Climate-tech is emerging as one of the largest sectors for private capital flow, and Mumbai and its surrounding metros are turning into a hotbed for green businesses

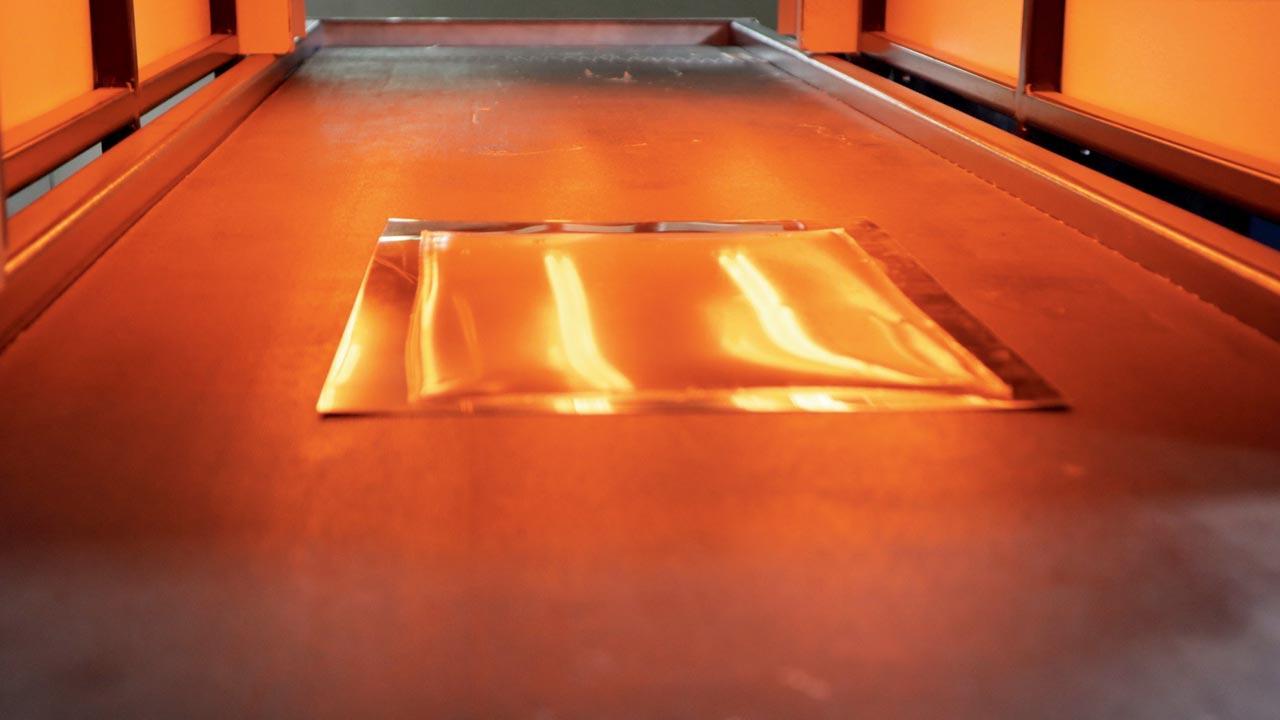

Zerocircle, a city-based startup with a lab in Pune, makes packaging for food, disposable bags and bottles from marine water macro-algae. (Above) A seaweed flexible film seen at the final processing stage before going into a roller. Pic/M Fahim

If Google hadn’t hired Neha Jain during an on-campus placement drive, she would have been a journalist. The Mumbai-based entrepreneur, who is a journalism graduate from Christ College, Bengaluru, admits that life had other plans. After working in product development and marketing with the tech giant, Jain went on to launch the country’s first, late-night delivery service, Fly By Knight, in Mumbai in 2011. “This was pre-Dunzo and Uber. It was meant to be an on-demand service for anything one needed in the after-hours. But, while we did well, I think it was a little too ahead of its time,” feels Jain, who decided to return to corporate life. It’s then that she got to work on a CSR project, which involved helping a tyre manufacturing company reduce its carbon footprint. “We started mapping all the stakeholders involved in the journey of the tyre from after use to the landfill, and then a recycling centre. During the same research, I was able to understand the problem with recycling plastic as well, and why certain materials got rejected [for recycling].” Jain took this on as a personal project: For eight months, she didn’t let out any flexible plastic—product or packaging made primarily from unmoulded plastic, like plastic bags, films, wraps, pouches or laminates—from her home. “It came to a point where I was running out of space... And back in 2018, barely anyone was taking flexible plastics [for recycling].”

