Leaving the movies as a disillusioned cinematographer, Hemant Chaturvedi attempts to find answers among the veterans of his fraternity in a new documentary

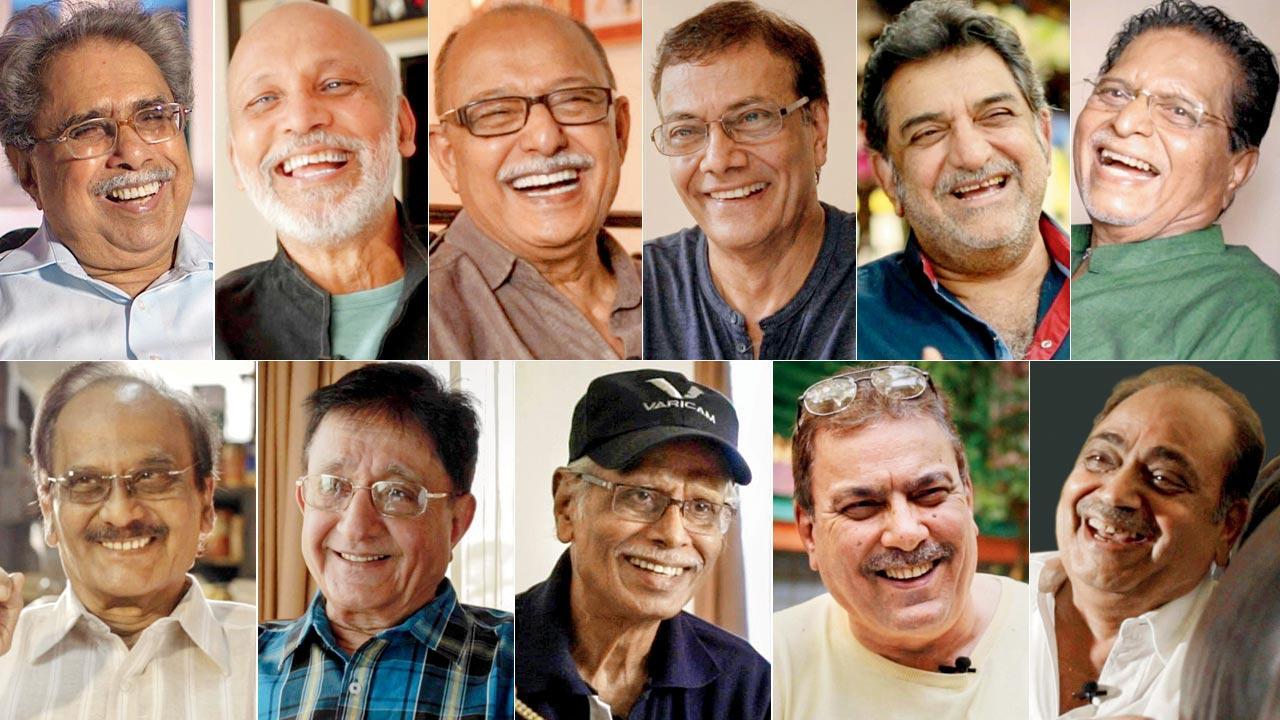

Peter Pereira, AK Bir, Barun Mukherjee, Jehangir Choudhury, Baba Azmi, Ishwar Bidri, Kamalakar Rao, Pravin Bhatt, Dilip Dutta, Nadeem Khan and Sunil Sharma, who all feature in the documentary. Pics Courtesy/Hemant Chaturvedi

Cinematographer Hemant Chaturvedi’s “peculiar relationship” with his profession began somewhere post 2000, when he made his transition from television to the movies. This was the time when Chaturvedi had, unbeknownst to himself, become a tour de force, spearheading projects, which would set the tone for new age storytelling in Bollywood. There was Ram Gopal Varma’s Company (2002), followed that same year by Vishal Bhardwaj’s children’s horror comedy Makdee and Maqbool (2004). Aparna Sen’s critically-acclaimed National Award-winning 15 Park Avenue (2005), which explored the relationship between a young woman suffering from schizophrenia and her divorced sister, came soon after.

