Endlessly cleaning kitchen counters, savouring ice-lollies, rushing to take clothes off the laundry line—art and fiction make space for the Indian homemaker’s many shades of labour and leisure

Women in Bundelkhand’s Madhopura get together to mourn as well as celebrate the death of a person who lived a full life. Pic Courtesy/Surabhi Yadav and Women at Leisure

The work of the Indian homemaker is cut out for her—even before she wakes up at the crack of dawn. The work is cyclical, repetitive and relentless, as she feeds, clothes, and takes care of her family, whether nuclear or comprising multiple generations. Some, like Delhi-based visual artist and designer Pritish Bali, recognise its Sisyphean nature; as soon as a chore is done, it must inevitably be redone. There will always be mouths to feed, kitchen counters to wipe, and clothes to dry and fold.

As part of a project titled Homemakers, realised through the Serendipity Arts Virtual Grant 2021 and displayed at India Art Fair 2022, Bali created a virtual mountain of home-cooked meals—photos of dishes and cups of tea prepared by his mother, Anu. Users who enter Homemakers’ website attempt to drag a roti icon over this mountain, as day turns to night in the background, only to find that the roti falls back to the bottom—and a new day begins. This is an artistic rendition of a dream his mother Anu had, with striking similarities to the Greek myth.

Surabhi Yadav, founder, Basanti: Women at Leisure

Surabhi Yadav, founder, Basanti: Women at Leisure

In another of Homemaker’s moving elements, the user sees the very identity of a woman change over the course of a single scroll, denoting the transformation in name and personhood after marriage. A woman named Anita Dawani becomes Neha Khemlani; Sapana Gupta becomes Payal Mahajan. In a third element of the project, Bali embarks on an overlooked, nearly impossible feat: He creates a calculator to compute the number of hours his mother spends on unpaid care work. The user can enter a start date and end date, and the widget measures the number of minutes, hours and days spent, based on an average of five hours per day.

Anu is perhaps among the few Indian homemakers whose contributions—in terms of time and effort—have been documented in such detail. As per research from IIM-A, women in the country spend 7.2 hours on domestic work, nearly thrice as much as men do. And if this labour were to be monetised, it would account for 7.5 per cent of India’s GDP, says a State Bank of India report from 2023. “I have had innumerable conversations with homemakers who came and engaged with the project [at the India Art Fair and Serendipity Arts Festival] and a lot of them were very enthusiastic to claim their daily hours of work. It was slightly amusing at times when they’d show the number to their partners and children,” Bali says in reflection. He is among a growing group of creative professionals whose works document the many facets of the average homemaker’s life, in urban and rural India. Through conversations with visual artists, writers and photographers, mid-day finds depictions of their labour, their complexities, and their urge to find a sense of identity and leisure.

