While ‘ideal Bambai’ might seem like a myth, we got the dreamers and believers to imagine a fresh blueprint for the city they call home, thinking up revitalising solutions that can make it more liveable and loveable

Images Courtesy/Prathima Manohar

By Mitali Parekh, Jane Borges, Yusra Husain, Heena Khandelwal and Nidhi Lodaya

Let’s reimagine BKC as a mixed-use place with a 24x7 urban environment

Working towards gender mainstreaming through urban development plans

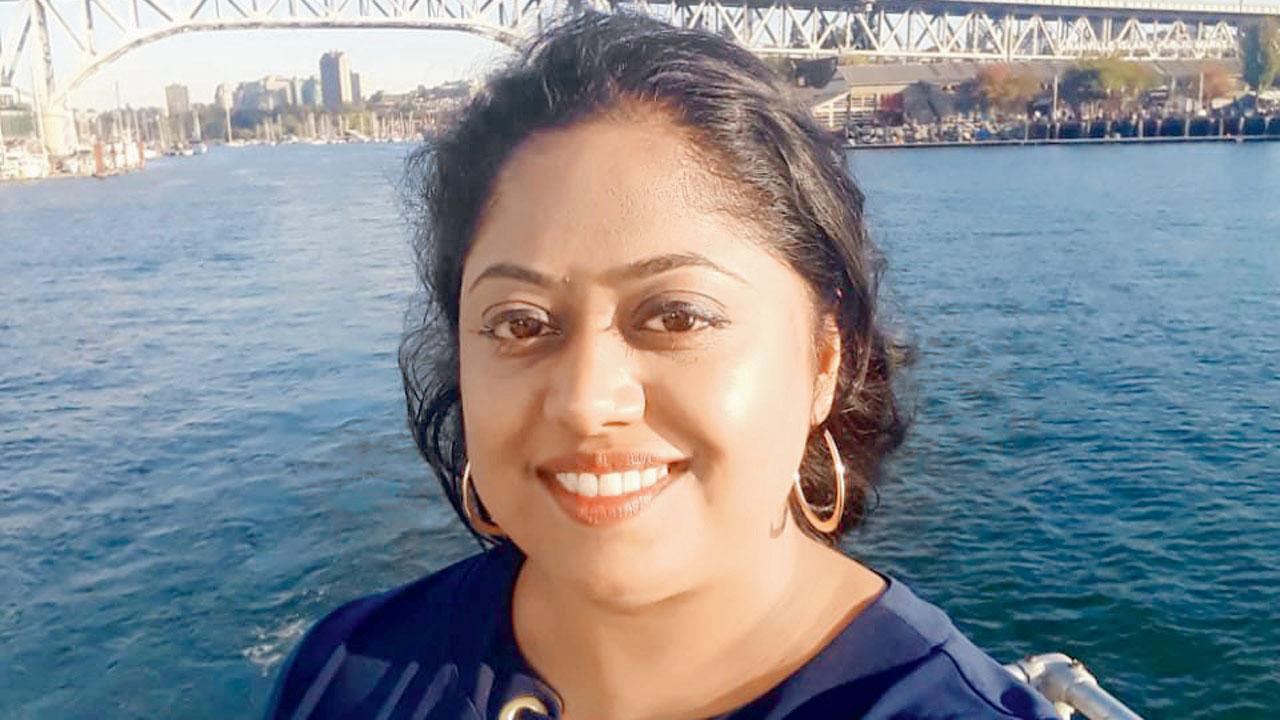

Vision Creator: Prathima Manohar, urbanist, specialist architect in place activation and co-founder, PlaceXplore

All women, says Prathima Manohar, are hyper aware of the way they experience the spaces that they inhabit. As a 22-year-old architect, when Manohar moved from Bengaluru to work in Mumbai, she remembers finding the city “liberating”. But early on in her career, while working on a video documentary on Dharavi, she realised how young girls living there would plan their day, based on access to toilets. “I grew up in a post-feminist era, where I did not face any discrimination. But that did not mean my experience was a shared one,” she says. Later, when collaborating with ElsaMarie D’Silva, founder of Red Dot Foundation and president of Red Dot Foundation Global, (Safecity), for the Safecity app, Manohar sensed the urgency of creating an inclusive, women-first city. The platform collects and analyses crowdsourced, anonymous reports of sexual violence, identifying patterns and key insights. “The data that emerged showed hotspots of violence. And that made a big difference, indicating a parallel between the kind of infra being designed and where we were noticing more violence,” she shares.

According to Manohar, “the way a city is designed affects women’s freedom and access. It can deter or empower women from going to school, to being an entrepreneur”. “Real economic advancement will remain a pipe dream unless we empower women. The famous report by McKinsey Global Institute titled ‘Power of parity’ had highlighted how the world can add $28 trillion or 26 per cent of GDP by 2025 if women participate in the economy like men do today. The right model of urban development can catalyse this growth,” she says, adding that a city that is inclusive and comfortable for women, children, and the elderly is a great city for everyone. “Currently, most of these ideas are just pilots... it has to be more mainstream and everywhere. And one of the ways to get this done, is to have the community demand it.”

Manohar says that Bandra Kurla Complex, which is now the main business hub in Mumbai, currently has the most potential to be designed inclusively. “It’s a single-use place. You go there in the morning, and return from there by evening,” she says, “I would like to reimagine it as a mixed-use place with a 24x7 urban environment where girls and women from all strata of society thrive, feel safe and secure at all times of the day.”

