They know there aren’t too many of them, but aren’t sure exactly how many. And each one must be saved. Indians living with the rare Bombay Blood Group must network, volunteer and educate if they are to watch out for kindred souls in a country where a national rare blood registry is still under-production and ID proofs don’t list blood types

Media professional Deepakkumar Eshwaran, 36, learnt at age 26 that he was not O positive but had the rarest of rare blood type Para-Bombay. A country of a billion has just 30 registered donors of this blood group. Pic/Satej Shinde

Mahesh Krishna Ghag has hit a century. The man who works as labour contractor at SEEPZ Andheri has donated blood one hundred times. Now 52, Ghag first became a donor when he was 19 and his grandmother needed blood after a surgery following a leg fracture. The day after, a call from the hospital informed him that he was one of a kind. The perplexed teen learnt that his blood group was one of the rarest around, and named after the city he lived in.

One in 10,000 Indians have the Bombay Blood Group (BBG) also called the HH blood type or the ABO blood group, making Ghag part of a tiny but close knit community. Members of this coterie cannot donate blood at will like the rest of us. This means that transfusion is a challenge. Ghag tells mid-day that he moves on a donation request only when he receives a call from KEM Hospital or one of the non-profits he is connected to. Ghag is part of a miniscule group of 450 registered donors in India, says Vinay Shetty, vice-president of Think Foundation, the Mumbai-based non-profit. The lack of a national survey means that we are unaware about the total number of Indians who live with this blood type. What we do know is that the frequency is highest in India, and Mumbai makes up for a chunk; the type is rare in the Caucasian population. The probability of finding a person with Bombay phenotype is one for every 2,50,000 people worldwide. India has the highest number with one Bombay blood type per 7,600 people. Consanguineous marriages or inter-familial unions between individuals related by blood are identified as one of the reasons for the prevalence of this blood type.

Deepakkumar Eshwaran is among the very few people with Para-Bombay blood group in the country. In the absence of a nationalised card mentioning his rare blood type, Eshwaran has to carry the blood group report from NIIH where ever he goes. Pic/Satej Shinde

Borrowing its name from the city where it was first discovered, BBG became known to the world in 1952. Dr Swati Kulkarni, deputy director (Scientist E) and Head of Transfusion Medicine at ICMR-National Institute of Immunohaematology (NIIH) tells mid-day that the international recognition of the discovery by Dr YM Bhende and Dr HM Bhatia at KEM Hospital led to the acknowledgement of the need for developing blood group research in India. With this vision, the Blood Group Reference Centre (BGRC) was started in 1957 under the aegis of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) to develop specific activities related to blood groups and blood transfusion. Dr Bhatia was its founder director. In 1952, the researchers published a study in British medical journal, The Lancet, stating that “a ‘new’ blood group character related to the ABO system” had been found. This was an important event in the field of immune-haematology.

Shetty says that the discovery followed after the arrival of a blood transfusion patient at KEM. When his sample was sent to the blood bank for cross-matching and grouping as per standard procedure, the technicians found that the red blood cells (RBC) grouped like the O group. The patient was administered O blood type, but when he developed a haemolytic transfusion reaction caused by the destruction of RBCs by the immune system, the process was stopped.

