Unfettered by time, the goddess is a terrifying destroyer to some, and a family member to others. Who’s then to decide what Kaali thinks and drinks?

A member of the Navi Mumbai Bengali Association’s Kaali Mata temple in Vashi Sector 6 during Friday evening puja. Pic/Sameer Markande

Politician Mahua Moitra’s contention has been this: Her [version of] Goddess Kaali eats meat and accepts alcohol. The TMC (Trinamool Congress) MP was duelling those criticising a film poster of the goddess, which showed her smoking. Moitra has a point: Not just this particular goddess, but all of Hinduism has as many interpretations and versions of the gods as the number of deities themselves. This make-it-up-as-you-go-along and a-god-by-any-other-name… theism is the crucial difference between Hinduism and monotheistic Abrahamic religions.

ADVERTISEMENT

And if any god were to take to tobacco, it would most likely be Maa Kaali—a primal, ruthless, raging, killing force. Her tongue drips blood, she wears a girdle of human arms and her open hair whips about in the winds of time. She holds the khatvanga or skull-topped staff in her hand and is ready for war. Her name literally gives away the colour of her skin, and she is connected to Shiva’s Mahakaal version, the one who is beyond time and death. A far cry from the beatific, smiling Goddess Durga, from whom she is said to have sprung.

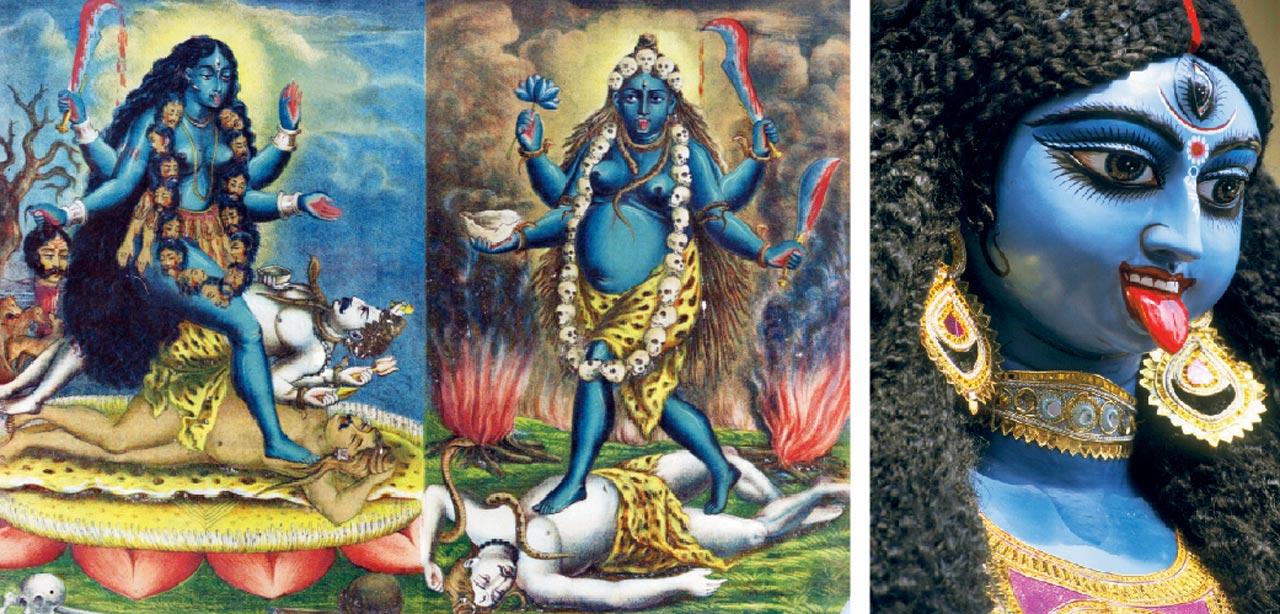

An artistic impression of Kaali dating back to 1885-90, and a modern interpretation of the goddess as seen in Kolkata’s pandals. Theologists say that somewhere in the 17th century, she lost her blood shot eyes, belly, and developed a gentler face and body, rehabilitated into the mainstream. Pics/Getty Images

An artistic impression of Kaali dating back to 1885-90, and a modern interpretation of the goddess as seen in Kolkata’s pandals. Theologists say that somewhere in the 17th century, she lost her blood shot eyes, belly, and developed a gentler face and body, rehabilitated into the mainstream. Pics/Getty Images

“As per [the text] Devi Mahatmya,” explains Joy Chakraborty, Honorary Advisor to the Bengal Club at Shivaji Park, which houses a Kaali temple, “she is also known as Kalika, and is believed to have originated from the forehead of Maa Durga and is her angry manifestation. She defeats the demons Chanda and Munda, and also Raktabija. However, her bloodlust does not stop and she continues to kill, endangering creation. Lord Shiva, her consort, lies down in her path and when she steps on

him, she snaps out of her rage and is pacified.”

