Art curator Ranjit Hoskote’s new FN Souza show in Mumbai examines why the Modernist painter’s early years in Portuguese Goa influenced his art and preoccupation with religious orthodoxy

Ranjit Hoskote next to Souza’s Mammon (oil on canvas, 1961). Pics/Suresh Karkera

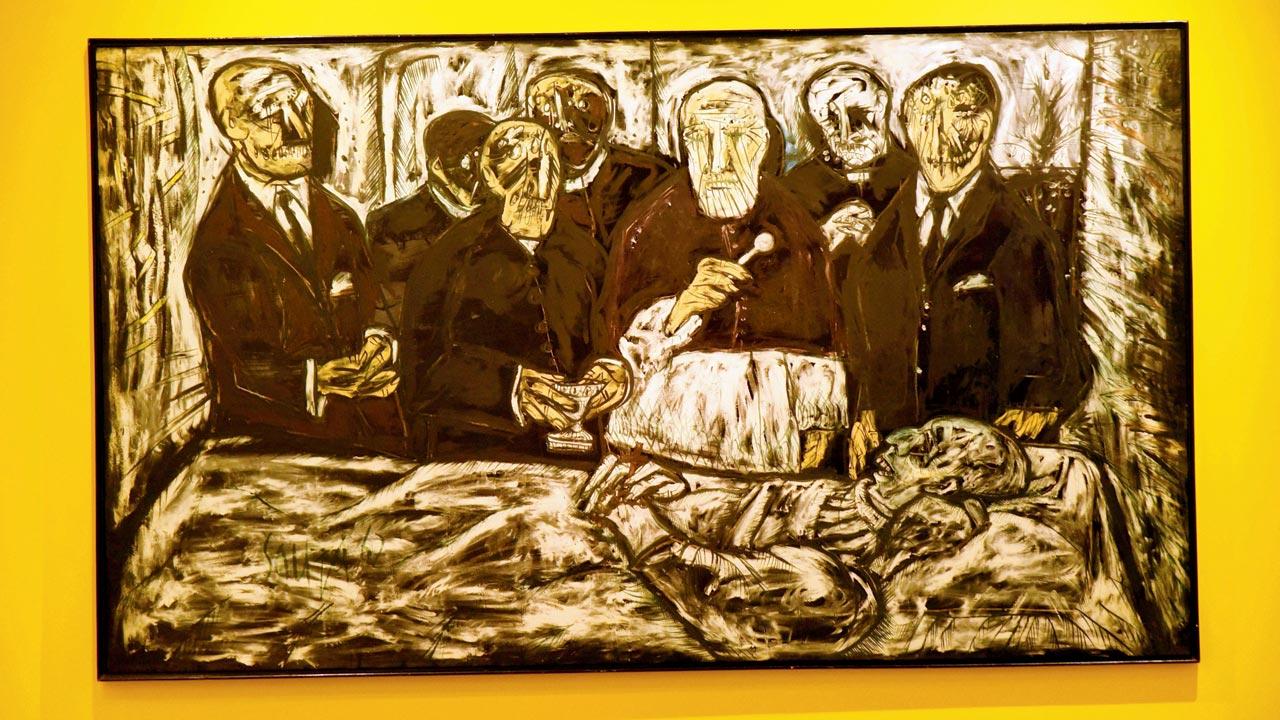

Horror. That’s the feeling Ranjit Hoskote remembers experiencing, when he first encountered Francis Newton Souza’s Death of a Pope (oil on canvas, 1962) several years ago. To him, the satirical painting, which Souza (1924-2002) reimagined from a black and white photograph of the deceased Pope Pius XII lying in state at St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican, on October 11, 1958, surrounded by his collegium of ecclesiastical mourners seemed to be a rather, “savage and cruel take on a solemn moment”. Needless to say, the painting left a deep impression on him. As a cultural theorist and curator, Hoskote kept returning to the artwork, each time he investigated Souza the artist, notorious for his appetite for provocation. It began with Aparanta: The Confluence of Contemporary Art in Goa, a landmark group exhibition that he curated in Panjim in 2007, where he turned the spotlight on Goa’s artists in their ancestral land. This was followed by a furious exercise of collecting and making notes on the peripatetic painter, somewhere in 2012. We are in 2021, when we meet Hoskote at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya, just days before the opening of With FN Souza: The Power and the Glory. The walls are still a work in progress, but Souza’s paintings have already found a pride of place here. He admits that the passage of time hardly restrained his curiosity for the painter. “It was one of my unrealised dream projects.”

Francis Newton Souza’s Death of a Pope (oil on canvas, 1962) is based on a black and white photograph of the deceased Pope Pius XII lying in state at St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican, on October 11, 1958, surrounded by his collegium of ecclesiastical mourners. In Souza’s painting, the men surrounding the Pope are shown as scarred and monstrous figures. Several of them are distorted to resemble Hitler. Pics/Suresh Karkera

Francis Newton Souza’s Death of a Pope (oil on canvas, 1962) is based on a black and white photograph of the deceased Pope Pius XII lying in state at St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican, on October 11, 1958, surrounded by his collegium of ecclesiastical mourners. In Souza’s painting, the men surrounding the Pope are shown as scarred and monstrous figures. Several of them are distorted to resemble Hitler. Pics/Suresh Karkera