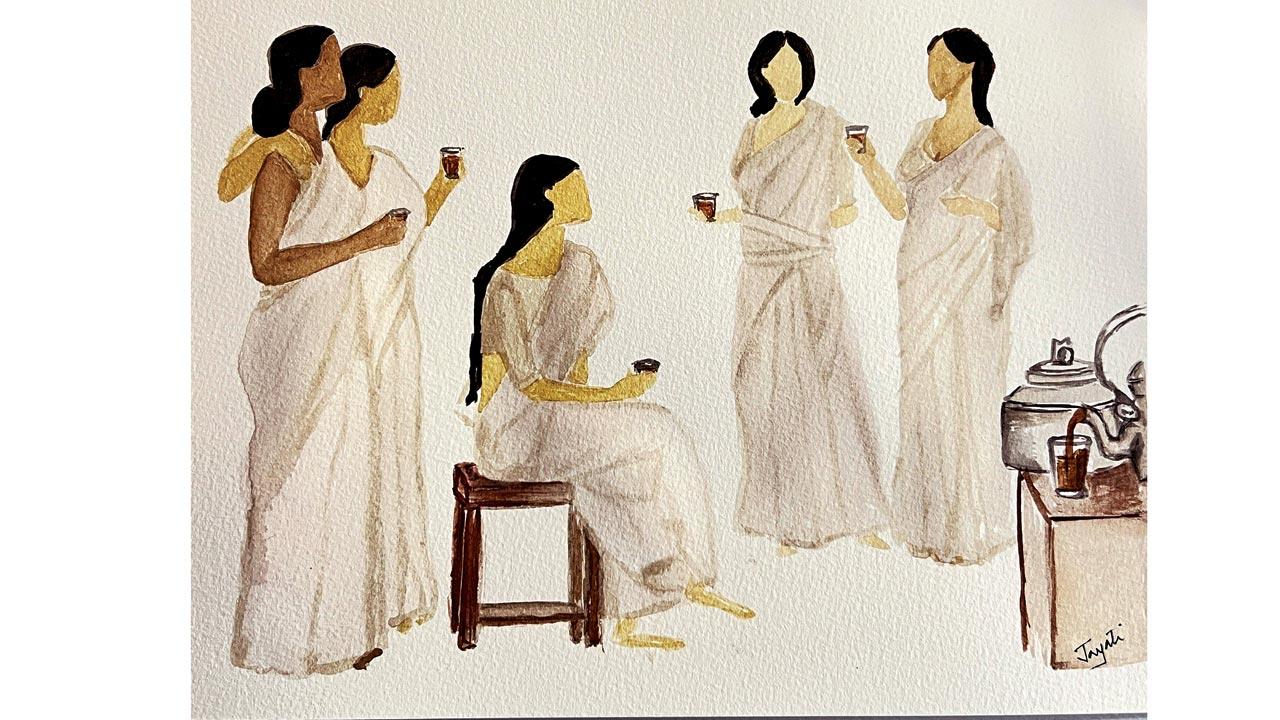

Jayati Bose’s watercolour works of leisure-filled scenes depict women living life on their own terms. Pic Courtesy/Jayati Bose

Jayati Bose’s watercolour works of leisure-filled scenes depict women living life on their own terms. Pic Courtesy/Jayati Bose

On the walls of Chemould Prescott Road, and across its expanse, hang old sarees carrying images of women weaving, sweeping, caring for their children, and savouring iced lollies, all part of printmaker Jayeeta Chatterjee’s solo show. Moments from their existence that would not otherwise be visible to the outside world are brought to life through large block print compositions, the Nakshi Kantha quilting technique, and traditional stitches. What makes these artworks all the more special is that the sarees used as canvases by Chatterjee belong to the women she has depicted.

The Kala Bhavana-trained artist’s interest in the inner world of women’s domesticity took root when she was a Master’s student at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. She found herself reflecting on the dynamics of femininity, and the mental well-being of homemakers, as well as their daily routines.

Jayati Bose

Jayati Bose

The works in the ongoing show An Eye Inside are crucially multilayered: one block-printed image underscores the image printed on the other side of the cloth, evoking the image of an ever-working, ever-busy woman at home. “Each layer symbolises various emotions, struggles, and moments experienced by the women. By intertwining these layers, I seek to evoke a sense of complexity within simplicity, reflecting the intricate realities of a homemaker’s life,” says Chatterjee.

Just as Chatterjee brings us closer to the subjects of her artworks, Bali clarifies that his mother Anu is not a muse or inspiration, but rather a collaborator on Homemakers. “I also thought of this collaboration concerning the whole idea of ‘care work’ and the relationship between a mother and a son or any other familial relationship for that matter. The project proposal also included remuneration for the meals cooked during the project period just because I thought ‘Why not?’”

Bali shares.

Jayeeta Chatterjee’s detailed block print and embroidered works give the viewer a multilayered look into women’s domestic politics. Pic/Sameer Markande

Jayeeta Chatterjee’s detailed block print and embroidered works give the viewer a multilayered look into women’s domestic politics. Pic/Sameer Markande

As she sat at her desk to write Frenny and Other Women You Have Met, Soma Bose was certain that she wanted to celebrate homemakers who are offered no accolades or recognition. Her reasons were personal: In the years after she got married, she was a homemaker though she did occasionally dabble in entrepreneurship. “When my son was in school, his friends would quiz him about what I did for a living,” Soma says, “He’d say, ‘My mother is a writer.’ At the time, I wasn’t an author—I did some freelance projects for production companies, but that’s how my son perceived and described me.”

