In a time when hook-ups are markers for successful, desirable, universally liked persons, mid-day discusses sexual abstinence with women who are—surprisingly—enjoying the retreat

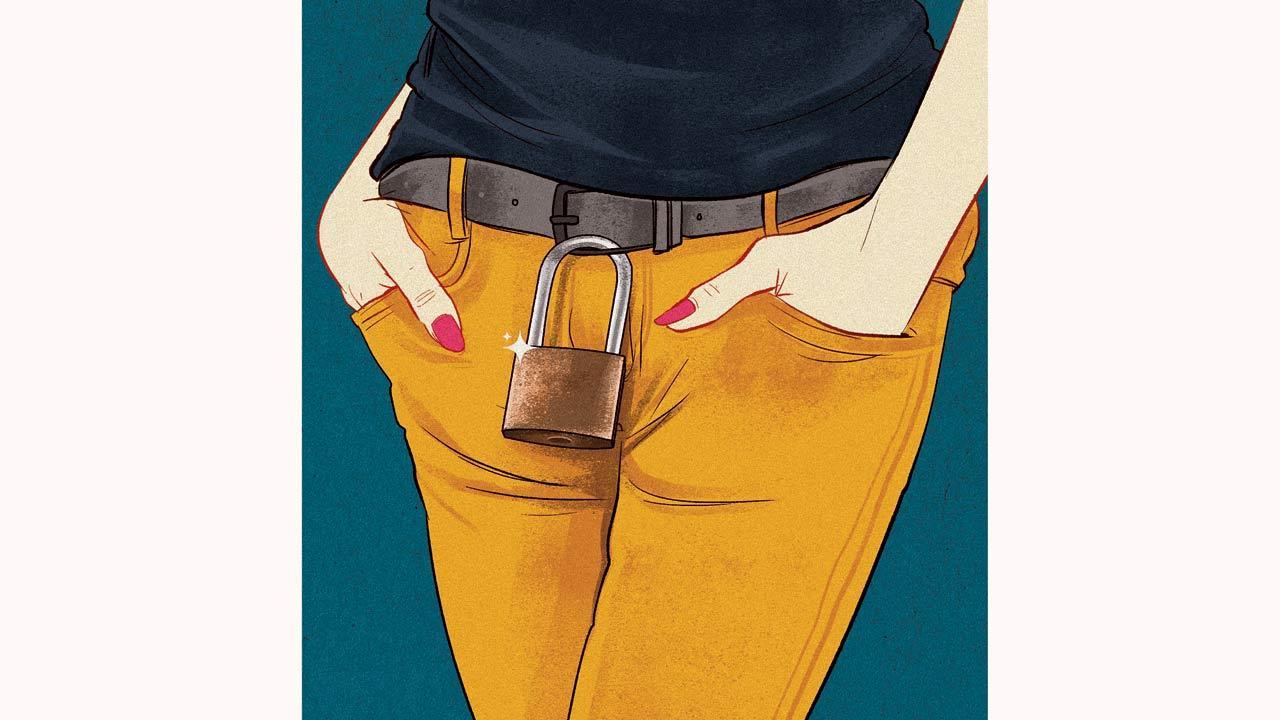

Illustration/Uday Mohite

In a time long, long ago, when cable television came in and beamed the American soap opera The Bold and The Beautiful into our living rooms, what left most hormonal teenagers aghast is how everyone was “always in the mood for romance”. Count the amount of times, per episode, two people exchange bodily fluids in Grey’s Anatomy, which has been running for 20 seasons.

It’s an overriding theme in the overculture: You are successful, desirable, universally liked and all-round happy if you are “getting some” all the time.

Virility, and the ability to be able to express it with consent is hyped up so that one can sell things to those feeling low for not hooking up thrice a day after mealtimes. Those with a natural ebb and flow of the libido. Insecurity is great for the economy.

You can sell them an expensive watch and a large car which will get them noticed, which will need an expensive dress and handbag, of course. And you’ll need a gym membership to look good in those. You’re taking Pilates, no? Have you bought the kit for it?

Neha Bhat; (right) Tanvi Mallya, neuropsychologist

Neha Bhat; (right) Tanvi Mallya, neuropsychologist

In these hypersexual times, many individuals are abstaining out of choice, not for moral or religious reasons, nor as a side-effect of an illness or asexuality. They’re just saying “No, thanks” or “not now”.

An IT professional in her early 40s who has been celibate for more than seven years, finds it hard to be physically intimate outside of a formal relationship. “I was initially an emotional wreck after my marriage ended,” she says. “At first, I didn’t want to be close with anyone. Later, a voice [maybe my upbringing] told me I was wrong [to be with someone else].”

Neha Bhat, who goes by the moniker Indian Sex Therapist on Instagram, says, “We are living in a shapeshifting culture between newer and older India. There’s a lot of strife and chaos, and mixed intergenerational values. So, confusion about who we are and who we want to be manifests in our sexual and psychological lives.” Celibacy, says the author of the book Unashamed: Notes from the Diary of a Sex Therapist, can be one of those very powerful points of sexual fluidity that people choose for themselves.

“In India,” adds Tanvi Mallya, a neuropsychologist who specialises in working with adults 50 years and above, “traditional values often coexist with modern perspectives, and sexual abstinence can reflect a blend of individual and societal considerations. Some might choose it after a significant life event. Psychological reasons such as the desire for emotional healing, self-reflection, or the need to establish a stronger sense of self before engaging in intimate relationships again, also come into play.”