It all came together when Puja Vaish, curator and artist, and the director of the JNAF approached him two years ago, to curate a show around Souza’s paintings from their collection. The proposal was lying around, he says. The ebbing of the pandemic and reopening of the museum, allowed ample leg room for the new art show, which opened on Saturday, and will be on till January 3, 2022.

The exhibition showcases 23 of the Goan painter’s artworks, 13 of which include chemical works loaned from the Pundole Family collection. Pivotal to this show is the rarely exhibited Death of a Pope. “I’ve always wanted to do a show of Souza around this incredible painting,” Hoskote shares, during our walk-through. The idea wasn’t just about developing a one-object exhibition, but also to look at this painting in particularity, and understand the roots of Souza’s preoccupation with organised religion and orthodoxy. “The problem with Souza’s reception is that he is thought of as the enfant terrible of the postcolonial Indian art scene, and an iconoclast and a bohemian soul—all of which are true, but they are not really an explanation of his art,” feels Hoskote. Neither is the fact that he was one of the six founding members (along with SH Raza, MF Husain, KH Ara, HA Gade, and SK Bakre) of the Progressive Artists’ Group in Bombay. “Yes, they were lifelong friends and colleagues, but they were not united by a single style or ideological perspective,” he adds.

Some of Souza’s works are inspired from the landscape of Saligao

Some of Souza’s works are inspired from the landscape of Saligao

Hoskote says that as an art historian, he is “usually suspicious of big paradigms”, which more often than not, are stylistically oriented or generic. “What was of interest to me was how Souza managed his lifelong chaotic connection with religious authority, and, how all of that goes back to his formative years, and childhood in Goa in the 1920s.”

Souza was born in Saligao, Goa, in April 1924, then a part of the Portuguese Empire in India. “They were tough years for him, but he was clearly resilient. He lost his father very early in life, and then had an attack of smallpox, which left him disfigured,” says Hoskote. He harks back to critic WG Archer, who in 1965 wrote how these experiences gave the artist “a sense of life as cruel, violent, and unjust. He was led to envy but also to scorn figures in authority, and his powerful father-figures—priests, elders, businessmen, patriarchs—have often a fantastic grandeur but, at the same time, features that are moronic in their senseless stupidity”.