Despite such an enviable oeuvre that only grew with time, Chaturvedi’s relationship with cinematography became more and more complicated. “That eventually culminated in me taking a decision to move on,” he shares. “I realised that the nature of the beast was such that it went against my fundamental [values], and that I was not going to change. I, for some reason, came to be known as the enfant terrible of cinematography.” Looking back, he thinks such a narrative suited many in an industry that was becoming cut-throat. “And so, for someone like me, who was not a competitive person, work became scarce,” he adds. “I remember having to wait for two or three years for my next offer. This was absurd. It’s a horrible feeling to wait for your next job—never knowing when it’s going to come to you. You end up not doing so many other good things, because you do not want to start that in case something else turns up.” After a lot deliberation, Chaturvedi decided to call it quits in 2015—the poor box-office run of the Akshay Kumar and Sidharth Malhotra-starrer Brothers, produced by Dharma Productions, cemented this decision.

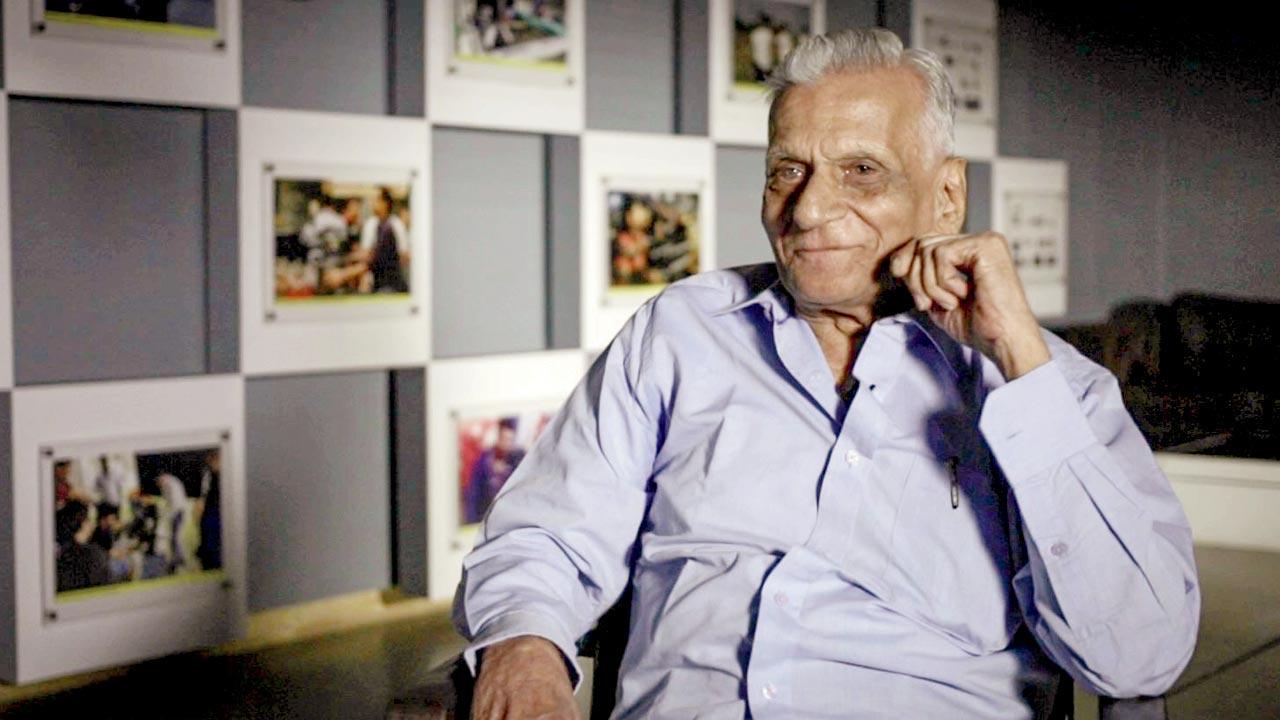

Octogenarian SM Anwar used to clean sockets and cables for a company in Pune, before he landed the job of camera operator on Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975). Pics Courtesy/Hemant Chaturvedi

Octogenarian SM Anwar used to clean sockets and cables for a company in Pune, before he landed the job of camera operator on Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975). Pics Courtesy/Hemant Chaturvedi

The disillusionment notwithstanding, Chaturvedi, who by then had begun experimenting with still photography, continued to have several unanswered questions about his profession, which he had dedicated nearly three decades of his life to. “I couldn’t understand how [when] someone worked with so much commitment, passion and honesty, what is that one thing that takes away the joy of being successful and engaging in better work.”