The Noida-based writer imbues her characters with rich inner lives; consider newly-married Shreyasi whose life is given a new purpose, when her music teacher—having lost crucial memories to dementia—relies on her to re-learns melodies. Or the unusual friendship between grey-haired stationery shop owner Frenny and young philanthropist Sucharita. “I drew inspiration from the many housewives I crossed paths with. Perhaps they would not be considered successful in the conventional sense, but they were all strong figures in their own way,” she says.

Pritish and Anu Bali’s project Homemakers explores women’s identities, the value of their care work and the endless cycle of domestic duties. Pic Courtesy/Pritish Bali

Pritish and Anu Bali’s project Homemakers explores women’s identities, the value of their care work and the endless cycle of domestic duties. Pic Courtesy/Pritish Bali

If Soma’s characters are recognisable to and invoke empathy in readers, the protagonist Shalini’s mother in Madhuri Vijay’s The Far Field—which won the 2019 JCB Prize for Literature—is the embodiment of atypicality. Termed a strong woman by those relatives and acquaintances who did not intend for it to be a compliment, the mother scared shopkeepers, joked about slaying her neighbours’ naughty children, and threateningly flirted back with men who eyed her. “I am not one of those bored housewives you see every day who keeps on buying new things because she doesn’t know what to do with herself. And if you think I am one of them, well, you’re not as intelligent as you seem,” Shalini’s mother declares to a travelling salesman she falls for.

Dressed in graceful pearl and ivory-hued sarees, the subjects of Jayati Bose’s paintings are faceless, and yet, the painter and sculptor is able to convey a distinct sense of free-spirited joy. In Boondein, from Jayati’s ongoing series Women at Leisure, these saree-clad women rush to the roof of their friend’s home to take clothes off the laundry line as dark clouds gather in the sky. In other works, they kick around a football; dance to the beats of a tabla, cycle, and take in the winter sun together. “My women, like me, do what they wish. They gather their friends and have fun when they want to, on their own terms. That’s what leisure means to me,” she says.

Jayati, whose works are on display at Ahmedabad’s Bougainvillea gallery as part of an ongoing solo show, says that her conception of leisure was shaped by her upbringing and the dynamics of her own home, where she and her husband distribute chores equitably. “My women are an extension of me and my memories. I have been brought up to look at the world through a lens of equality. I have seen the ladies of my family do the same—yes, they performed their family duties, but they never let go of their identities. They had their moments in the sun, they let their hair down and had fun,” Jayati says. The show’s curator and interior architect Kunal Shah observes that the artist “has ingeniously used the female gaze in her works.”

The female gaze is also palpably evident in Basanti: Women at Leisure, a seven-year-old multimedia repository by Surabhi Yadav which documents Indian women resting, making time for themselves and finding pockets of leisure. The Instagram-first project, which began with her own documentation endeavours, evolved into a crowd-sourced effort two years ago, as people across the country submitted photographs and videos. A number of the project’s posts feature homemakers and stay-at-home mums and grandmums—reading the newspaper, spending an evening at the sea, playing a solitary game of cards.

Speaking to mid-day over the phone from Himachal Pradesh’s Kandbari village, Yadav says that when she showed her subjects the photographs, they’d let out a

giggle. “Always, always, there’d be the sound of laughter… of shyness but also amusement, at being captured while doing something seemingly irrelevant. It was unusual for them to be photographed candidly,” she says.

The conversation that followed was an eye-opener: When the University of California, Berkeley alumna would quiz them about what they did in their free time, they’d respond incredulously: “Who has free time?” “Many women also take pride in not being free… The idea that people have carefree, unrestrained time is so unbelievable to most,” she notes.

Though leisure activities are monetised and formalised in urban settings, women in cities are still held back by the demands of housework and child care. Yadav notes that through their proximity to nature and the continuing importance of certain grooming and domestic practices, homemakers in rural India may have easier access to leisure than their urban counterparts. “Oiling one’s hair, tying it into a plait—simple tasks like this are performed lovingly and unhurriedly… Wherever work and labour are gendered, leisure will also be gendered,” Yadav signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!