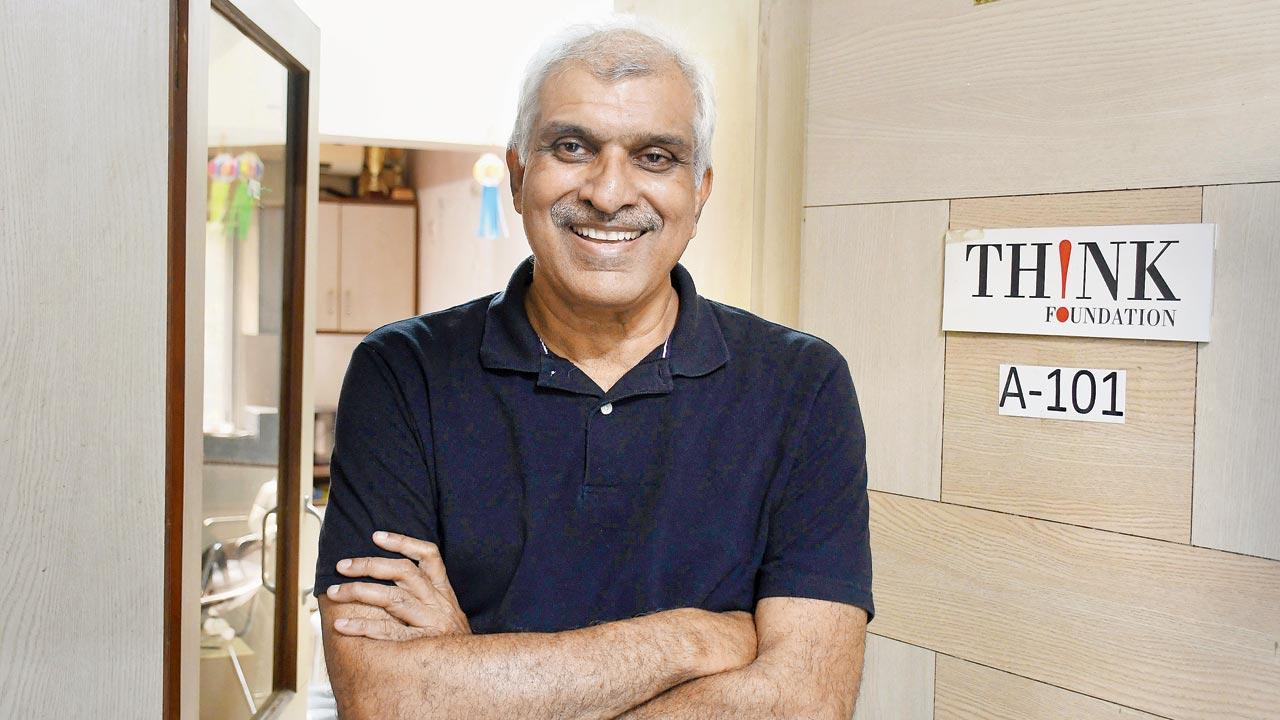

Vinay Shetty of Think Foundation says people with Bombay Blood Group are universal donors, but can only receive blood from within the Bombay Blood Group community. Pic/Ashish Raje

Vinay Shetty of Think Foundation says people with Bombay Blood Group are universal donors, but can only receive blood from within the Bombay Blood Group community. Pic/Ashish Raje

The study by Bhatia, Bhende and Dr CK Deshpande revealed the presence of a blood group that was neither A, B, AB or O.

It was christened the Bombay Blood Group.

“The precursor protein from which all blood groups are formed is termed the ‘H’ antigen,” explains Shetty, adding, “the ‘H’ antigen either translates into the ‘A’ antigen [the blood group is then called ‘A’] or ‘B’ [the blood group is then called ‘B’] or both ‘A’ and ‘B’ antigens [the blood group is then called ‘AB’] or it remains ‘H’ [the blood group is called ‘O’]. Earlier the detection of ‘O’ was based of the absence of both ‘A’ and ‘B’ antigens. In the case of BBG, there is an absence of the ‘H’ antigen itself, and the group is therefore termed ‘OH’.”

