Mumbai’s Zoroastrian-dominated Dadar Parsi Colony played host to an artist and believer who is keeping alive an extinct script through the flourish of her pen

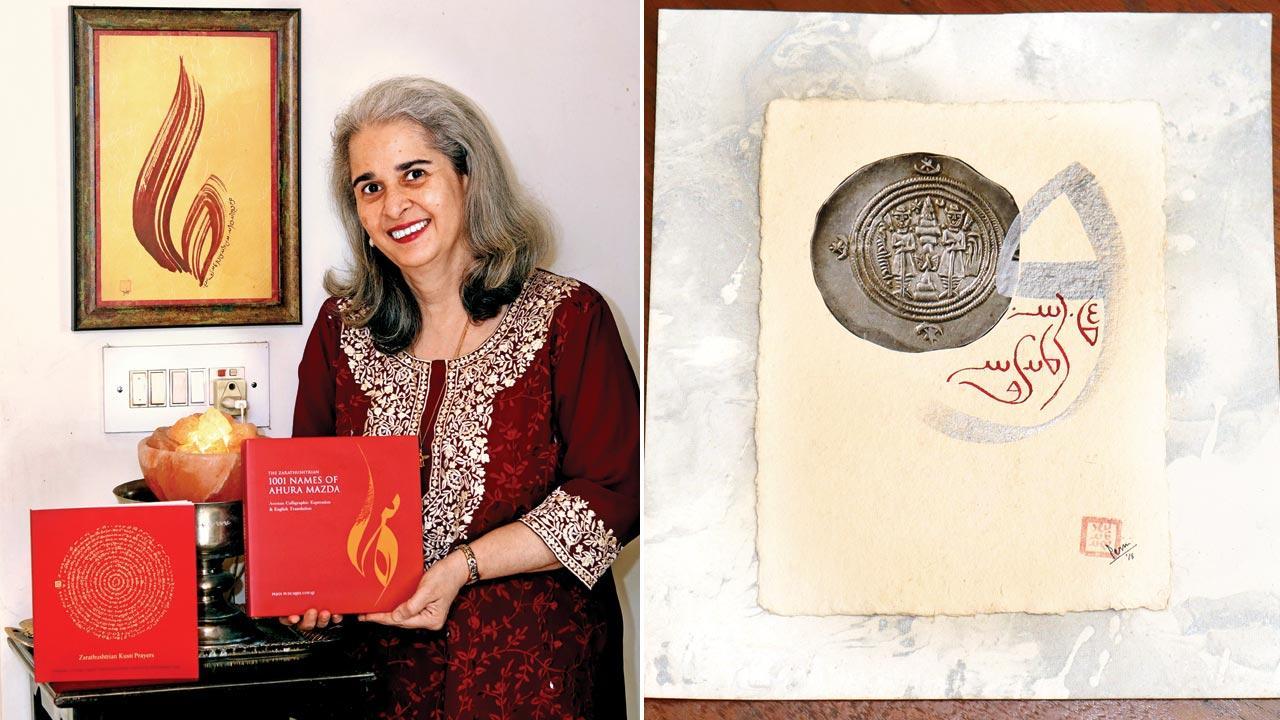

Calligrapher Perin Pudumjee Coyaji says she has been divinely guided to revive the ancient Avestan script; (right) This inscription of a coin features the prayer Kem na Mazda, which she calligraphed in Avestan

Perin Pudumjee Coyaji was just 25 when she decided to switch gears from industrial copywriting to calligraphy. It was 1996; a chance to study the art under master calligrapher Achyut Palav, whom she calls her guru, set her off on the path of rendering letters in artistic forms. “I was keen to do something more meaningful with my life,” she recalls. For nearly three years after, she travelled weekly from Pune to Palav’s Dadar office, to study the basics and return home in the evening, while also freelancing as a copywriter.

As a child, Pudumjee Coyaji was fascinated by old letterforms; one of her treasures was a lettering practice book gifted to her mother, Dinky Pudumjee, by a cousin. She was all of 11 when she began tracing Old English letters. Two decades later, she is known for her seminal work in reviving Avestan, an ancient East Iranian language that uses the Pahlavi script—a code script of 12 primary letters—in which the Avesta, or religious text of Zoroastrianism, is written.

