Do we live in a world where Nadaaniyan is greater than Superboys of Malegaon? Screenwriters, creators and studio executives tell us why good content is gasping for air while mediocrity is having a moment

Nadaaniyan

Last week, I went with a few screenwriter friends to watch Superboys of Malegaon. Reema Kagti’s film has that rare magical quality—of reminding people why they do what they do, which is so important for artistes to remember.

Last week, I went with a few screenwriter friends to watch Superboys of Malegaon. Reema Kagti’s film has that rare magical quality—of reminding people why they do what they do, which is so important for artistes to remember.

But, as we entered an empty theatre, I could see the heart-broken faces of my friends aged 25, 31 and 35. On most days, it’s safe to assume that a good movie can fix everything, but not that day. A large part of the post-movie conversation became about how good films are slowly being disincentivised by the system, while the same system backs mediocrity. The conversation then focused on the Internet’s hate-watch of the week—Nadaaniyan, starring Khushi Kapoor and Ibrahim Ali Khan, backed by Karan Johar.

Superboys of Malegaon

Superboys of Malegaon

I picked up the phone to speak to the commissioning lead at a notable streaming platform. “Many of these film studios just don’t want to put their a** on the line. If a show doesn’t come from a relatively successful creator, filmmaker, the studio doesn’t find it safe to bet on it. Star kids appear to be a safe bet because you can explain it through numbers on an excel sheet. I am sure someone on the team of Nadaaniyan had said, ‘we can get Saif to do some promotions’. It is all about recovering a cost. It’s not personal. It’s not even good business. It’s a lack of belief in themselves about what stories work,” they tell us.

For years, streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime were heralded as the great equalisers. They did offer us an array of fresh talent breaking away from Bollywood’s star-driven machinery.

When did that change?

A recent social media post by writer Cchintan Shaah said that these platforms are anything but the inclusive spaces they claim to be. Shaah, like many aspiring screenwriters, has spent years pitching scripts to OTT giants, only to receive templated rejections. “There are three standard responses—this doesn’t fit into our slate, our slate is full, we are already doing something on the same lines.”

Tabbar were critically acclaimed

Tabbar were critically acclaimed

“It often feels like they don’t even read my work,” he lamented in the viral post. His frustration has struck a chord among independent filmmakers and writers, who argue that these platforms have merely transferred power from Bollywood studios to the new elite of digital gatekeepers.

Are pitches even being read? One studio exec tells us, “Pitches get read. It is simply that unsolicited pitches are like the slush pile. The cold hard truth is that young talent seems to get promoted/noticed/picked up only if we know them. Everyone in corporate boardrooms loves to say ‘we have to be promoters of young ideas’ but it’s a punchline. That said, I also feel that many young writers who send in their cold pitches don’t have a sense of what the market is looking for. Right now, everyone’s on the hunt for a good horror or a Young Adult show. Or business legacy stories. But so many pitches are the standard cop and crime dramas. I don’t know how to bridge that gap. Maybe there could be some sessions, where studio heads and writers could communicate to each other.”