Manohar visualises a built environment that has human scale architecture activated with retail, cafés or streets with hawkers that ensures “eyes on the street” that offer natural surveillance. At the moment, most parts fall silent and dark once the commercial centres have shuttered. “I even envision adding a diversity of social services programming within building spaces to enable a more caring city like childcare services in public spaces/transit, gyms, kindergartens, community health clinics, community markets, social parks for play dates and other caregiving services to make it easier for a young mother to work. Additionally, I’d want to see this neighbourhood grow livelier by adding ‘made in local’ market places for art, handcrafted goods and food pop-ups, that can promote local economic growth and women’s microbusinesses. I would love to see more women in the community and public work force like traffic police, security guards and even taxi/ auto drivers.” And since mobility is the fulcrum which allows or deters women’s participation in the economy, she hopes that someday “BKC can offer end-to-end mobility and comfortable last mile connectivity”.

What if slumdwellers self-financed construction of their homes with NGOs through affordable EMI model?

Equal city

Exploring architectural practices that bridge

social inequalities

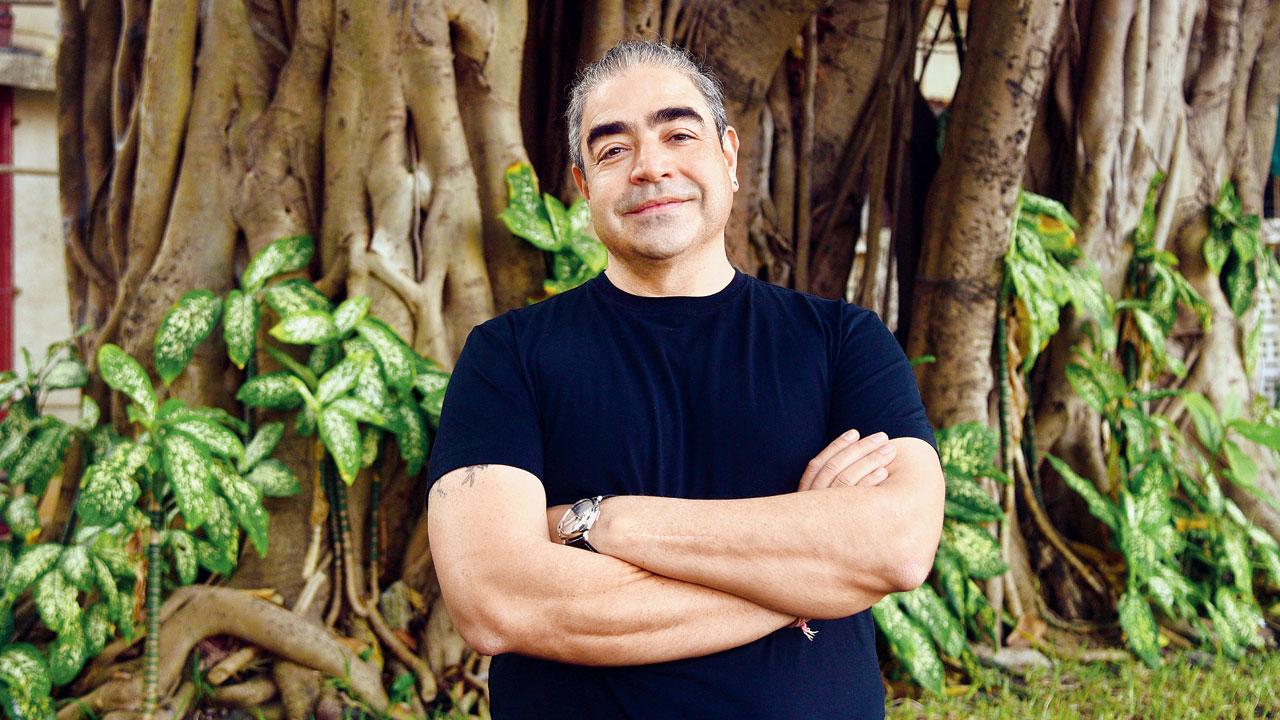

Vision Creator: Rahul Kadri, Principal architect-partner, IMK Architects

For Rahul Kadri, designing a socially equal city has less to do with blurring the distinction between the rich and poor, and more with equalising how they co-exist within the same space. “What is critical is that public spaces be made open and accessible to all, and the city be made pedestrian-friendly, where everything is just a 15 minute-walk away,” he shares. The idea might seem utopian, but Kadri says small design changes can go a long way.

“[At our firm] We design a lot of townships, university buildings, hospitals, and schools. In all these projects, we are focused on two things, incorporating nature and enhancing personal relationships,” he says, explaining that when it comes to nature, including courtyards, balconies, and multiple gardens in the design is key. “Also, if there’s a choice between going highrise or lowrise, we always prefer the latter, so that we stay within the tree line, and the structure is not too far from the ground.” Built structures, says Kadri, should also be designed in a way that they do not alienate people, but bring them together.

“For example, if we are designing a university campus, we will try and have at least one main pedestrian street, which also serves as a promenade for everyone to walk down daily. This way, there’s scope for people to run into each other, and often. It helps increase the probability of meeting the same people again, and helps forge friendships,” he explains. In residential spaces, he says, they make sure that at least hundred families share a common open space. “We don’t believe in having one large space, because then it becomes too impersonal, and you don’t get to know your neighbours.”

