A daughter’s documentary on her Olympian father becomes a larger story about history, nations, and sport and the bonds that Partition could not break

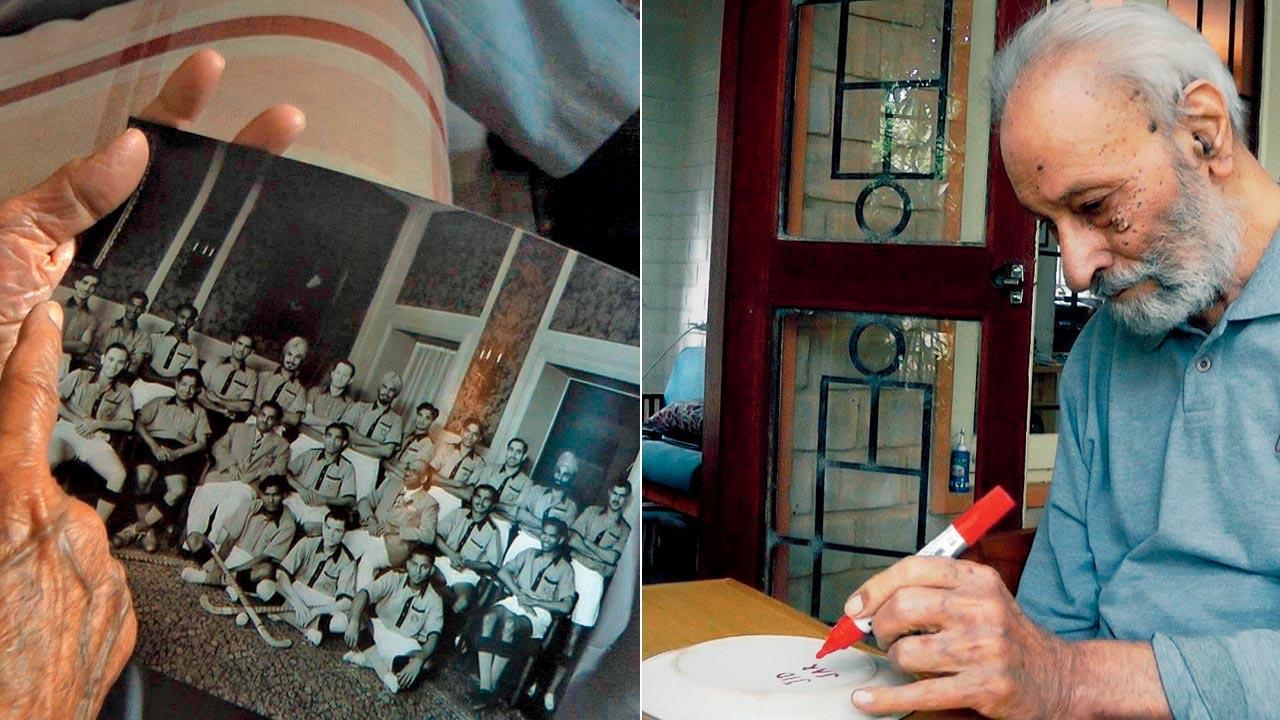

Nandy Singh was a member of the Indian hockey team that won the gold at the ’48 and ‘52 Olympics. He suffered a stroke at the age of 84 and his daughter and filmmaker Bani Singh speaks of recognising the Olympian as she watched her father face his illness with courage and grit. Pic Courtey/Film Southasia and Asia Society India

It's only a 50-minute flight from Lahore to Delhi, but an immeasurable emotional distance. It felt like I went behind enemy lines, but when I found the enemy, he was a friend!” We hear Bani Singh narrate in her 2021 documentary Taangh (Longing), as she flies back from Lahore having met Shahzada Shahrukh, vice-captain of the Pakistan Olympic hockey team of 1948. Singh’s father, Nandy Singh, was a member of the India hockey team that won gold at the ’48 and ‘52 Olympics and the film centres on journeys—both real and metaphorical—into the past that the director takes, traversing a personal history to explore a larger story of Partition, hockey, and the Olympics. “I have seen many films about the Partition where the older generation narrates horrific experiences, and I did not fully connect because it was something that happened a long time ago, and was often so awful and dramatic that you wanted distance from it. And I would feel helpless,” Singh tells us. “In this film, I wanted the daughter to be the voice of the present, engaging with the past so that there can be a conversation. Something came out of that whole interaction that left you with a feeling of joy.” She also points out that the film favoured “the feminine perspective”, and not simply because it was helmed by a woman. While many she worked with felt that the story was just about the Olympic gold, “I [would] tell them that it is also a story about a daughter and father and their relationship, and trying to search for oneself within the identity of your parents, which is a universal story.”

Singh, who studied at the National Institute of Design and worked at the Virasat-e-Khalsa museum in Anandpur Sahib (Punjab) as a gallery visualiser and content interpreter, feels that her newness to film worked in her favour. “What I got from design, which I carried with me, is that I think in layers. So even when I was pursuing the story and had the camera in hand, while things were unfolding, I was seeing that this story had layers,” she observes.

Bani Singh

Bani Singh

Being a first-timer also meant that she had nothing to lose and could experiment more freely with the form. “I was feeling my way with the camera, and the story was really leading what it wanted done…It was just like you are in the moment and you are so focused on the story that you are not aware of the camera and its technicalities and rules. I feel that’s why it speaks to the audience. If somebody told me that they want to shoot like me, I’m not sure I could explain how I did it. I am not even sure if I can do it again, to be quite honest.” When seeking help from professional technicians, the film’s element of rawness had to be sustained. “We always knew that the entire treatment of the film would have to be done to advantage the amateur approach,” Singh explains. “I wanted the audience to know that I’m behind the camera. I wanted behind-the-camera and in-front-of-the-camera to be seamlessly integrated.”

Taangh also brought home the importance of archives, both personal and national.

“There was evidence of the story in the albums of my family archive. And then those could be connected to the archives of the nation [without which], the story could not have been validated,” says Singh. [The film is] in some sense a historical document because there is nothing in it that has been recreated or tampered.” Taangh was screened at Parda Faash, a festival of films from South Asia organised by Asia Society India Centre on April 27 and 28. Head to asiasociety.org/india to learn more.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!