For the show, Hoskote has juxtaposed Souza’s work with Christian Indian sacred art—images of Jesus and Mary, of saints and angels, in ivory and wood—some of which date back to the 16th century, and are part of the museum’s collection

For the show, Hoskote has juxtaposed Souza’s work with Christian Indian sacred art—images of Jesus and Mary, of saints and angels, in ivory and wood—some of which date back to the 16th century, and are part of the museum’s collection

Despite living away from Goa—first in Bombay and later in London (1949-67) and New York, where he migrated to in 1967—Souza, says Hoskote, remained psychologically entangled with Portuguese India for the first four decades of his life. This was also the time before Goa’s annexation by the Republic of India in December 1961, where the Portuguese Empire was controlled by the dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, whose regime was supported by conservative Catholic clerics.

“A key reason for me [to do this show] was to read against the grain of our understanding of post-colonial Indian art, which is largely based on British India and everyone who was active in it. This leaves out the completely different routes to the Modern, which came through Lusophone India and Francophone India,” he says.

That brings us back to the grotesque and dark painting that has inspired this exhibition, which in stark contrast is displayed against a bright yellow wall. The men around Pope Pius XII are shown as scarred and monstrous figures. Several of them, he tells us, are distorted to resemble Hitler. “Pope Pius XII’s papacy was tainted by his connections with the Nazis, and his tolerance towards the regime, even though it appears that he simultaneously helped many victims of Nazi tyranny escape. After he dies, his successor, John XXIII, inaugurates a completely different way of being in the world. The church really opens itself to the third world. This is a crucial moment in the history of the church,” says Hoskote.

Rather than show Souza as a general rebel, Hoskote says he “wanted to look at what this painting was really telling us, and how it becomes a way of thinking back over a history of the Global South”. Souza was in London at the time, and was already being seen as a blasphemous figure. “What plays out here, is an artist who is deeply suspicious of orthodoxy and hierarchy, and is yet struggling towards some kind of spirituality.”

From here, the exhibition ripples out to show his other works that are part of the collection, which again are symptomatic of this obsession with home and religion. There are landscapes that are reminiscent of the idyll of Saligao, and imagery, which constantly move between the demonic and sacred. His still-lifes, one of which is on display, show an assortment of edible food like a loaf of bread, wine and fish, all religious symbols again. “They are suggestions of Holy Communion, the Eucharist, and the Last Supper. Souza is always presented as an anti-Christian figure, but it’s strange that the still-life works are saturated in the belief system he appears to be satirising.”

In a unique attempt to understand Souza’s influences and the time that he was practising, Hoskote juxtaposes his work with Christian Indian sacred art—images of Jesus and Mary, of saints, martyrs and angels, in ivory and polychrome wood—from the museum’s collection, and the religious paintings of his contemporaries. Notable are the works of Akbar Padamsee and Krishen Khanna, which are on display on a wall adjacent to Souza’s works. “Both Krishen and Akbar were fascinated by the Christ figure.” He takes us through Krishen’s Christ at Emmaus (1975). “[In this work] Christ’s eyes aren’t visible, but His stigmata are. So, what is He? Is He resurrected, or is He a phantom? Krishen stood at the altar of this mystery. With Akbar, Christ was always this sense of compelling figure, who had a quiet heroism, a quiet anguish. Souza, on the other hand, brought to Christian iconography a sense of relentless opposition.”

The sacred art objects that have been strategically placed against these paintings reflect on the dichotomies, while also contextualising his work. “This collection, with some of its objects dating back to the 16th century, has its origins in Goa, Daman and Diu, and beyond. The attempt was to recreate the world of Souza as a child. In some of his memoiristic writing, he talks about his early memories, about the church, the priestly costumes, the images of the saints. That was clearly operative in his mind. All the images he later makes, refer to these early impressions and continue to inform his artistic language,” he says.

For Hoskote, they offer a magnified portrait of the artist’s work, one that’s otherwise invisible. “It’s a richer way of situating his paintings, and bringing viewers into Souza’s world. Bombay gave Souza a larger experience of the world, and a socialisation into the art scene. But that whole part of his life is relatively well known—it is the received account. This show looks at the backstory. It’s like a secret memoir of Souza.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!