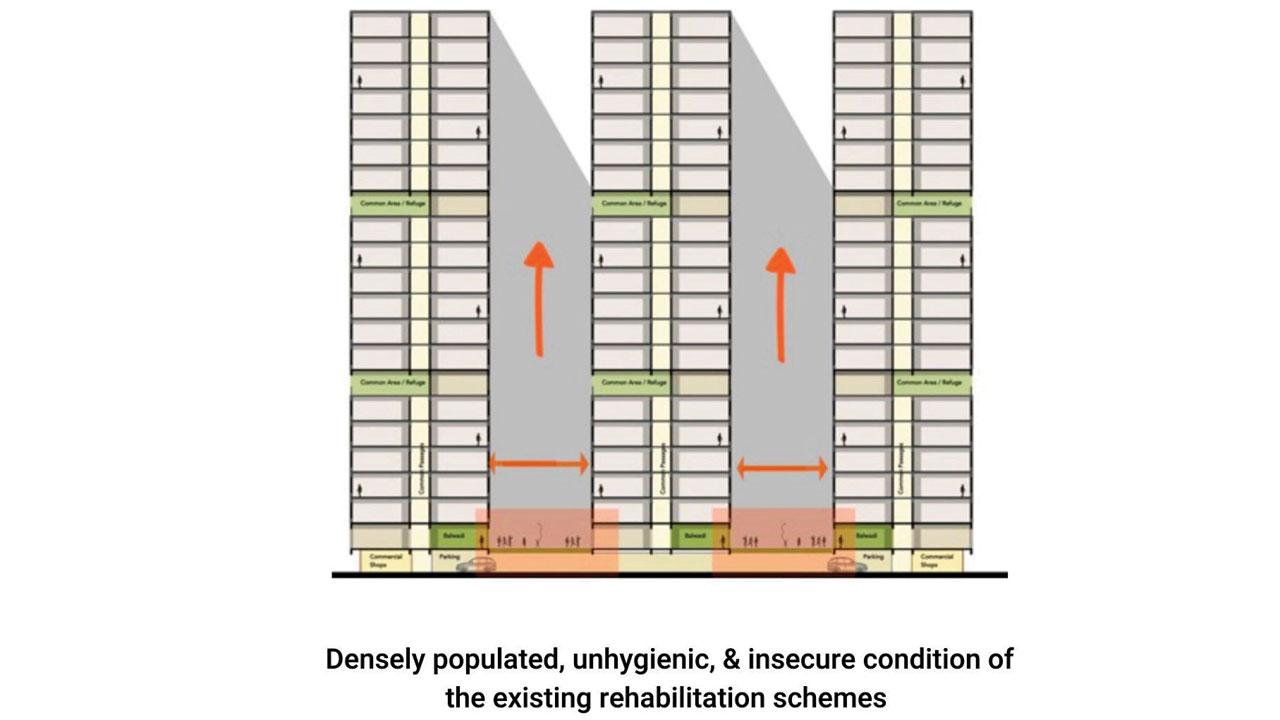

One of Kadri’s pursuits has been to ensure the dignity of living to all. And, he believes that the slums of Mumbai have provided a rare opportunity for administrators and designers to rethink how this can be made possible. “Fifty per cent of people living in Mumbai, reside in slums. While the slum conditions are horrible, the government’s solution is the slum rehabilitation scheme [initiated by the Slum Rehabilitation Authority].” As part of the scheme, a developer has been made in-charge to provide a chunk of free houses, and others for sale at subsidised rates.

“But the slums are already one of the densest developments there are in the city, and if the developer is given 60 to 70 per cent of the land for sale, the slumdwellers will get squeezed into a development which is three times denser than what they already have. So under the guise of free housing, you are actually taking away their light, ventilation, their health and privacy. Right now, all of these basic needs are being condoned. It’s like saying, it’s not necessary, because you are poor.”

Kadri instead suggests the community-led redevelopment of slums, where slumdwellers self-finance the construction of their own homes with the help of NGOs through an affordable EMI model. “You can build multi-storey houses which are not 20 or 30 floors, but six to eight floors, with more open space. And, everyone has a decent home.”