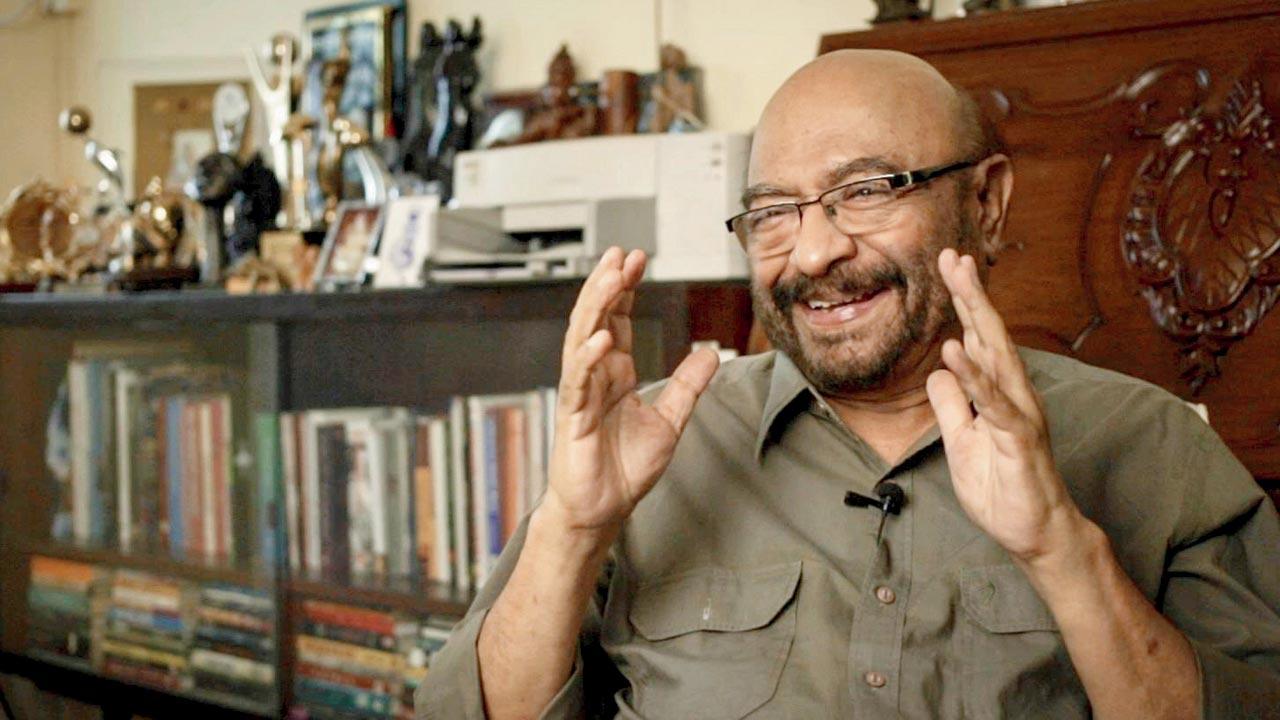

It’s around this time that he embarked on a documentary project, which would take him more than six years to realise. “In the late 1980s, when I was working as an apprentice, I had reached out to many senior cinematographers for work,” says Chaturvedi. Jehangir Choudhury, whom he had met in 1985, while assisting on a Merchant Ivory production, was the first real inspiration. “I was still studying at St Xavier’s College [Mumbai] then… Seeing him create all this magic from behind the lens, got me really excited,” he recalls. After returning from Jamia Millia Islamia with a mass communications degree, he tried meeting many of these cinematographers again. “But none of them had the space to hire me as an assistant. Govind Nihalani had accepted my request [in 1991], but just two weeks before the start of the film, I got a call saying that he was giving the opportunity to [playwright] Vijay Tendulkar’s son. I missed out on that, too.” But, this was also the era of the television boom, and Chaturvedi eased into it seamlessly. “I ended up being a 100 per cent self-taught cinematographer. I had no choice, but to teach myself.”