What Chakraborty is referencing is the difference between Parvati and Kaali. The former mellows his destructive character; the latter provokes it.

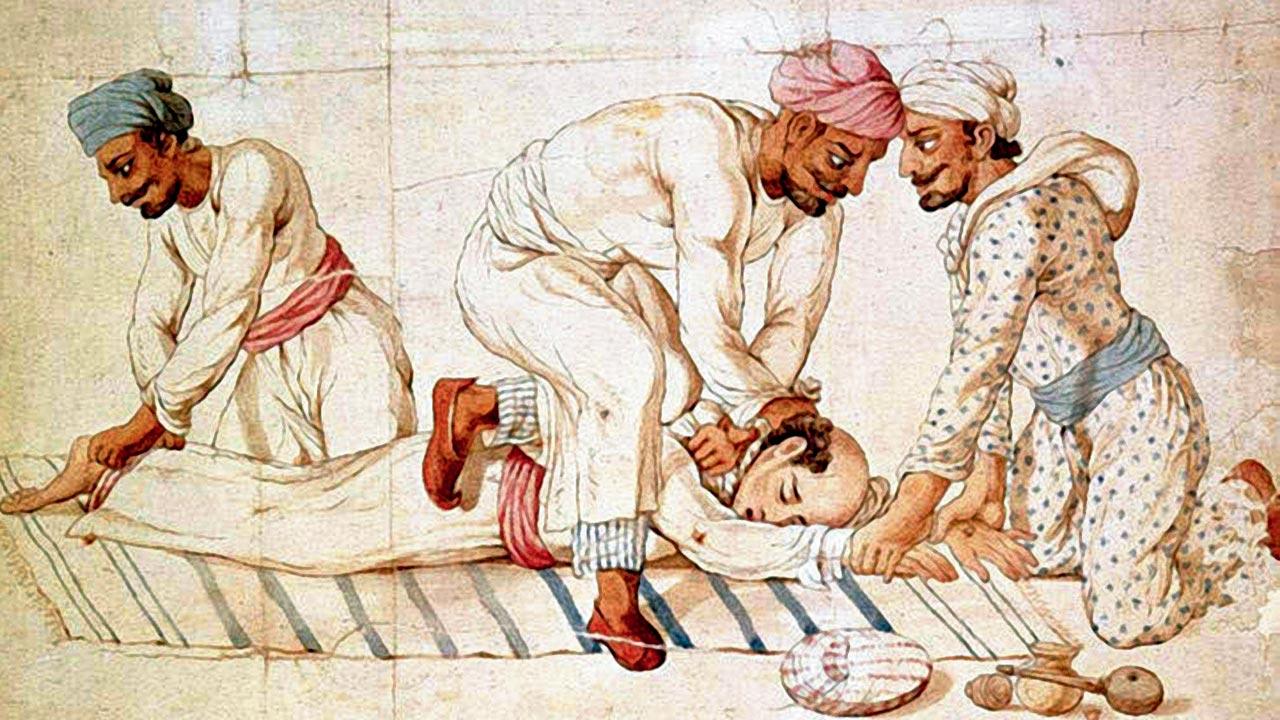

Thugs in the act of strangling a traveller, as depicted by Frances Eden in 1838. These were believed to be members of a sect of servitors of Kaali. The British are said to have come down heavily on this sect. Pic/Getty Images

Thugs in the act of strangling a traveller, as depicted by Frances Eden in 1838. These were believed to be members of a sect of servitors of Kaali. The British are said to have come down heavily on this sect. Pic/Getty Images

