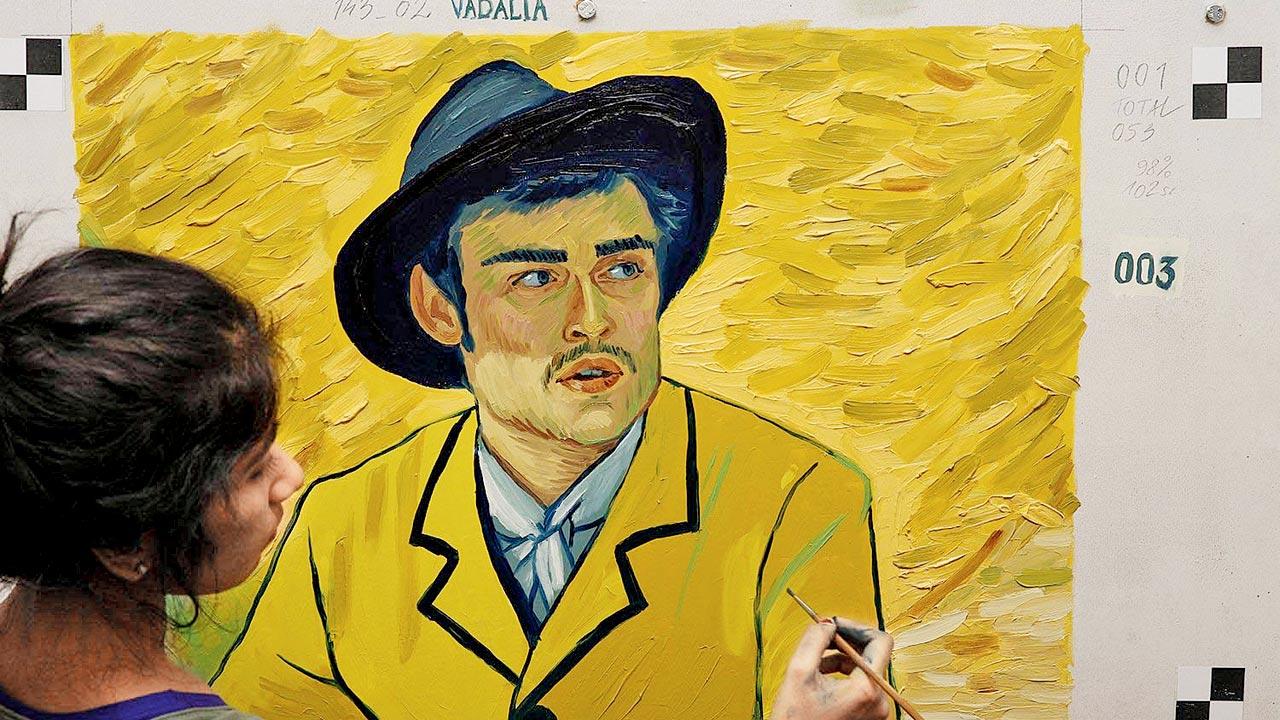

A Mulund-based artist, who was part of the team behind the world’s first fully hand-painted feature film and is readying to participate in the second, draws inspiration from Gandhara sculptures

Painter-animator Hemali Vadalia is awaiting her return to Poland to start work on The Peasants; (right) Vadalia’s self-portrait, which is a work-in-progress titled, Holding on or letting go. Pics/Satej Shinde

At the art studio in her Mulund home, painter-animator Hemali Vadalia is everywhere. Life-size oil portraits—some completed, others still works-in-progress—cover the sky blue walls of the room. In one self-portrait titled Yaad, Vadalia is fast asleep, her legs curled up in foetal position. In another, she rekindles a forgotten memory from school, when she was part of a prayer group. Except that this choir is only made up of doppelgangers, each bearing a different personality, but all Vadalia nonetheless. There’s also an unfinished painting on an easel, where her half-smiling reflection stares right through. “It’s easy to paint myself... I don’t have to hire a model. All I need to do is look into the mirror. The focus is not the subject, it’s the story,” Vadalia, 38, says.