Within the Parsi community, many have not seen the script; prayer books are typically printed in the English Roman script or Gujarati. A new Avestan script was introduced in sixth century AD, after which it survived not as a spoken language but a liturgical or sacred one. Avestan is used as an umbrella term to encompass both Old Avestan (spoken in the second to first millennium BC) and Younger Avestan (spoken in the first millennium BC). Old Avestan, say scholars, was similar in lexicon and grammar to Vedic Sanskrit.

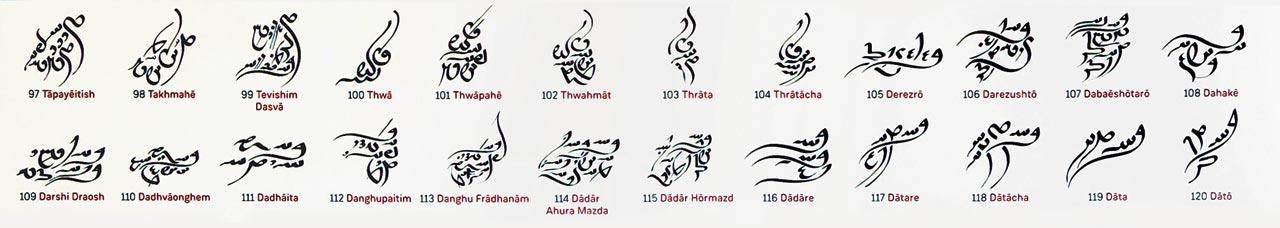

A vignette from a banner created for the World Zoroastrian Chamber of Commerce Global Conclave held in January. It showcases the 1001 names of Ahura Mazda, Zoroastrianism’s creator God, written in Avestan by her. For example, No. 98 is Strong, and 99 is Giver of Strength. Pics/M Fahim

A vignette from a banner created for the World Zoroastrian Chamber of Commerce Global Conclave held in January. It showcases the 1001 names of Ahura Mazda, Zoroastrianism’s creator God, written in Avestan by her. For example, No. 98 is Strong, and 99 is Giver of Strength. Pics/M Fahim

Palav’s thesis on the Modi script, which was used with the Devanagari script to write Marathi until as recently as the 20th century, inspired his student to find a project of her own. The challenge lay in sourcing research material from archives and genuine books written in Avestan. “When I finally decided to unearth the script, people in the know said that books in the language are available only in the Parsi madressas or seminaries. Dr Jeroo Coyaji sent me to the Vaidik Samshodhan Mandal (a library and institute of Vedic studies) in Pune, but they had a record of only alphabets, no prayers,” she says.

Coincidentally, a neighbour, Perin K Shroff, gifted Pudumjee Coyaji a 100-year-old book on Avestan grammar by Er Kavasji Edulji Kanga. “In it, I saw the Ashem Vohu, Yatha Ahu Vairyo and Yenghe Hataam prayers for the first time in the old script!”

Another milestone was receiving Avestan script prayers, an old 1931 edition of Bombay Parsi Association’s Khordeh Avesta, from Er Dr Rooyintan P Peer. Using these as reference material, she traced letters, blowing them up with a photocopier, and align them on a grid to get the proportions right.

From a spiritual perspective, she says, her journey has been divinely guided. During a trip to Iran in May 1998, she saw a priest reading out from an Avestan book. Seeing how Iranian children knew how to read the script, she longed for Parsi children in India to do the same. “I am not a grammarian, scholar, or historian,” she emphasises. “I just revel in copying out the script and sending it into the world.”

Her most recent work, The 1001 Names of Ahura Mazda, was released last year. In this, she referred to 1951 Gujarati booklet by Zoroastrian priest Ervad Kaikobad Edulji Karkaria.

Over the years, her efforts have involved creating framed prints, artworks, bookmarks, and prayer charms. Elders request the names of their grandchildren in Avestan. In the past year, she held community table sales in Pune. It was Mumbai’s turn yesterday at Dadar’s Palamkote Hall.

“When the sacred script enters your home, treat it as you do an honoured guest, with due respect and care,” she signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!