Swami Satyadevananda, the Adhyaksha (secretary) of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission in Khar, tells a similar story. “Kaali is mentioned in the Saptshati [a text from the Markandeya Purana describing Durga]. The devas and asuras fight over svarg or heaven, and the former are defeated. The asuras occupy svarg, and the king of devas, Indra, beseeches the holy trinity—Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva—to help them. They create a primordial female force—Durga—to drive the asuras out of paradise.” Durga, though a warrior goddess, is seen as an avatar of Parvati, and a manifestation of the primal female energy, Shakti. “She goes on a killing spree through many kalpas [eons that mark the creation and dissolution of the universe],” he says, “becoming a terrifying being. She wears no clothes, has blood all over her body and is tearing creatures apart with her bare hands.” This blood rage links Kaali to Tantra and black magic. Tantric teachings are a collection of ancient magical stories and folk practices. But from the Ramakrishna Mission, the story ends on a more benevolent note. “Horrified, all the gods beseech her to come back to her Durga avatar,” says Swami. “‘You are our mother,’ they say, ‘children should not be terrified of their mother.’ And she does, while promising them that she will become Kaali whenever they need her to.” This unforgiving brutality is what makes her a force to be feared and admired (which holds true for all mothers).

A few hundred years ago, an unmarked, unblemished Brahmin boy would be sacrificed to appease her, says the Swami. Later, this gave way to buffaloes and goats, and in the Ramakrishna Math, they offer Maa Kaali a symbolic sacrifice of bottle gourd and sugarcane. “Ramakrishna Paramhansa [guru to Swami Vivekananda, who named the order after him], worshipped Maa in Dakshineswar temple in Kolkata, under the patronage of Rani Rasmani,” says the Swami, “he stopped the sacrifice of living creatures.” Ramakrishna considered himself Maa Kaali’s child and believed she acted through him. The Interpretation of the Mission is that both the devas and asuras are within each of us, fighting every day. We pray to Kaali to help defeat the asuras and lean towards our deva nature. Kaali’s origins, believe many theologists, lie in tribal lore.

Joy Chakraborty, Honorary Advisor to the Bengal Club at Shivaji Park, which houses a Kaali temple, says that Kaali defeats demons Chanda and Munda, and also Raktabija. However, her bloodlust does not stop and she continues to kill, endangering creation. “Lord Shiva, her consort, lies down in her path and when she steps on him, she snaps out of her rage and is pacified”

Joy Chakraborty, Honorary Advisor to the Bengal Club at Shivaji Park, which houses a Kaali temple, says that Kaali defeats demons Chanda and Munda, and also Raktabija. However, her bloodlust does not stop and she continues to kill, endangering creation. “Lord Shiva, her consort, lies down in her path and when she steps on him, she snaps out of her rage and is pacified”

“The Jaiminya Brahmana dated around the 8th century BC tells the story of one Dirgha-jihvi or ‘the long-tongued one’,” wrote mythologist Devdutt Pattnaik in his weekly column in this newspaper. “It is speculated that Dirgha-jihvi refers to Kali-like goddesses worshipped by agricultural communities, who were probably matriarchal. A century or two after the Jaiminya Brahmana, the Vedic priests put together the Mundaka Upanishad where Kali is one of the seven quivering tongues of the fire god, Agni, whose flames devour sacrificial oblations and transmit them to the gods. Between the 2nd century BC and 3rd century AD, Kali appears for the first time as a goddess in the Kathaka Grhya sutra, a ritualistic text. In the Devi Mahatmya, dated roughly to 8th century AD, Kali became a defender against demonic and malevolent forces and by the 19th century, she is a goddess in the mainstream pantheon, a symbol of divine rage, of raw power and the wild potency of nature. The one who was once feared as an outsider had made her way right to the heart of the mainstream.”

Now, she is motherly, with dramatic doe eyes and of blue complexion.

Devotees pray at the Kashi Aai or Kaali Mata temple in Thane East last Friday. Pic/Sameer Markande

Devotees pray at the Kashi Aai or Kaali Mata temple in Thane East last Friday. Pic/Sameer Markande

The widely accepted lore about her is that the devas called on her to kill the demon Raktabij, who had been granted a boon that he could not be killed by any man. From every drop of Raktabij’s blood as he battled the gods, sprung a hundred more demons. Kaali lapped up his blood before it touched the ground and ate up his clones. When the colonists discovered this mother goddess, they could not reconcile to a female divinity, let alone one that was unclothed, wild and terrifying. In image, the closest reference they had was that of the devil who drank blood. “In 19th century Orientalist fiction, she became the goddess of thugs and murderers who demanded blood sacrifice. Indian freedom fighters saw her as Mother

India stripped of her glory!” writes Pattnaik.