Soni seen conducting geophysical and UAV-based prospecting for groundwater exploration at Banda, Uttar Pradesh

Soni seen conducting geophysical and UAV-based prospecting for groundwater exploration at Banda, Uttar Pradesh

Convinced about finding a sustainable solution, the 36-year-old spent the next few years putting together a research and development team, which now works out of Pashan in Pune, to look into greener alternatives. Her startup, Zerocircle, that was born in the thick of the pandemic, manufactures ocean-safe materials made from locally cultivated and sustainably-sourced seaweed. “Seaweed is a macro algae that grows in marine water, and we have enough of it around us. It can also scale well, if we do ocean farming. Another beautiful quality is that it absorbs CO2 much faster than any land-based plant or tree. Certain seaweed species grow up to two metres a day, so the faster it grows, the faster it absorbs CO2 and reduces acidity in the ocean.” The products made by Zerocircle include safe-for-food-contact packaging, disposable bags and bottles, many of which are otherwise made using petroleum-based sources. These seaweed-based products dissolve in the ocean in a matter of two to four hours depending on the temperature of the water (in boiling hot water, it can disappear in seconds)—it takes the ocean 450 years to break down the plastic—causing no harm to the marine ecosystem, thus, mitigating the environmental impact.

Farmers send their Google location via WhatsApp. Based on this data, the team investigates whether or not the farm has groundwater source

Farmers send their Google location via WhatsApp. Based on this data, the team investigates whether or not the farm has groundwater source

Jain’s startup is among the green and sustainable businesses taking centre-stage in Maharashtra. The pandemic has only bolstered the shift with climate-tech emerging as one of the largest sectors with private capital flowing into it, says Jui Joshi, partner at Climate Collective Foundation, a support platform focused on empowering entrepreneurs throughout South Asia by building, or strengthening, local climate startup ecosystems. Led by Pratap and Pramod Raju, Joshi and Nalin Agarwal, the non-profit since its launch in 2016, has extended support to over 720+ startups. Of the total climate startups they support, 21 per cent are from the state. “Maharashtra has the potential [to emerge as a strong market for green startups], especially with Mumbai being the financial capital. That the state is home to institutions like NEERI [National Environmental Engineering Research Institute] and IIT Bombay [Indian Institute of Technology Bombay] means that there’s scope for strong technology-driven businesses. It definitely has a good enabling eco-system for any business to survive. And while the response has been a bit mixed here, when you look at the pan-India landscape, Maharashtra has some of the better startups, which are technology-oriented and offer quality solutions,” thinks Joshi.

Among the green-tech startups leading the race, says Joshi, is Riddhish Soni’s Aumsat Technologies LLP, which is incubated with VJTI, Matunga, IIT-B and College of Engineering Pune (COEP). Before starting Aumsat, Soni was working as a scientist with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). Part of the Chandrayaan-2 Mission to send an orbiter, lander, and rover to the moon, Soni says he was privy to “two Indias”. “One India had reached the Moon and Mars, while the other was struggling to meet day-to-day needs and [achieve] a decent livelihood,” he tells us over a telephonic chat. Soni realised that often the research that scientists like him did, got locked as statistics in libraries. “I felt that there was a need for someone to use this knowledge to create technology that could serve larger beneficiaries at the grassroots level, especially marginalised famers.”