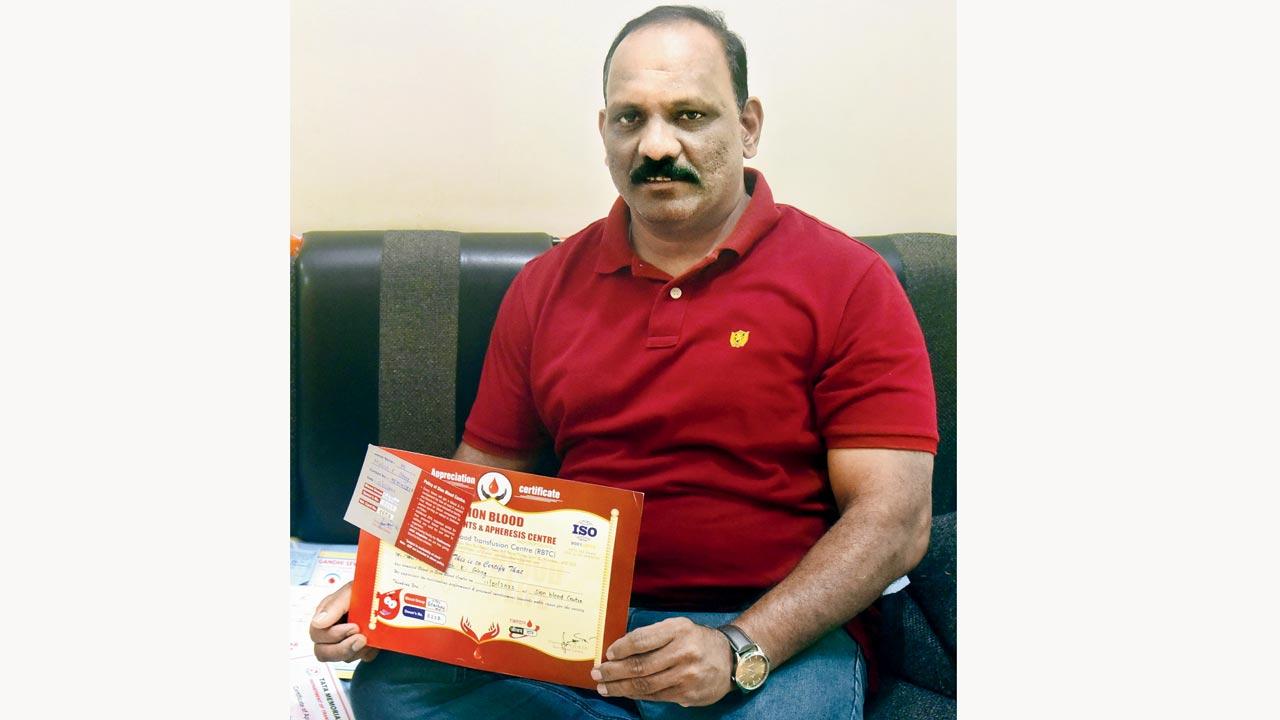

Mahesh Krishna Ghag has donated his rare Bombay Blood Group at least 100 times, after he got to know of it in 1990. Pic/Shadab Khan

Mahesh Krishna Ghag has donated his rare Bombay Blood Group at least 100 times, after he got to know of it in 1990. Pic/Shadab Khan

Last week, two Mumbaikars having BBG flew to Vietnam to donate blood to a newborn.

Ashish Nalawade, chief engineer in the Malad-based firm Tecnimont Pvt Ltd, was one of them. He was accompanied by Thane resident and teacher Pravin Shinde.

“We made an air dash on February 15, just a few hours after receiving the call for donation. Our blood was taken, but it did not match with the infant. Fortunately, they found a donor in Vietnam itself,” Nalawade, whose elder sister also has BBG says.

Rajat Kumar Agarwal, Ashish Nalawade and Dr Swati Kulkarni

Rajat Kumar Agarwal, Ashish Nalawade and Dr Swati Kulkarni

Lack of awareness about the existence of the blood type means that when Nalawade reveals his group, he is mocked. “People tell me, ‘Haan... mera blood group

Nashik hai’.”

In a bid to close the gap, all blood banks are now liable to inform the individual when they come across BBG and connect with non-profits Think Foundation and Bengaluru-based Sankalp India Foundation.

Volunteers then get in touch with the individual and their families and offer information and counselling.

Unfortunately, not all laboratories have the facility to detect BBG and people continue to believe that they have the O blood group.

“On initial testing, BBG appears as O. Only after testing the RBCs with the anti-H reagent and undertaking serum antibody testing, can we further establish that the person is of the Bombay Blood Group,” Dr Kulkarni explains. “Once detected, additional serological tests need to be done to confirm the blood type. Only trained and experienced blood bank personnel can do this.” Because not all blood banks routinely carry out anti-H testing, they tend to miss detecting a BBG individual. “In such cases, well defined algorithms about when to suspect and implement test methods for confirming the blood group need to be recognised in blood banks,” she suggests.

This confusion between O and BBG often leads to panic, says Shetty. “When O blood that is provided by a donor to a BBG patient does not match with the sample, subsequent tests done at the eleventh hour often reveal the presence of the Bombay Blood Group [leaving the patient’s family anxious].”

The rarity doesn’t end here. BBG has a sub-group called Para-Bombay, which according to Shetty, has only about 30 registered donors in India. That’s 30 in a country of 1 billion. Of these, only a handful are eligible for donation owing to age and health conditions. Individuals with this blood type can receive blood from BBG donors, but they cannot be donors for BBG persons.

Kandivli resident and media professional Deepakkumar Eshwaran, 36, learnt that he had the Para-Bombay blood group in 2013, a whole 26 years after his birth. “I learnt I was a BBG person in 2011 after donating blood at a college camp. I thought it was a prank until doctors counselled me. Two years later, after my saliva was tested, did I learn that I had the Para-Bombay blood group,” he says. Until then, he believed that he was O positive.

In the absence of a nationalised card system that can help identify individuals according to their blood type, Eshwaran carries a copy of his blood group report specially issued to him by NIIH.

“It is nothing to be worried about,” he assures.