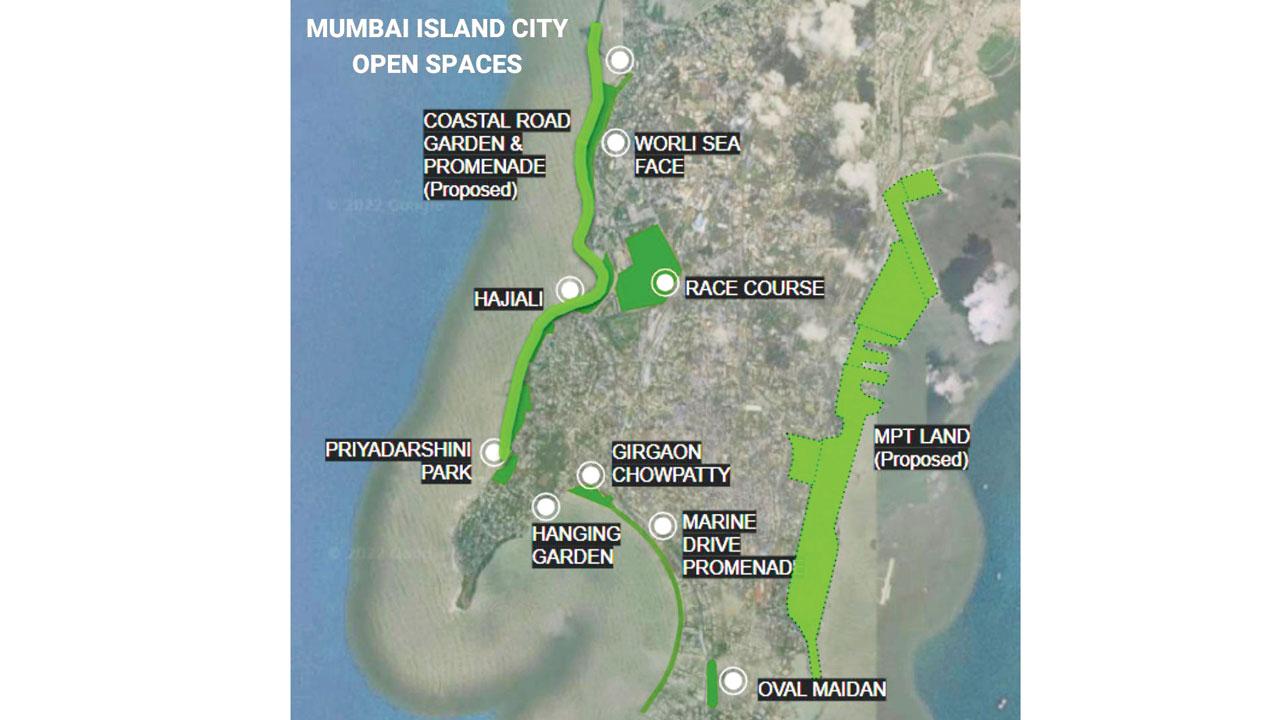

He also feels that Mumbai now needs more gardens that bring people from all walks of life together. “At present, there are two parcels of land—200 acres on the coastal road, including the promenade, and 1,800 acres on the east coast—which if developed, can give the city 2,000 acres of gardens. If that happens, one million people can enjoy open spaces. There is an opportunity, and this is our last chance.”

Will we take it?

Celebrate the coming together of people from varied backgrounds

Happy at work city

Building workplaces that foster diversity and inclusiveness

Vision Creator: Malcolm Mistry, director, Ushta Te HR consultancy

What’s the secret to keeping employees happy and productive? Malcolm Mistry believes the answer is in making them feel they belong.

Most companies, he says, organise one-day diversity programmes, and then pat their own backs for being inclusive. But such tokenism is hardly enough. “It’s a culture which has to be developed by the organisation over a period of time. They need to celebrate, foster and encourage the coming together of people from varied backgrounds and perspectives, and create an environment where individuals feel valued and good about the role they play. When employees develop a sense of belonging, the organisation also does well. It’s a win-win situation.”

Building infrastructure facilities such as prayer rooms and gender neutral washrooms are great, but “making a person feel safe and secure to use these washrooms is what matters”. “They need to feel comfortable, respected, and be assured that they are not being judged.”

Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

The need for a healthy work-life balance is also crucial. “The employer should sit down and listen to their employees to find out the challenges they face.” When it comes to Mumbai, Mistry says the commute time can take a toll. “It [Mumbai] is not planned like an integrated city such as Calgary in Canada, where you can walk to work.” In this situation, “organisations should think about a hybrid model, which does not affect productivity. Another option could be flexible timings where employees can beat the traffic. The pandemic has made us realise that this is all possible.”

Mistry says city administrators should shoulder the responsibility of keeping the work force happy. For instance, they could consider including more recreational spaces, where individuals or groups can have team building activities. “A good city is one which has great employment opportunities, work-life balance, affordable housing, integrated planning and a high living index to make it a liveable city.”