Twentieth century feminists made her a symbol of liberation, seeing her nakedness as defiance and subversion. Another story about Kaali is found in the Linga Purana (500 to 1000 CE). “Shiva asks his wife Parvati to defeat the demon Daruka, whom only a woman could kill. Parvati merges with Shiva, reappears as Kaali and does the deed,” writes Linda Heaphy in her online piece. “The Vamana Purana (900–1100 CE) has a different version. When Shiva addresses Parvati as ‘Kali, the black one’, she is affronted and performs certain austerities to lose her dark complexion, generating Kali as a separate entity.”

Kaali pujan is most auspicious on two occasions—the first amavasya (new moon) after Durga Puja, when Kaali is supposed to be at her pitiless worst, and the moment when Ashtami turns into Navami during pujo. “We believe that this is the moment Maa Kaali, as Chandi, killed the demon,” says Swami. “It’s called Sandhi pooja and this would be the precise moment of sacrifice in the olden days.” “Devotees observe a strict fast, leaving out even water,” adds Chakraborty. “The hibiscus flower is Maa Kaali’s favourite, and is offered to her.” The Goddess is most worshipped in Kashmir, Bengal and Kerala.

In Bengal, Moitra’s home state, Kaali becomes a personal goddess—a mother to a devotee or the daughter of a household. Professor Aveek Majumdar from the Department of Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University cites the examples of the works of Shakto poets Ramprasad Sen and Kamalakanta Bhattacharya, whose verse speak to Kaali as a family familiar. Written in the18th century, these songs are popular even today and part of the state’s cultural heritage. One of the songs translates to the devotee as a child, saying to his mother: I will eat you up/ I will take away your garland of skulls and make it part of my cooking…’ Another one by Kamalakanta says, “Is my mother really black? /If she’s black/ How can She light up the world?” These songs were later sung by Ramkrishna Paramhansa.

“Maa Kaali has been worshipped more than Durga,” he says, “and the relationship with her is personal. She’s a symbol of victory over evil, but you can also tell her your day-to-day troubles, debate and argue with her, even speak to her angrily or petulantly. She’s a household entity, the governing force of everyday life. You have to look at her from within, not view her from the outside like a distant god.”

Bengal has a long cultural history of forging close, familial relationships with divinity. Rabindranath Tagore has described god as his ‘bondhu, sakha’ friend and companion. “Kaali is worshipped by everybody, the rural and the downtrodden; in Tantra, there are 10 forms of Kaali, each with a specific tenet and is worshipped accordingly. There are different Kaalis in different areas. There is also a Shamshan Kaali worshipped in crematoriums; she is Mahakali, the counterpart of Mahakal or Shiva, connected with life and death” explains Prof Majumdar. “So there’s no central way of worshipping her. It differs from person to person, and even sect to sect with Tantra. In the rural areas, fish and goat meat is offered to her, while it is vegetables and fruits in other areas. Alcohol is offered by some sects, and distributed as prasad to the devotees,” he adds.

There is a legend of a group of men sacrificing a young Brahmin of character to appease Kaali. Unimpressed, she goes on to kill her worshippers and drink their blood, refusing to bow to their image of her, their ignorance and lack of understanding of who she is.

Devoted to large scale homicide, especially of those who try to control her, could taking a drag be held against the Goddess? Even as the worship of her male counterpart, Shiva, is so strongly linked to cannabis? How does an addictive habit travel to become an immoral one? Is it because the cigarette—introduced by and associated with the West—is seen as a corrupting influence? Is the addictive nature of nicotine? Or is it simply the shorthand: A smoking woman is one cocking a snook at order-driven society?

Leena Manimekalai; (right) Mahua Moitra. Pic/Getty Images

Leena Manimekalai; (right) Mahua Moitra. Pic/Getty Images

The controversy

Last week, a controversy erupted over the poster of a documentary film on goddess Kaali; it showed the actor playing the goddess smoking a cigarette. Its Sri Lankan filmmaker Leena Manimekalai came under fire on Twitter and the outrage grew after Trinamool Congress MP Mahua Moitra defended her right to artistic expression. Speaking of her own personal experience, Moitra said that “her Kaali” was “meat-eating and alcohol-accepting” and that each person has his or her unique way of offering prayers. Since then, the July 2 tweet of the poster of the film has been taken down by Twitter. A lookout notice has been filed against the Indian-Canadian filmmaker, after several FIRs were filed against her in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh for hurting religious sentiments. Several FIRs were also filed against Moitra, and the West Bengal BJP has asked the TMC to dismiss her.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!