Former ISRO scientist Riddhish Soni launched Aumsat Technologies LLP, a few months before the pandemic. They use radar satellites to trace groundwater and its flow, and detect microplastic contamination over open water bodies. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Former ISRO scientist Riddhish Soni launched Aumsat Technologies LLP, a few months before the pandemic. They use radar satellites to trace groundwater and its flow, and detect microplastic contamination over open water bodies. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

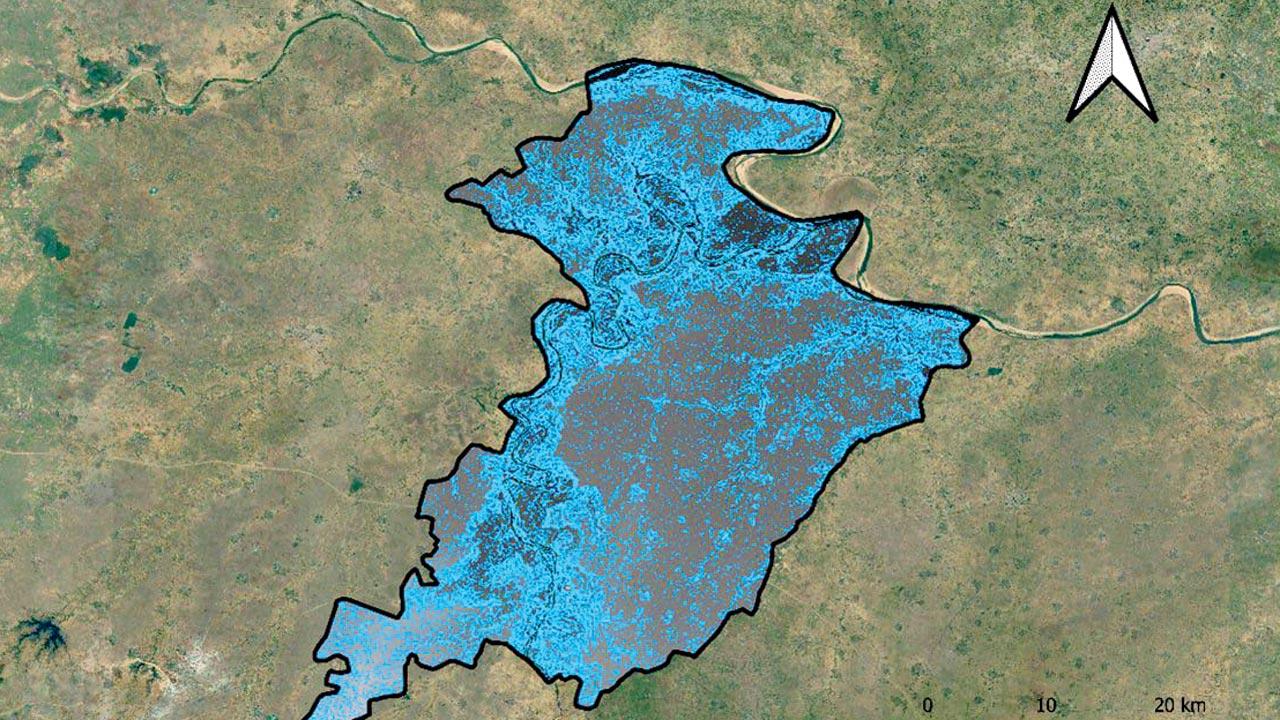

At the fag end of 2019, Soni quit his job at ISRO to start Aumsat, which uses radar satellites to trace groundwater and its flow. “Without groundwater, there can be no agriculture in India, because 80 per cent of our farmers depend on it for irrigation. So, we pivoted the technology we used for Chandrayaan—to find traces of titanium, helium, minerals and water on the moon—to discover underground resources for farmers,” says the 30-year-old CEO. Satellite derived radar observations is not just used to trace sources of groundwater, but also the level of ground displacement changes caused as a result of overexploitation of water resources.

Jui Joshi and Karishma Shah

Jui Joshi and Karishma Shah

The team currently uses an affiliate-marketing model, working with irrigation departments, government-run institutions, farmer producer organisations (FPOs), and non-profits, who then connect with farmers. Since its launch two-and-a-half years ago, it has been working with 3,200+ farmers. Climate Collective’s mentorship aided this journey. “What we require from the farmers is their Google location, which can be sent to us via WhatsApp. Based on that, we tell them whether they have a groundwater source in their farm or not.”

