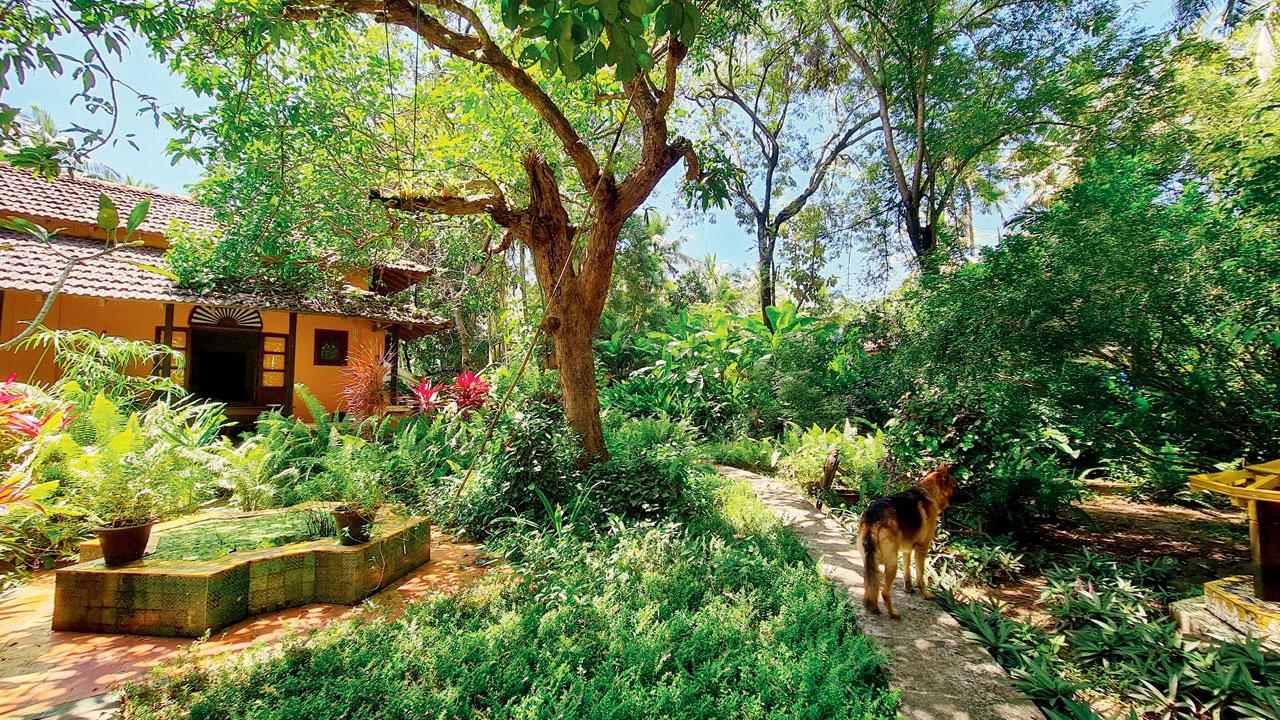

Katharina Poggendorf-Kakar, author of Moving to Goa, planted her garden in Benaulim herself. Gardening keeps her rooted to her identity

Katharina Poggendorf-Kakar, author of Moving to Goa, planted her garden in Benaulim herself. Gardening keeps her rooted to her identity

Coming to which, “Susegad means contentment and the art of living. It’s not laziness,” corrects Mascarenhas, who moved to Vagator in 2012 to get in touch with his roots. The 39-year-old says it’s necessary to lower expectations when moving to Goa; it’s not the endless rave that films will have you believe. He says this stereotyping of the Goan lazing around on the beach, beer bottle in hand, has limited the discovery of the state’s true cultural identity. However, even he agrees that the passage of time in Goa is deceptive. “It would take me four hours to do a task in Mumbai, while in Goa it would take five or six days.”

The slowness of life afflicts the metro resident in the initiation period almost like a malady. Naidu recalls how, during her first six months in Goa, she would go to the beach every single day. It took her nearly a year to adjust to how time works in Goa.

It was the same for hospitality brand strategist Deepti Dadlani, 41, who has been staying in Siolim for two-and-a-half years. For Dadlani, the cramped spaces of the city didn’t suit her physiologically, thus the intense need to work on the beach. She quickly found it “too casual to do any structured work”. “Slowly and steadily, you realise you are going to the beach too much,” says Dadlani. “You may be living in Goa, but you have to work office hours. And you can’t take a beach break in the middle of them.”

Katharina and her husband, writer and psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar, have lived in Goa for 20 years now

Dadlani adds that if you’re not equipped to build a life alone, as an adult, the transition will be harder. “Make sure that you have structure in your life,” she advises. “Look for a home that is close to resources that are important to you. My advice would be to treat Goa how you would treat Mumbai. Don’t come in trying to stay near the beach.”

Pandit says she wouldn’t describe life as slow-paced. “It’s just an opportunity to pace it the way you want—you can live slow or fast. You can work from home or have a routine.” She adds, “There’s always some campaign that we are running. Letters to be sent out, people to be reached and convinced. There are meetings to attend and festivals to be organised at times.”

For those hoping to buy their own home, Kakar says that it is important to know where one’s dreams fit in with practicalities. “I think one should move here,” she says, “rent first, explore and figure out which part of Goa you like and want to settle down in.”

Heta Pandit, Nolan Mascarenhas and Pallavi Naidu

However, those who’ve been in the beach state for a while agree unanimously how peaceful life is. The state, they gush, frees their mind and gives them space to think. “For me, the most important part is being grounded and connected to a variety of natural elements,” says Kakar.

“I think I’ve become calmer, more rooted.” It comes from her garden, which she planted herself. She works in her garden for an hour every morning, digging around and enjoying the scents of the soil. For Mascarenhas, it comes from the green of the paddy fields around his ancestral home. For Pandit, an environmentalist, it’s the beauty of the state’s heritage and local ecology.

“I think people who come here need to adjust to the place, rather than expecting the place to adjust to them,” are Dadlani’s words of wisdom. Pandit has similar views. “Goa is not a use-and-throw place. Learn to love its environment, its biodiversity, heritage, ecology, its problems and roll up those sleeves and pitch in. Once you have done that, you can think about heading to the beach!”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!