Director-cinematographer Govind Nihalani, whom Chaturvedi missed an opportunity to work with in 1991, is also part of the film

Director-cinematographer Govind Nihalani, whom Chaturvedi missed an opportunity to work with in 1991, is also part of the film

His only regret was that he couldn’t work with any of them. The opportunity to understand their body of work only came only after he made the switch in his career. “I thought why not reconnect with these people whom I had come to admire, speak to them about their journeys, compare it with my own, and see what emerges from these conversations, which would answer every query that I ever had. I was hoping that it would help me understand the purpose of my own life.”

Between December 2015 and January 2016, Chaturvedi met with 14 elderly veteran cinematographers, including SM Anwar, Dilip Dutta, Pravin Bhatt, Kamalakar Rao, Baba Azmi, RM Rao, Ishwar Bidri, AK Bir, Nadeem Khan, Sunil Sharma, Barun Mukherjee, Peter Pereira, as well as Nihalani and Choudhury, doing extensive video interviews on his DSLR, and gathering nearly 40 hours’ worth of footage.

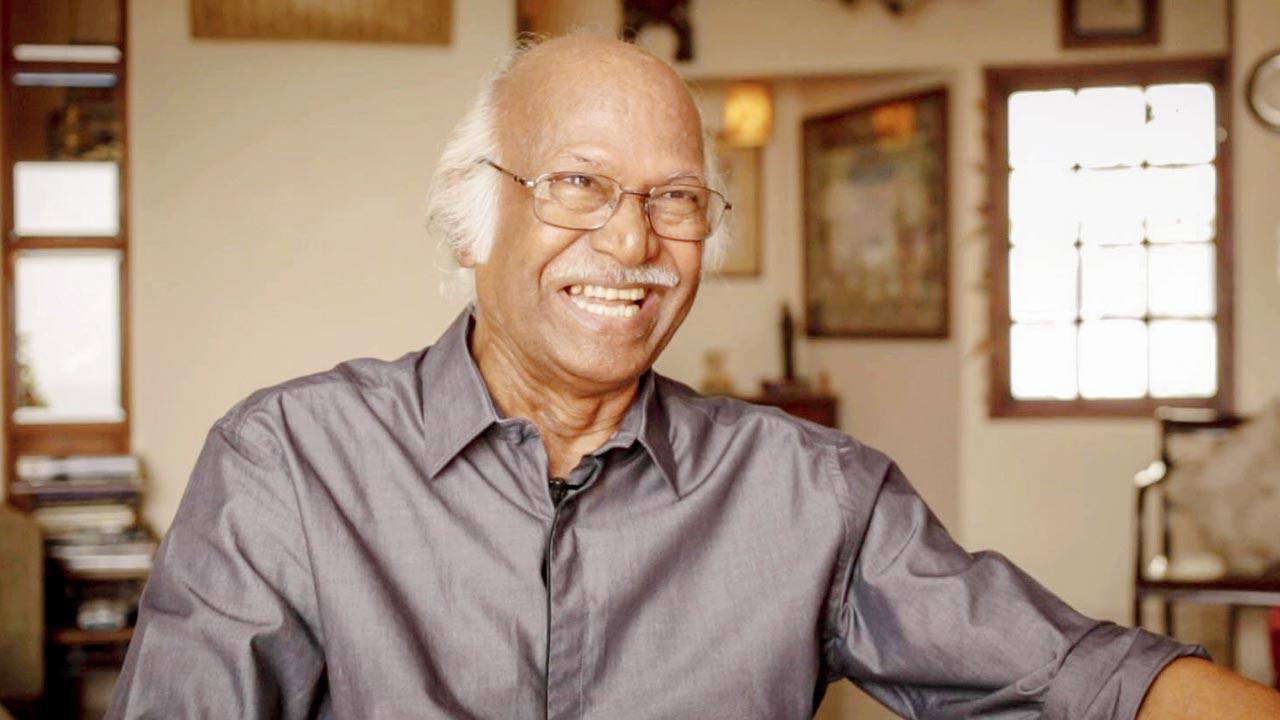

RM Rao has shot over 4,000 commercials during his career as cinematographer. “There was a period between the 1960s and ’70s, when if you went to the theatre, you’d only see commercials shot by Rao on screen”