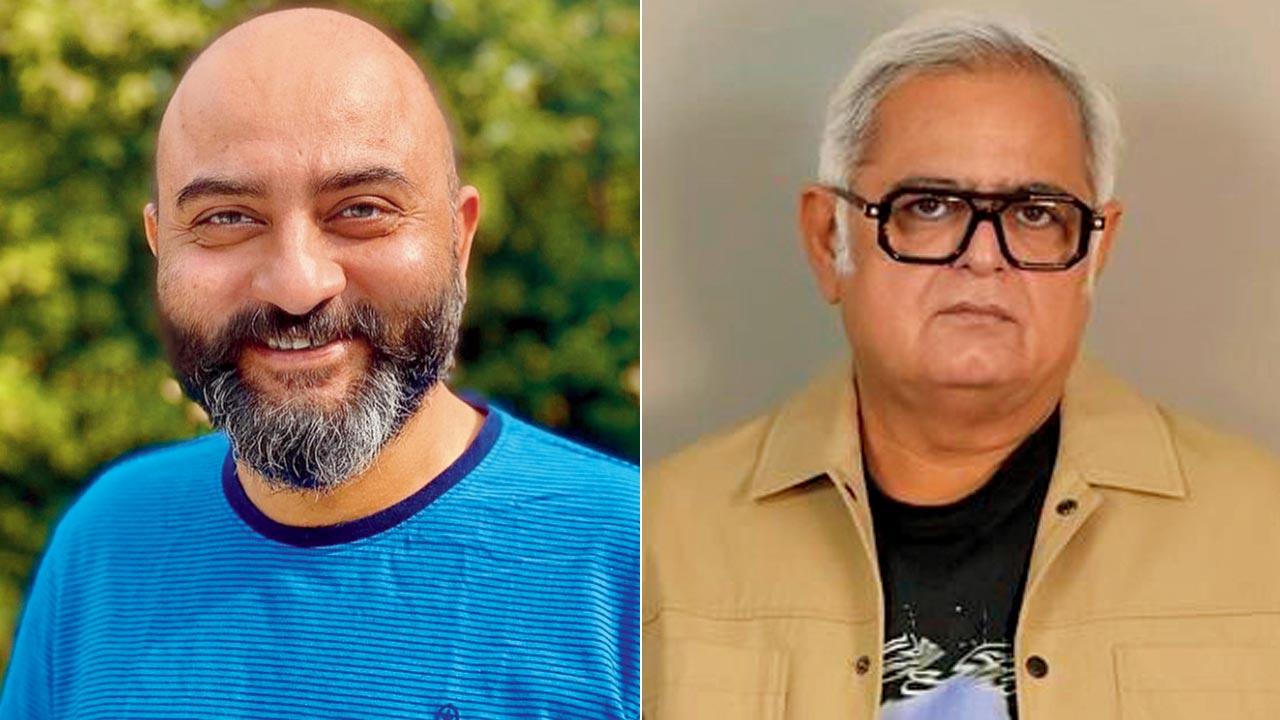

Ajitpal Singh and Hansal Mehta

Ajitpal Singh and Hansal Mehta

When the streaming boom kicked off in India, there was optimism that fresh, diverse voices would finally have a platform. The rise of content like Paatal Lok, Delhi Crime, and Scam 1992, all featuring relatively untested creators, seemed to validate this belief. However, many now argue that the doors are closing again, with green-lighting decisions being dictated by existing industry relationships.

A well-known screenwriter, who delivered a streaming hit this year, says, “Streaming isn’t television. It was supposed to be about making disruptive content. But the streaming heads in India come from a television background. I am not surprised at the decisions they are making. Cringe or not, Nadaaniyan did what it had to do—made enough noise for people in small towns to watch the film. It got them numbers. Something a great, nuanced show won’t be able to achieve. Sony Liv has a wonderful show called Tabbar. Ask around and you’ll know many people have not watched it.” I recall a conversation with Tabbar director Ajitpal Singh. He had told us, “I was an indie maker with a script. We went to small, medium, and large platforms. Some of them didn’t even read our pitch. There were excruciating periods of lull.”

Studio execs point out that every major slate announcement is a mix of star-led ventures and shows which are creative gems. Chaitanya Tamhane, who made Court, in a recent interview, said it’s a simple solution—you can always do one for the kitchen, one for the soul. Hansal Mehta, creator of Scam and Scoop, says, “It will need solid financial discipline, intelligent exhibition strategy, and marketing that is well-thought-out. Everyone has the data. But they need to have some faith in good talent. We need a shift in priorities.”

But maybe the audience needs to course correct too. “If you show up to watch a film with talented people, you are saying give me more of this. But if you watch bad movies, maybe you are a part of the reason,” a filmmaker who is making an actioner for a leading streamer told us.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!