Normalise animals being part of our surroundings

Empathetic City

Creating caring communities that acknowledge animal protection for human welfare

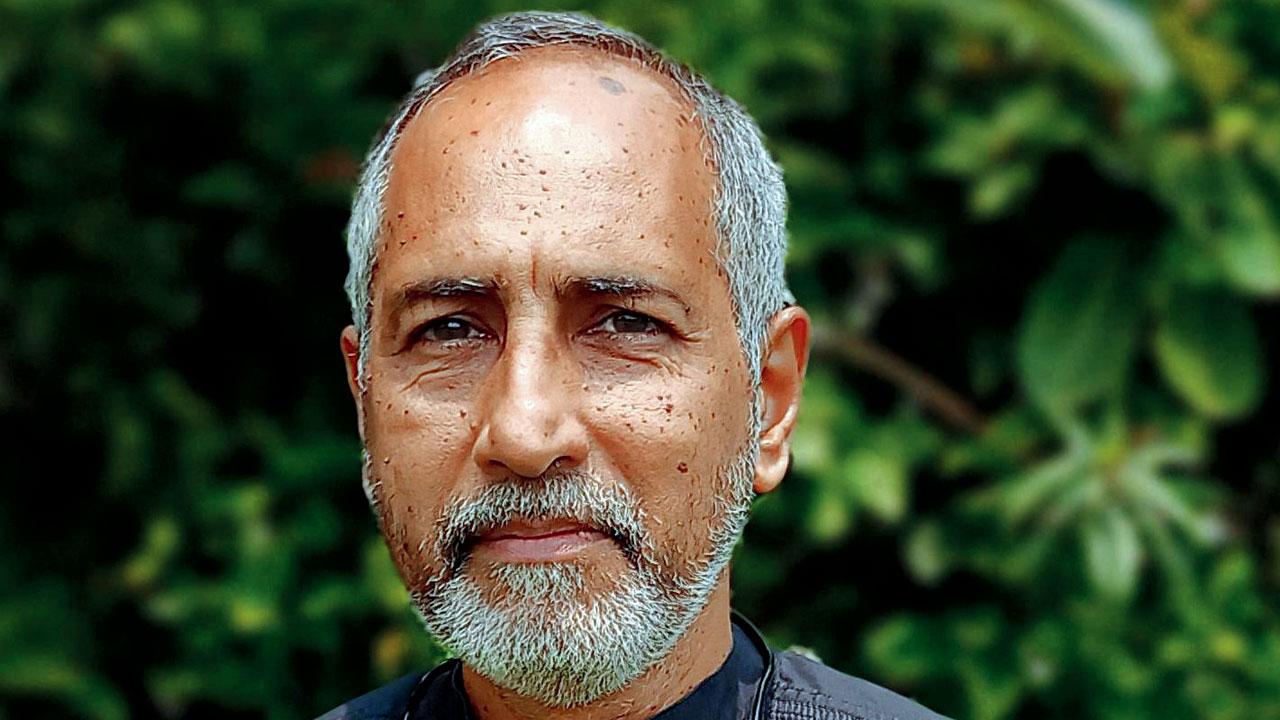

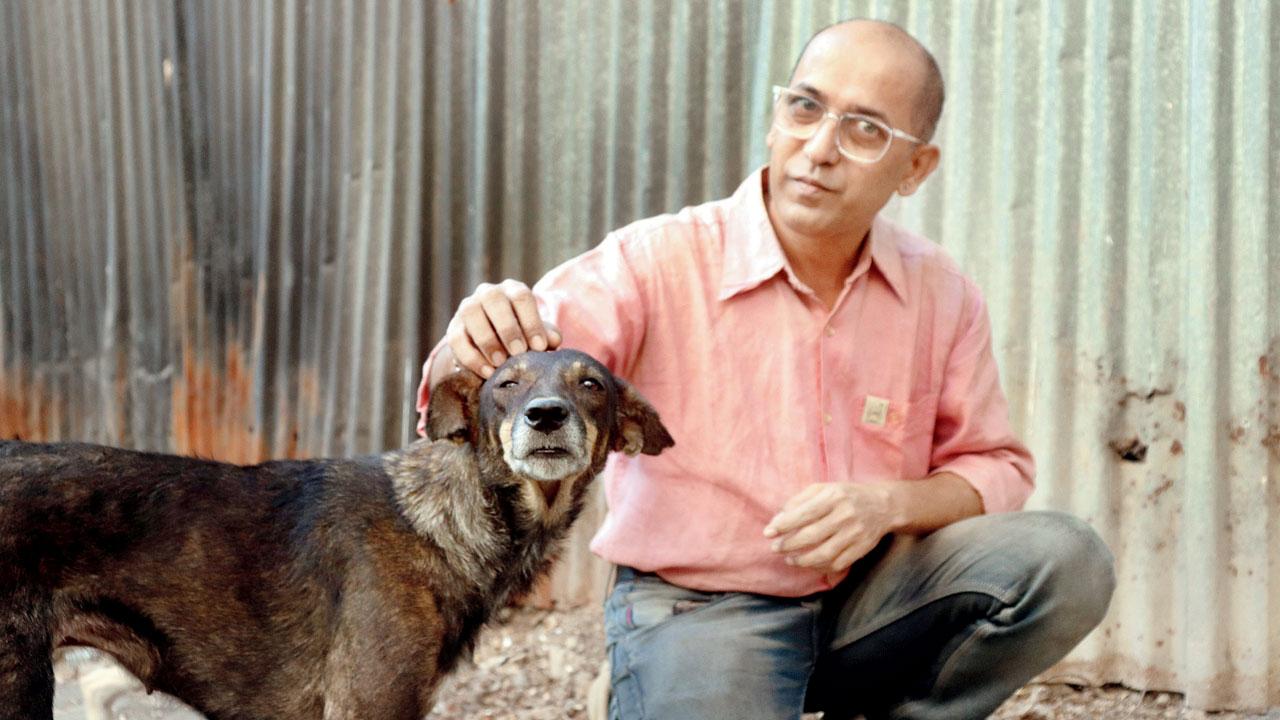

Vision Creator: Anand Pendharkar, Wildlife Biologist, SPROUTS Environment Trust

All talk of turning the city more empathetic towards animals starts with the knowledge that the BMC is the richest municipal body in the world. Governance Now had reported that the civic body had an estimated income of Rs 27,811 crore in FY 2021-22. So it can’t be hard to find a few paise to lay down infrastructure that would help lower the population of stray animals roaming the city, attend to injuries and inject information about them into the education system.

“We have no official [state or city] rescue or animal welfare body,” says Anand Pendharkar, adding, “Rescue and sterilisation centres in every ward would help control the population of stray animals, but more importantly, the costs involved which can be a deterrent to animal lovers/activists [Many sterilisation centres are placed out of the city, incurring transport costs]. Vets should be encouraged to give a few hours of their time every week, which will lower costs.”

Grass root work would have to be education about urban wildlife and stray animals, sowed into school curricula through interactions with snake/bird/ dog/cat rescuers, sniffer dogs or other service animals, and companion animals so that “children learn that an animal is not a stuffed toy with life.” This will also help them learn the body language of the animals, and the approach to adopt to lower friction between our species. “First Aid responses to urban wildlife, such as finding a fledgling that has fallen out of the nest, injured fruit bats, kites, squirrels or snakes should also be taught in schools or residential communities,” says Pendharkar. “Numbers for rescuers should be circulated in neighbourhoods, just as we do for the fire brigade and ambulance.”

Large strides in co-habitation can be made by creating win-win situations. “Orphanages and old age homes should be together for each to benefit from the other, and dogs and cats can be adopted or allowed to live within the premises too,” says the Andheri resident, whose home office has visiting squirrels and birds. “Workplaces can also adopt this and have segregated, special areas for interaction with the office cat or dog. This would serve as emotional support, without disturbing other employees. [mid-day’s suggestion: Get employees to play with or walk the dog instead of taking a smoke break.] In the same way, kite-flying and bursting crackers should be done in designated community areas so that birds and other fauna are not harmed.”