RM Rao has shot over 4,000 commercials during his career as cinematographer. “There was a period between the 1960s and ’70s, when if you went to the theatre, you’d only see commercials shot by Rao on screen”

The videos, which sat in his hard-drive for the longest time, are now part of a soon-to-release documentary titled Chhayaankan: The Management of Shadows.

“All of them had a very interesting trajectory. Some of them had cautiously withdrawn and given up, some had moved on to do other things, some were still doing the odd shoots here and there, while a few were in a state of denial that their career was over. This acceptance or change in their fate had an effect on their personalities, of course,” he says.

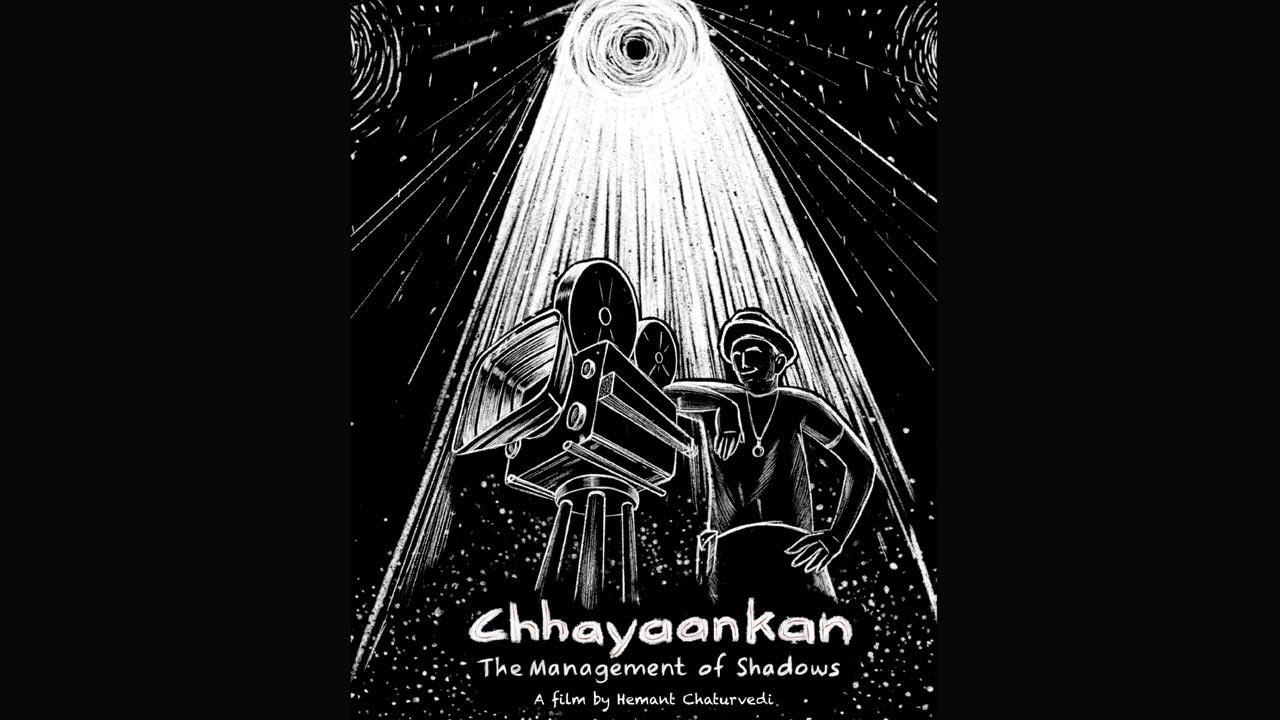

The poster of the documentary, Chhayaankan: The Management of Shadows

The poster of the documentary, Chhayaankan: The Management of Shadows

Chaturvedi doesn’t have a real excuse for delaying the documentary, except that he got busy with his other projects. “But in December 2020, when I heard that Ishwar Bidri passed away [at 88], and that Nadeem Khan was in coma for the longest time, I felt this huge sense of guilt. I realised that if this film wasn’t seen by the people [who were cast] in it, it would be a matter of tremendous shame,” adds Chaturvedi, who had spent a significant part of 2019 and 2020, including the lockdown, travelling the length and breadth of the country, documenting single-screen theatres.