The PadCare bin designed by Pune-based PadCare Labs can store 75 pads for up to four weeks without any bacterial contamination or odour in the washroom. The pads are brought to a nearby PadCare facility and processed to make them fit for recycling

The PadCare bin designed by Pune-based PadCare Labs can store 75 pads for up to four weeks without any bacterial contamination or odour in the washroom. The pads are brought to a nearby PadCare facility and processed to make them fit for recycling

One of the recent projects they collaborated on was in Banda district of Uttar Pradesh, which is home to eight lakh farmers. “We also helped them detect paleo channels, which are buried streams and river channels not known, but flowing underground.” His team also worked with an organisation in Tamil Nadu, which collects excess water from rain water harvesting. “We helped them identify fissures and cracks underground, and pump this excess water inside so that it can be used by future generations.” The team has started operations in the drought-affected Vidarbha region, which continues to record the highest number of farmer suicides in the state—of the 2,489 farmer suicides reported between January 1 and November 30, 2021, over 50 per cent were from here.

(From left) Purav Desai, Rahul Batra, and Lokesh Sambhwani, founders of Refillable, a zero-waste refill service, which creates smart packaging and refill systems to eradicate waste at source for brands and consumers

(From left) Purav Desai, Rahul Batra, and Lokesh Sambhwani, founders of Refillable, a zero-waste refill service, which creates smart packaging and refill systems to eradicate waste at source for brands and consumers

Apart from tracing and replenishing groundwater, Aumsat also provides satellite-based analytics for detecting microplastic contamination over open water bodies. Unlike conventional costly and time-consuming sample collection and IoT-based point measurement methods used in open water quality monitoring, their services detect microplastic concentration without physically being present on the field.

Meanwhile, a bunch of 20-somethings from Mumbai, launched Refillable, a zero-waste refill service, which creates smart packaging and refill systems to eradicate waste at source for brands and consumers. Started by Lokesh Sambhwani, 25, Purav Desai, 25, and Rahul Batra, 28, Refillable took off during the COVID-induced lockdown. “We believe you pay for the product and not for the packaging... just like the milkman service we used to have in the olden days,” says Sambhwani. Currently, the startup offers homecare liquids, which includes dishwasher and laundry detergents, toilet and floor cleaners and handwash, on its online store, but it hopes to expand to selling groceries and other essentials. The team has a network of refill bikes and trucks across Mumbai and Bengaluru. “They come to your doorstep, and you can refill the product of your choice in the volume of your liking.” The deliveries usually take anywhere about 40 to 72 hours. The team has also installed refill machines in communities, retail stores and societies.

The idea for the initiative, says Sambhwani, came to them in 2018, when the government was contemplating a ban on single-use plastics. “Unfortunately, due to the lack of alternatives available, there was a lot of greenwashing in the industry,” he says. Sambhwani and his team started by launching Cupable, which encouraged the use of recyclable and reusable cups. “This followed the same principle as Refillable, except that it was aimed at eliminating single-use packaging for the food and beverage industry. In our first year of operations, we saved more than 2 million single-use plastic cups from entering the landfill.”

Neha Jain, a former Google employee, decided to get into algae entrepreneurship, as she was looking for sustainable solutions to the plastic problem

Neha Jain, a former Google employee, decided to get into algae entrepreneurship, as she was looking for sustainable solutions to the plastic problem

Refillable was launched in Mumbai in May 2021. “We started with housing societies where wet and dry waste segregation was already happening—they are a bit more environmentally-conscious and understood the intent of our work. But the word spread faster [than we expected]. Today, we cater to over 2,000 households.”