When Pendharkar taught at The Doon School in Uttarakhand, he absorbed lessons on normalising (and not apologising) for the presence and actions of animals in the human environment. “A stray dog could wander on stage during Founder’s Day or some other function, and the principal would just laugh it off saying, ‘You [the chief guests] have your security, and this is ours’ or ‘And these [the dogs/cats] are the other chief guests’. Once, they also started mating on stage and the principal just said, “We are getting a live biology lesson”. Pendharkar insists we normalise animal presence as we should masturbation, breast feeding and menstruation.

Dogs and cats aside, we share the city with invisible (until an “annoyance”) wildlife: fruit bats, kites, snakes, squirrels and other animals. Community and civic efforts here would enrich everyone’s lives. “Planting fruit trees, instead of ornamental and shade-giving trees, is the most obvious thing I can think of,” says Pendharkar. “This will provide food for humans and squirrels, birds, and encourage eco-systems with butterflies and other insects.” Another winning idea is bee boxes in communities, which will help cross-pollination.

Not to say all things furry must be cuddled. “I hear currently, the population of rats is nine per human in the city,” he says, “So we are sitting on the probability of the outbreak of another zoonotic disease such as COVID-19. We need garbage management to contain the population of rats, cats and dogs. Even leopards stray into human habitats to hunt the animals that eat out of dumpsters.”

FOBs aren’t solution, but the problem

Pedestrian-friendly city

Proposing walking as a transportation mode

Vision Creator: Geetam Tiwari, TRIPP Chair Professor, Department of Civil Engineering at IIT, New Delhi

Imagine a city where people prefer walking to the nearest bus stop or railway station, instead of taking an auto or taxi. This is the vision that professor and head of Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Centre, Delhi, Geetam Tiwari has for Mumbai, which has the largest share of pedestrians. Unfortunately, they also make up for a big chunk of the road traffic fatalities in the city, something that Tiwari, who is joint faculty at the Department of Civil Engineering at IIT Delhi, finds unacceptable.

The problem, she says, is that the width of pedestrian paths has been reduced to make space for wider motorised traffic lanes. “Many pedestrians are forced to walk on these lanes, exposing them to high speed traffic. The available pedestrian paths are often not continuous, which increases the risk of falling and getting injured, especially when used by the elderly,” says Tiwari.

While authorities claim that they are building foot overbridges (FOB) for pedestrians, the truth, she says, is that this infra is mostly constructed to provide uninterrupted movement to cars and motorised two-wheelers. “Pedestrians are being forced to walk extra or climb stairs, which is time consuming and can be difficult if you are carrying groceries or are an elderly person or pregnant.” Tiwari points to research studies, which have shown that FOBs and subways are neither comfortable nor convenient for most pedestrians. “The usage of such facilities remains low, and often the area near FOBs and flyovers become crash-prone spots because pedestrians crossing the road are exposed to high speed motorised traffic,” she says, adding that roads, streets and FOBs should be designed in such a way that they meet the need of pedestrians, encouraging them to adopt walking as a preferred mode of choice, especially for short distances.

A PhD holder in Transport Planning and Policy from the University of Illinois, Chicago, Tiwari says a strong policy framework is required to make Mumbai walkable. “A mandatory city-level policy guiding all the wards to prepare a road map for being pedestrian-friendly [sustainable urban transport compliance] is necessary,” she says, adding, “The public works department and municipalities have to induct designers and planners to work closely with civil engineers to execute this. Compliance to current street design guidelines have to be made mandatory by law, and traffic enforcement agencies have to be guided to make this possible. City administration has to create a monitoring mechanism to evaluate the progress of implementing walkability guidelines.”

Some of the specific interventions that can be implemented with immediate effect in the city include “restricting free left turns at signalised intersections, speed compliance of motorised vehicles on all roads—50 kmph on arterial roads, 30 kmph on all other roads and 15-20 kmph zones near schools and hospitals—and better enforcement through red light camera and police monitoring”.

“Intersections, areas near bus stops, train and metro stations require specific treatments to make them pedestrian-friendly. While use of speed cameras to monitor speeding vehicles may be employed, introducing specific design changes such as speed tables, change in road texture, wide footpaths, short delays for pedestrians at signalised intersections are well-known strategies that should be implemented.” At the ward level, she suggests walkability audits and a master plan for implementing specific interventions in a phased manner.

Decentralisation of solid waste management holds the answer

Waste-free city

Training communities to get efficient at plastic waste and garbage disposal

Vision Creator: Rishi Aggarwal, environment protection activist and founder, Mumbai Sustainability Centre that runs Safai Bank

Does waste-free Mumbai seem like a utopian dream? For Rishi Aggarwal, it is an achievable proposition especially given the abundant resources that the city’s civic body is blessed with. He dreams of a Mumbai with no visible sign of uncollected waste, burning garbage and dumping of debris in nullahs and rivers.

Illustration/Uday Mohite

This, he says, can be achieved if we decentralise waste management and attract participation from both, administration as well as citizens. “This would mean that the city would have an adequate number of dry waste collection and management centres at the ward level,” says Aggarwal, adding that the first step in this process is to segregate waste at home into three categories—wet, dry and domestic hazardous waste. The last includes sanitary pads, pesticide containers, sharp objects, and medical waste like gauze, bandaids and syringes.

“Residential buildings should be encouraged to compost food waste, and should be incentivised with benefits in say, property tax,” he shares, adding that this decentralisation of waste management would lead to a reduction in garbage going to choked and overflowing landfills where often the residents and authorities are at loggerheads. “Over a period of time,” says Aggarwal, “if we are able to turn the waste going there to zero, we can turn this land into public places. Consider this—Deonar dumping ground is spread over 320 acres. The Oval Maidan is just 22 acres. Imagine how much space this can open up for utilisation, whether creating recreational areas and football grounds or being used for low income housing projects.”