Though he had a “gigantic inventory of unfinished work, this one took priority” and in June 2021, Chaturvedi began work on editing the film, shuttling between Mumbai and Pune, where his editor Suchitra Sathe, an alumnus and faculty member of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) was based.

Photographer Hemant Chaturvedi recorded the interviews between December 2015 and January 2016, editing the film only last year. Pic/Suresh Karkera

Photographer Hemant Chaturvedi recorded the interviews between December 2015 and January 2016, editing the film only last year. Pic/Suresh Karkera

While revisiting the original videos, he realised that the film, which has been pared down to 138 minutes, is not just about the journey of these cinematographers in the movies, but also their personal stories, pet peeves and relationship with the crew they worked with. “Now, I feel I know them more intimately, and I am losing them one after the other… just knowing that has been emotionally draining. I also often wonder had I ever got to work with any of these people, would my work have been different in any way?”

Between the 14 of them, they’ve shot nearly 750 films and 10,000 commercials. “That is the kind of span one had in that era. It’s just astounding to see how much work they did then. Pravin Bhatt alone has shot 120 feature films. He started in the black and white era, and ended with his son Vikram Bhatt’s film around eight years ago. Then there is RM Rao who has shot 4,000 commercials; there was a period between the 1960s and ’70s, when if you went to the theatre, you’d only see commercials shot by Rao on screen,” says Chaturvedi.

He says that the reason why many of them managed to hold on to their careers was because it was “an era of very long relationships”. “People would work together for much longer, and there was a certain loyalty and camaraderie then, which kind of eroded in the mid-1990s, when there were just too many people and too much work.”

One of the issues that he has dealt with in the film is the period when the film industry’s visual standards, he feels, had “dropped to zero”. “Most of the scenes would be shot in these bungalows with the curtains drawn. The only difference between a day and night scene, would be if the decorative lamps on the set were switched on or off… it was as bizarre as that,” he shares, explaining that this trend was observed after the studio system fell apart. “When that happened, actors started signing on multiple films, and because they didn’t have the time to come for shoots, a movie would take years to complete. A producer, who couldn’t keep a set standing for that long, would then move the shoot to a bungalow. That’s how these started becoming popular.” Some cinematographers submitted to the circumstances.

Among the more interesting journeys was that of Anwar, who is now in his 80s. “Anwar saab had a diploma in radio from an institute in Pune, and had been working for a Parsi company, where his job was to clean sockets and cables. Later, he was shunted to the camera department of the same company. His work got him to Bombay where he joined as a camera attendant at Eagle Films for a salary of R25 per month,” says Chaturvedi. Anwar was spotted accidentally by renowned cinematographer Dwarka Divecha, who asked him to do close-ups of a fight sequence they were shooting. On seeing the rushes, an impressed Divecha called on Anwar, only to learn that he had perfected his camera skills shooting birds on the terrace. Anwar went on to work as camera operator for Sholay, before helming Ramesh Sippy’s Shaan (1980).

Chaturvedi is planning to showcase his film in the festival circuit soon. He is also hoping to hold a private screening for cinematographers, especially those who have made it to the film. Each of the interviews is being edited as a standalone interview, which he intends to upload on YouTube. “I wanted to say how tortured I feel, sometimes, because I missed so many people who passed away in the last seven to 10 years prior to 2015, when I filmed these interviews… I wish someone before me had thought of this and documented so many people, who are gone forever. [Having said that] I want this to be a joyous celebration of people from an era where they were overachievers and under publicised, unlike our era of underachievers, over publicised.”

750

Number of films the 14 cinematographers featured in the documentary have shot between them

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!