Seaweed grows in marine water. According to Jain, it absorbs CO2 faster than any land-based plant or tree. “Certain seaweed species grow up to two metres a day; the faster it grows, the faster it absorbs CO2 and reduces acidity in the ocean”

Seaweed grows in marine water. According to Jain, it absorbs CO2 faster than any land-based plant or tree. “Certain seaweed species grow up to two metres a day; the faster it grows, the faster it absorbs CO2 and reduces acidity in the ocean”

Joshi of Climate Collective Foundation says the need of the hour is to have government policies that support climate-tech ecosystems to survive. Earlier last month, Manisha Verma, the principal secretary for skills, employment, entrepreneurship and innovation department had announced a R200-crore fund to invest in deep tech startups. “It’s a strong signal,” she says. Similar initiatives for climate-tech projects will boost the confidence of the emerging startup industry. “Once an early-stage startup gets a pilot with the government, it gives them tremendous visibility and validation for their technology, and helps them commercialise faster.” Joshi feels that even corporates need to get serious about sustainability. Jain’s Zerocircle, for instance, received a vote of confidence from a global food brand, becoming the first startup that the brand incubated in India. “Corporates need to re-evaluate their supply chain, and find out where they need innovative technologies coming in. That way, they can reach out to the right startups and make sure the right innovation is plugged in,” adds Joshi.

At Zerocircle’s laboratory in Pashan, Pune, the team has been using dry seaweed to make safe food contact packaging and disposable bags. These seaweed-based products dissolve in the ocean in a matter of hours. Pics/M Fahim

At Zerocircle’s laboratory in Pashan, Pune, the team has been using dry seaweed to make safe food contact packaging and disposable bags. These seaweed-based products dissolve in the ocean in a matter of hours. Pics/M Fahim

As lead of the Women in Climate Entrepreneurship Initiative at the Climate Collective, Joshi says that the climate discourse also needs a gendered focus. “Climate is a complex problem; unless we get diverse perspectives, we are never going to be able to find holistic solutions,” she argues, explaining, “Climate is not just reducing greenhouse gas emissions, it’s also adapting to changes, and building resilient societies to mitigate the effects of global warming. We need to reach out to those experiencing these effects, especially people who are closely linked to natural resources—in most cases, it’s women.” Currently, 30 per cent of the startups that Climate Collective supports are led by women.

The lack of hygienic disposal facilities for sanitary pads, is what led Aasawari Kane to join Pune-based PadCare Labs, founded by Ajinkya Dhariya. Her startup zeal kicked off around five years ago, when she moved from Mumbai to Pune to pursue a Masters degree. Finding an incinerator in her hostel, Kane remembers attempting to switch it on after disposing her sanitary pad, only to see smoke emanating in the corridor. “That stayed with me. After completing my Masters, I heard that Ajinkya was starting an initiative for safe disposal of pads. I decided to join him,” says Kane, who is founding member. The PadCare bin designed by their startup comes along with a PadCare vap—secured Collection bins which can store 75 pads for up to four weeks without any bacterial contamination or odour in the washroom. The pads from the bins are brought to the nearby PadCare facility and processed to make them fit for recycling. These bins have been placed at airports, hotels, corporate offices and educational institutions across Pune, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Delhi.

Karishma Shah is the CEO and co-founder of EnvoProtect, which is a Pune-based solid waste management startup that converts solid waste emerging out of recycled paper mills into climate-conscious products that can be used for heating applications. Shah claims that the manufacturing industry is still not ready for women in a leadership role. “That makes the challenge interesting,” she says. “But I can say that women in the manufacturing industry set the right processes, structure, and the right teamwork needed for manufacturing processes.” She cites a personal example. “We do a manual sorting process [of solid waste] in our factory, and have both men and women engaged in the task. What I noticed is that while one man would sort 100 kg per hour, a woman would sort 250-300 kg per hour. That’s the speed I wanted from one person. I observed this for 10 days, and noticed that at no given point, did the women slack. They were determined and focussed.” Shah says that women also impact green decisions. “The women working at my factory went back home, and stopped using plastic; they even discouraged other members in the household from doing so.” It’s what makes them important stakeholders. “They are part of the solution.”

450

Approximate no. of years it takes the ocean to break down regular plastic

2-4

No. of hours it takes for seaweed film to disintegrate in water

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!