Aggarwal also suggests creating a waste to wealth paradigm, where food waste is converted into compost and biogas, and dry waste, as much as possible, is sent for recycling. “Ukraine’s energy crisis has strengthened the need to convert food waste into bio-CNG and have BEST buses and other vehicles run on it. As of now, unfortunately, we are transporting all of it to Deonar and Kanjur, which is a nuisance,” he says, adding that another type of waste that poses a huge problem to a city like Mumbai is construction and debris (CND) waste.

“Years ago, Mumbai was a pioneer in setting an example of how debris can be converted into paver blocks and bricks, which could be ploughed back into construction. Right now, it’s illegally dumped and is choking mangroves and water systems.” Lastly, he suggests that the state take pride in waste management, training workers, providing them with enough safety gear and ensuring that their contribution to society is valued and fairly compensated. “All of this is doable. What’s proving to be a hurdle is red tapism and the involvement of politicians.”

Police and govt officials should be counselled on trans rights

Inclusive city

Integrating marginalised genders seamlessly into the mainstream

Vision Creator: Dr Pawan Yadav, Maharashtra’s first transgender lawyer

The National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) judgment by the Supreme Court in 2014 led to the recognition of transgender people as the third gender. Following this, we also witnessed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, which provides protection to their rights and welfare. “As per this act,” says Advocate Dr Pawan Yadav, “every state is supposed to have a transgender welfare board.”

According to reports, The Maharashtra Transgender Welfare Board was set up in 2019, but Yadav believes that implementation is still wanting. She believes that if the board functions in earnest, sufficient funds will be released to help secure the fundamental rights of the LGBTQiA+ community. “If a woman is harassed, she can file an FIR at a police station; trans women don’t enjoy the same rights; the police will be reluctant to file the complaint,” she claims.

Pic/Anurag Ahire

Yadav would like every police station across the state to set up a group that helps raise awareness about transgender people. “In fact, not just the police, all government employees must be counselled on the challenges and rights of trans people. When we visit an office with a query or grievance, we hear them say, ‘Kinnar aagaye’ [transgender persons have come] and we see a sense of fear.

Sitting across a table with them as equals will take care of this.” Yadav is the first transgender advocate to practice in the state and is president of Saarthi Foundation, a non-profit that uplifts the underprivileged in the health and education sector. The 26-year-old has a doctorate in social welfare from the United Nation’s Open University for her work on the trans community throughout the state.

Yadav has drafted a petition to the BEST undertaking, requesting special reserved seats for trans passengers like there are for women and the specially abled. Same with local trains. They are treated with disdain even when they buy tickets.

It’s been an uphill task and Yadav admits that she hasn’t always been successful. She hopes that the government will consider providing stalls and space to transgender persons to run street food stalls. “Instead of begging at signals, we could earn money through legitimate work with a little help from the authorities , and support from the people who frequent the stalls.”

Mumbai should have a biogas sewage system

Permaculture-happy city

Creating an innovative framework for practical ways to pull off ecologically harmonious ways of living

Vision Creator: Simrit Malhi, regenerative farming and permaculture practitioner

For many world problems—hunger, pollution, degradation of the environment, inflation, human isolation—permaculture can provide an atlas of solutions. The farming and community-building discipline allows for the growth and nurturing of agricultural ecosystems in a self-sufficient and sustainable way, so that each discipline supports another.

Simply put: You grow what you eat, compost what you don’t eat, catch and conserve water, use the water you have used to water the food you grow to eat. To our child heart’s delight, you can use human waste as fuel to cook (grow-eat-excrete-cook).

It recreates naturally occurring, interdependent patterns of resilience, productivity and sustainability, and is based on 12 principles: observe and interact; catch and store energy; obtain a yield; apply self-regulation and accept feedback; use and value renewable resources and services; produce no waste; design from patterns to details; integrate rather than segregate. All principles can be applied to the self as much as to the land, and come from ecological pioneers, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren.

Simrit Malhi teaches permaculture, and lives in a house built using natural materials in the middle of a food forest she planted in the Palani Hills of Tamil Nadu. “The simplest way to apply these principles to a city like Mumbai,” says the farmer who transplanted from South Mumbai, “is to plant fruit trees along the roads. Grow some little plant, anything you eat—mint, lemongrass, coriander, kadipatta—in your window sill.”

Her larger ambitions include natural, packed mud for pavements, instead of cement—to allow seepage of water to raise the water table, and let invisible biodiversity of bacteria and insects to thrive. More drains that route rainwater to public gardens or storage systems in housing societies and civic water tanks. “A biogas sewage system for the city, with the slurry running to the trees at Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and free gas for city folk,” she says. Small scale wind turbines in wind tunnels forming naturally between buildings can generate power, as do solar panels.

Her vision includes every building society growing its own food: An organised compost system must be developed for each building, and permits to new buildings should be issued only if a certain amount of area is assigned for growing food. Roofs can become farms, and public gardens can become bhaji-markets for a few hours every weekend to grow ‘eat local’ bragging rights. Her highest ambition to reduce sound and air pollution is to charge car tax to enter inner city limits and give only-pedestrian access to dense zones of the city after 6 pm.