Rajat Kumar Agarwal, office bearer at Sankalp India Foundation, a non-profit that works in the field of blood donation and thalassemia and has 120 active BBG donors registered with it, says that even the driving license (DL) in India fails to mention rare blood types.

“There is no drop-down option on the registration site to denote an individual as BBG on the licence. Since a BBG person cannot be transfused with any other blood type, having this information printed on the card or any other nationalised document is an absolute necessity. It would be of critical importance if the person faces an emergency like a road accident.” Agarwal says that his letters to authorities have been ignored.

Dr Manisha Madkaikar, Director, ICMR-NIIH agrees that the mention of rare blood groups in government issued ID proofs like the passport, driving licence, Aadhar card, should be mandatory to help arrange blood transfusions in an appropriate and timely manner during emergencies.

With about four to five units of BBG in stock across the country at any given point in time, non-profits claim that while a robust network makes BBG donors available in all parts of the country and even neighbouring areas like Sri Lanka and Pakistan, more needs to be done. In fact, even within the country, they identify Maharashtra and South India as better equipped than the north and east. Maharashtra is believed to throw up cases of BBG, as do areas like the union territory of Puducherry. But in the absence of a national survey to test people with BBG in the country, donors are next to nil in the north of the country, says Agarwal.

“Several studies have been carried out [in Maharashtra] and it was found that BBG occurs in 0.02 per cent of Ratnagiri natives. Individuals of this blood group have also been found in Puducherry [0.008 per cent], Tamil Nadu [0.004 per cent], Karnataka [0.005 per cent], Andhra Pradesh [0.05 per cent] and also in some tribal groups of the country. It is less common in the northern, central and eastern parts of India,” Dr Kulkarni shares.

Dr RS Balgir, scientist and former deputy director and HOD, Biochemistry, Regional Medical Research for Tribals (ICMR) conducted a study among members of the Bhuyan tribe of Orissa and found an incidence of BBG as one in 278. He also studied the Kutia Kondh tribe in Kandhamal district of Orissa and found 1 in 33 incidence of the Bombay phenotype. Balgir had linked the high prevalence of BBG in these tribes was to the practice of endogamy and consanguinity.

The good news is that at the national level, efforts to set up a National Rare Blood Group Registry by ICMR are underway. “Like BBG,” says Dr Kulkari, “there are many other rare blood groups including Pnull, S-s-U- Rhnull [often called golden blood]. Finding blood for individuals of these blood types is extremely challenging especially in an emergency. We have been screening donors from different regions of India to identify rare blood types. A list of rare donors is being maintained. In future, we hope to establish a national registry of rare blood donors for the systematic requisition and acquisition of rare blood type supply and improved transfusion therapy among blood recipients.”

Sankalp is also working to set up its own blood bank in Bengaluru with the added facility to freeze rare blood group units for up to 20 years through a process called Cryopreservation. “This is regular practice globally. In India, the defence ministry undertakes it,” says Agarwal. Setting up the facility, equipment procurement and staff recruitment is complete. We are hoping to acquire the license to start operations soon.”

For better utilisation of short in supply rare blood groups, Sankalp is nudging medical professionals to discuss alternative blood therapies instead of external blood transfusions. “We follow up with hospitals for every unit [of BBG] that is sent to them. If it is not utilised, we make sure that it is rerouted to someone else within the 42-day shelf life period. If stock is available somewhere in the country, it is flown as air cargo to the place of requirement to avoid a fresh donation,” he adds.

Agarwal recalls a recent case where a pregnant woman from Agra in Uttar Pradesh had to undergo a surgical abortion at full-term. “Doctors believing that blood may be required for her during surgery, sent out a BBG unit request. We sought all the documents to validate that she had the Bombay Blood Group and also sought her haemoglobin report.” On finding out that the woman had 13.5 g/dl haemoglobin count, Agarwal says that he informed her doctors that they would be available as backup. “The patient was nowhere close to anaemic and a donation if made in haste could end up in wastage. The surgery was successfully completed,” he says.

“In such cases, the medical fraternity should explore the option of using erythropoietin injections which push the body towards natural production of RBCs to make up for any blood requirement,” he adds. “Another option is autologous blood donation for patients with more than 12.5 g/dl haemoglobin. Here, blood is taken from the patient and transfused back if needed. The safest blood to take is your own, plus it reduces pressure on rare blood donation.”

1/10k

Number of people in India who are likely to have this rare blood type

350-400

No. of persons with the Bombay Blood Group identified in India to date

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!