In the room is a DIY mannequin of her upper body she made using a technique similar to the one adopted in papier-mâché. Only here, Vadalia enlisted the help of a relative to use black tape over a tee that she was wearing to mould it to her shape, later stuffing it with fibre. It helps her capture the scale of her subject in her work.

Some of these paintings were exhibited at a solo art show at the Nehru Centre Art Gallery in Worli this June. And yet, not much has been said about her. Which explains why Vadalia, despite being a co-creator of the 2017 Oscar nominee, Loving Vincent, the world’s first fully hand-painted feature film, continues to be a silent creator. “I was told to be patient,” she says casually, when we ask about her artworks finding a home.

With 350 paintings, Vadalia has contributed to about 30 seconds of the Oscar-nominated hand-painted film, Loving Vincent (2017)

With 350 paintings, Vadalia has contributed to about 30 seconds of the Oscar-nominated hand-painted film, Loving Vincent (2017)

Currently awaiting her return to Poland to start work on another ambitious project, The Peasants, Vadalia barely manages to contain her excitement. “It’s going to be a new challenge,” she says of the hand-painted film from the same makers.

Her earliest memory of dabbling in the arts was when she made rangoli with her mother. Learning to paint and make craft, she chose early on to let her interests remain hobbies, as she went on to pursue computer engineering at KJ Somaiya College. “A brief stint as programmer made me realise that I wasn’t cut out for it,” she says. Much to her parents’ surprise, Vadalia went on to sign up for a Masters degree in Animation Design at IIT Bombay, and started to look seriously at claymation stop-motion films and paper cutout animation. Around this time, in 2012, she happened to see a rough online trailer of Loving Vincent, a film that traces the life of the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, and, the circumstances of his death. “Though, I had no portfolio to speak of, I reached out to Dorota Kobiela [artist and director of the film], asking if I could work on the project. It was on a whim.” Barely disappointed about not hearing back from Kobiela, Vadalia decided to take up short courses on classical art first, at the Angel Academy of Art in Florence, Italy, and the Grand Central Atelier in New York. “Out of nowhere, in 2016, a friend told me about an opportunity that had opened up for Loving Vincent. This time, I was called in for an interview and a painting-animation test,” she shares.

For the next seven months, she worked out of a studio in the Polish port city of Gdańsk, with 125 artists from across the world. “We all were given a designated area in the studio, which had a light-controlled box, with a monitor, projector, and drawing board with a camera mounted on it, to make the paintings,” she says. The artists were given a previously-shot video of the film made with the original cast, and “character design paintings” as reference, which best reflected Van Gogh’s Post-Impressionist style. The first frame that the artist had to make comprised a full painting on a canvas board, which was then painted over for each frame, until the last frame of the shot. “Basically, you paint a picture, take a photo of that. The picture is then matched with the reference image given to us. Once the supervisor offers his/her approval, you scrape and make a few changes to it [to show the next motion or movement], take a picture of it again, and so on,” says Vadalia. Each second of the film was made up of 12 frames. “Sometimes, painting one single shot would take a month. The colours had to be the same... they couldn’t change from one frame to the other, so what we would do is mix the paints and store them in plastic jars, so that they didn’t dry up.” Overall, the 94-minute film comprised 65,000 frames, with different scenes worked on by different artists. “I did around 350 paintings in total, and contributed to about 30 seconds of the film,” says Vadalia, whose paintings are visible in seven different scenes.

She has since done a three-year course on classical realism at the Grand Central Atelier, curated shows in Poland and India, and actively participated in group exhibits; including shows at Old Jaffa Museum in Tel-Aviv, ZPAP Gallery in Gdansk, and Elevanth Street Arts Gallery, New York.

Vadalia who describes oil painting as a “forgiving medium”—because it allows room for mistakes—says her style, though inspired by the lessons she learned in her classical art classes, has influences that are rooted in India. “My colour palette is inspired by miniature paintings, and the faces from Gandhara sculptures. I want to capture a lost time, where the mannerisms of people were different, as were the way they evoked emotions... maybe, it won’t be accepted by the contemporary art world, where they are looking for something modern. I don’t know.”

350

No. of paintings Vadalia made individually, contributing to about 30 seconds of Loving Vincent

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!