‘Koli wisdom should be tapped’

Door-to-the-sea city

Preserving and nurturing mangroves and fishing villagesVision Creator:

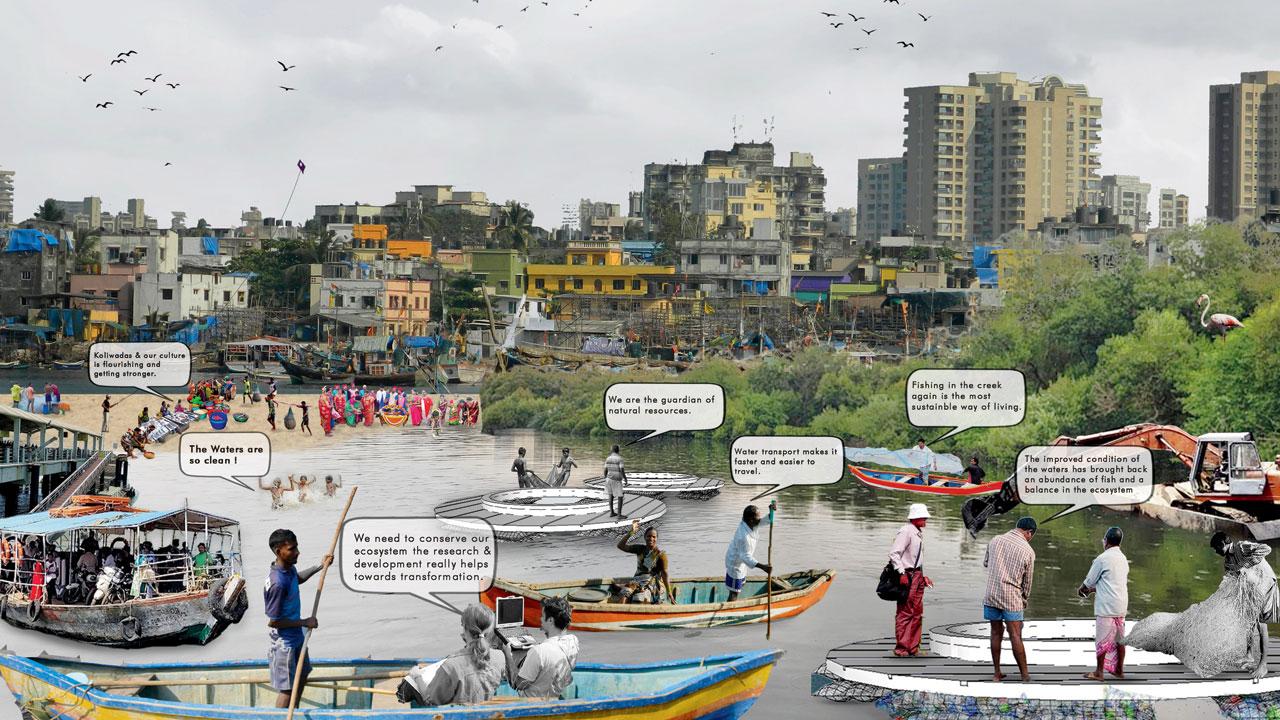

Jai and Ketaki Bhadgaonkar, Architects, Urban designers, Co-Founders Bombay61

Who should know more about their home? Those who dwell in it, or those who look at it from the outside, as mere tourists visiting in good times and good weather. Well, the answer is simple and wouldn’t evade anyone... the inhabitants, of course. The same then goes for strengthening the coasts of Mumbai. And urban designers and architects Jai and Ketaki Bhadgaonkar believe when it comes to the city’s coast, the Kolis should be approached.

“For more than 600 years, Mumbai’s indigenous Koli community has lived along the island city’s coastline,” the Bhadgaonkars say. “They have always had a close bond with the water ecosystems, which has made it integral to their way of life and culture. This relationship was severely hampered after colonisation. The authorities took control of the ecosystems under the guise of urban development and now only 39 Koliwadas remain extant. Mumbai has only ever been seen by planners from the ‘land’ aspect ignoring the importance of the surrounding ecosystems,” they add.

It is this bond of the Kolis with the coastal ecosystem, peppered with their cultural traditions and indigenous knowledge, that the Bhadgaonkars say should be tapped into. “We believe it is time for the planners to change their focus from land to waters because we are a ‘sea city’.”

Sharing their vision with us, they say, “The Mumbai that we picture is deeply committed to protecting the city’s natural systems while foregrounding the local knowledge of the communities. The creeks and other water systems must be cleaned, respected, and unclogged like the body’s clogged arteries. And using the indigenous method of fish nets to catch the plastic and waste thrown in the sea is one such solution for it.” Back in June, urban solutions think tank Bombay 61 Studio (co-founded by the Bhadgaonkars), youth-led collective Ministry of Mumbai’s Magic (MMM), and research entity Tapestry, along with the Kolis of Versova had led a pilot project, New Catch in Town, collecting 500 kg of trash from the Kavtya Khadi in Versova. The project had tapped into the Koli wisdom of using traditional fishing nets to entrap waste in the creek.

“Besides tackling the creek’s waste and strictly controlling the pollutants that are released in water, we also need a good solid waste management system,” says Ketaki. “Wetlands can be built, through which plant roots absorb pollutants and cut down on sewage water, and fishing infrastructure should be developed as a means of livelihood for the community,” she adds.

The architects opine that the Koliwadas require unique “local area planning” organisations that oversee the strategic development of the villages for the benefit of the neighbourhood and protect it from extinction and eviction. “Once creek restoration is done, we can imagine people fishing using traditional methods as also through aquaculture, which is a method of controlled fish cultivation. When the water is clean, waterways can also be developed for transport which offers better, easier and cheaper commute over roads and bridges. The ideas are all rooted in tradition,” Ketaki says.

While urban planners, policy makers and development agencies might not look at the cultural aspects of a place when restoring it, Ketaki says, for Kolis, the sea forms a cycle of life. “Narali Purnima celebrated by Kolis where they offer coconuts to the sea and worship the water, shows how deeply intertwined their lives are with the sea and how they respect it. This is how we can protect our sea city from turning into a sinking city, by restoring the water systems and developing Koliwadas in responsible ways.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!