Like many people we spoke to, an animal welfare worker in her late 30s, says the period of celibacy of about three years after her divorce helped her re-calibrate who she was and what she wanted. “I married my childhood sweetheart,” she says, “with whom I had been since I was 15. He was my first everything—boyfriend, kiss and sexual partner. It felt sanctioned. After my divorce at 32, I had to reacquaint myself with what I liked, what my physical needs are and what my rules for sexual engagement would be.”

This introspection and self-knowledge simmered underneath a dominant culture which told her to get on a hook-up app, be open to strangers while travelling, and have one-night-stands with men whose relationship status was unknown. “Everyone kept pushing me,” she says amused, “to go out and have ‘fun’, as a panacea. I tried it a bit, but I felt like I was numbing my emotions.”

It got a bit more confusing for her as dating rules had changed from the last time she was single—which was when she wasn’t even technically an adult. This new permissive, no strings attached and casual landscape was disorienting, and she wanted time to make a map for herself.

“Today, where casual relationships and quick connections are often facilitated by technology,” explains Mallya, who is visiting faculty at St Xavier’s college, ‘some people may choose celibacy to counterbalance the fast-paced, often superficial nature of modern dating. The prevalence of situationships might raise questions about the depth and meaning of these interactions, prompting a desire to step back and re-evaluate the approach to relationships. For others, the overwhelming availability of sexual opportunities might lead to a sense of burnout or disillusionment, making celibacy a necessary retreat.”

Author Vasudha Rai recently spoke on Instagram about her periods of celibacy. “I’m in my 40s,” she told this newspaper, “and have had periods of celibacy in my 30s and 40s that lasted months or even years. I must add that I am very sensual and hedonistic: I love visiting spas, going for massages, taking care of my skin, wearing red lipstick, keeping my nails long and wearing sexy clothes. I just haven’t been into sex.”

That this pressure to be a single-minded sexual creature is special, seems more apparent to women. It was mostly cis het women who volunteered to talk to us. All sexes would certainly have this experience, but can’t help but wonder if cis het, homosexual and trans men feel the pressure to be constantly virile even more. Are you even a man if you are not thinking of sex every few minutes?

One of Rai’s periods of abstinence came after she had sex “under societal pressure”. When alone, she was surprised to find that she didn’t miss sex. “[One phase] revealed to me that I like celibacy, which is contrary to what the world tells you—that you need sex like you need food and water.”

In most communities, culture and religion dictate and sanction our sexual life, its frequency and intensity. “We have a very linear sexual narrative,” says Bhat, “that you are asexual, sexless or sexually repressed for a long time during puberty, then after 18-19 get married have lots of sex to reproduce one after the other, and by 40 45, go back to being asexual. This is not true to lived experiences.”

The IT professional found that, “I cannot get physically intimate without being emotionally involved. I also realised that I am stuck in my past relationship, and this state will continue infinitely. So, I decided that sex was overrated and gave up.” She candidly wonders if this is a case of sour grapes.

Rai finds “immense peace” in her celibate phases. “I miss intimacy and affection more than sex, and that sex without the two is animalistic, athletic, like a sport... and not very enjoyable.”

The animal welfare worker was left dissatisfied when sex did not automatically lead to emotional intimacy, which she assumed would follow. “I was used to the going hand-in-hand because my first experience of sexual intimacy sealed the fate that I would build a life with that man,” she says, “But in the modern dating scene, I [felt that I] was auditioning for sexual compatibility.”

One of the aspects that left her discontent was the impetus to discover other mutually enjoyable activities that may not be romantic.

“There is a strong societal emphasis on sexual relationships as markers of adulthood and fulfilment,” says Mallya, “The decision to be celibate can reflect a natural rhythm, an introspective phase where an individual seeks to understand themselves outside the context of romantic relationships.

This aspect of human experience is not always widely discussed, perhaps because it runs counter to dominant cultural narratives that equate sexual activity with happiness or success.” Think how often a nice suit or perfume is sold to a man with the promise that it will magnetise women to him.

The celibacy proponents say they are spending this time on what Mallya calls “meaning making” as per the theories of Austrian neurologist and psychologist Viktor Frankl from places of deep introspection and inner transformation. “Older adults may use this time to reflect on their lives, find deeper purpose, and achieve a sense of integrity,” she says. Other demographics also “experience significant inner transformation, as the brain forms new neural connections focused on emotional regulation.

Cognitive-behavioural changes lead to greater mindfulness and a re-evaluation of personal values.”

Most of the women who volunteered to speak to us agreed that they found they needed an emotional bedrock for sexual activity. The animal welfare worker’s solution was to marry deep friendship with sexual activity. “I made a friend who shared my values of sex being a private, consensual pleasure, not a notch on the bedpost to be announced,” she says. “We feel safe with each other to share a bed, without actively pursuing a romantic relationship outside it.” Their only rule is to let the other go if they fall into other relationships—sexual or romantic.

Mallya offers the perspective that from a psychoanalytic perspective, celibacy allows for the sublimation of sexual energy into creative or spiritual pursuits. “This can help resolve internal conflicts and integrate unconscious material into conscious awareness. It also promotes a more coherent and resilient sense of self—a peaceful, integrated, and purpose-driven inner life.”

There are downsides too, according to Mallya, such as a diminished sense of closeness or disconnection from others in a society that values romantic and sexual relationships. It could also be a way to avoid underlying fears, feelings of inadequacy, or anxiety.

“I am not actively dating, and go months without sex,” says the animal rescuer, “I want to design my life—where I want to live, how I want to live, whom to allow in and to what degree, my recreational activities and even daily rhythms. I want to know who I am, and I feel stronger recognising that I can be alone. It’s nurturing my soul and self.”

A party for one.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!