It seems that it is no longer daring, glamorous, exciting to be a hard-nosed journalist. With Gen Z freshers abruptly switching gears, is it boiling down to passion Vs pay?

Journalism students discuss the day’s news at St Paul’s Institute of Communication Education, Bandra West. Pic/Shadab Khan

My parents didn’t want me to study journalism; they were afraid that I’d be killed or thrown in jail if I reported on anything controversial that angered the wrong people. I stuck to my guns, and when I got through to IIJNM [Indian Institute of Journalism and New Media in Bangalore], I felt like I had been right to insist on this career choice. But then we got an email informing us that the college was shutting down,” says Arundhati (name changed), a 20-year-old Bengaluru student.

The news that the premier Bengaluru J-school was closing its doors has surprised the media industry. “It’s true, we are shutting down as we did not get the expected number of applicants for the programme,” IIJNM dean Kanchan Kaur confirms to Sunday mid-day.

Across social media and newsrooms in the country, there have been intense discussions about what it meant for the industry when one of India’s most prestigious journalism programmes had failed to reach the minimum number of applicants required to keep its doors open. We then asked—does no one want to be a journalist anymore?

Journalism students discuss the day’s news at SIES College, Sion. Pic/Atul Kamble

Journalism students discuss the day’s news at SIES College, Sion. Pic/Atul Kamble

Arundhati is asking herself the same question. “Since the news broke, there’s been all this talk on social media about how nobody wants to get into journalism anymore, that it’s a dying field. It’s added more fuel to my parents’ arguments against this profession. I’m no longer sure if journalism is the path for me either,” she says, adding, “IIJNM sent an email assuring a full refund of the admission fee, but I have a bigger problem at the moment. I don’t have any other prospects. I hadn’t bothered to apply for back-up courses. I will just have to take a step back and take stock of my options.”

It’s not just IIJNM that has witnessed this plunge in student applications for journalism courses. Just a few months ago, another Bengaluru J-school COMMITS (Convergence of Media, Multimedia and Information Technology) announced its closure after a 23-year run. Once again, the institute cited dwindling admissions. Closer home in Mumbai, Usha Pravin Gandhi College, which offers a BMM course, now has only advertising and PR as main electives. As one of these writers found out, the college instead now just offers print journalism sessions as a special class that is not graded.

“This is only the tip of the iceberg,” says Smruti Koppikar, a journalist with 35 years experience, 25 of them also as visiting faculty at Sophia Polytechnic’s post

grad social communications media programme.

Jerry Pinto. Pic/Chirodeep Chaudhuri; Swapan Dasgupta; Smruti Koppikar, visiting faculty at SCM Sophia’s

Jerry Pinto. Pic/Chirodeep Chaudhuri; Swapan Dasgupta; Smruti Koppikar, visiting faculty at SCM Sophia’s

“The news of IIJNM shutting down is huge but not entirely a surprise. It may be among a few institutes that has come out and said so in as many words, but other institutes are facing the same downward trend in numbers [of admissions]. “At SCM Sophia, we are as concerned as any other institute. But numbers are not the entire story. The way we have approached it in the last few years is to ensure that no matter the numbers, we are able to train young minds and instil the values that the media desperately needs. And we have made good on that despite all the tumult and attrition,” says Koppikar.

For those working in the industry, it’s no big mystery why more and more youth are turning away from journalism as a career choice. There are multiple factors at play, but the biggest one is also the media fraternity’s worst kept secret—abysmal pay.

The average entry-level salary for a journalist is Rs 25,000 per month, or about Rs 3 lakh per year.

Students of St Paul’s Institute of Communication Education discuss what goes into the making of a newspaper. Pic/Shadab Khan

Students of St Paul’s Institute of Communication Education discuss what goes into the making of a newspaper. Pic/Shadab Khan

This is often far from sufficient to cover the cost of a PG diploma in journalism at most colleges, where fees can go from Rs 1 lakh to Rs 9 lakh. “You finish a course that costs Rs 4 lakh, and then realise that your first package is only R3-5 lakh. Then you compare your salary to your peers who did other courses and joined other professions, and you realise journalists are paid peanuts. No one in their right mind would want to work under these conditions,” says Shubham Chohan, 23, who graduated from IIJNM’s diploma course in 2022 and is now a senior correspondent with digital news media platform, HW News.

It’s not a career for everybody, says Chohan. “The one thing this profession gives you is no two days are the same. I might hate a better paying 9-to-5 job; instead, I’m willing to work 9-to-9, so long as I get to talk to new people and work on new stories every day. There is also great satisfaction in telling the stories of people whose voices would ordinarily not have been heard,” says the young reporter.

Is it then a question of passion vs pay?

Author Jerry Pinto, who had taught the journalism module at Sophia’s for 27 years, says, “I tell my students, journalism can give you a great life, but perhaps not a great lifestyle… So which do you want? Do you want the 2BHK with a sea view in Bandra and a large car parked downstairs, or do you want to come home thinking, ‘Gosh, the farmer I spoke to has completely rewired how I look at palak [spinach]’?”

A photograph of the faculty at IIJNM, which recently shut down. The institute management said they did not get the minimum number of enrolments required to keep the doors open. Pic courtesy/IIJNM’s X handle

A photograph of the faculty at IIJNM, which recently shut down. The institute management said they did not get the minimum number of enrolments required to keep the doors open. Pic courtesy/IIJNM’s X handle

But passion doesn’t pay the rent or EMIs on loans. “In 1981, a Delhi-headquartered national media group had conducted a study, asking fresh graduates to rank what mattered to them most when choosing a profession. The number 1 factor then was the ability to make a change with the job, and at number 10 was remuneration. In 1991, they repeated the survey, but this time, the youngsters said remuneration was number 1 and the ability to make change was number 10. I can’t help but think that perhaps the latter group of students was more honest,” says Pinto.

Ananya Prasanth, 20, is honest about the importance of money for her life as well.

As an undergraduate student studying multimedia and mass communication at SIES College, Sion, Prasanth had dreams of becoming an investigative journalist. But she changed her mind in the third year of the course.

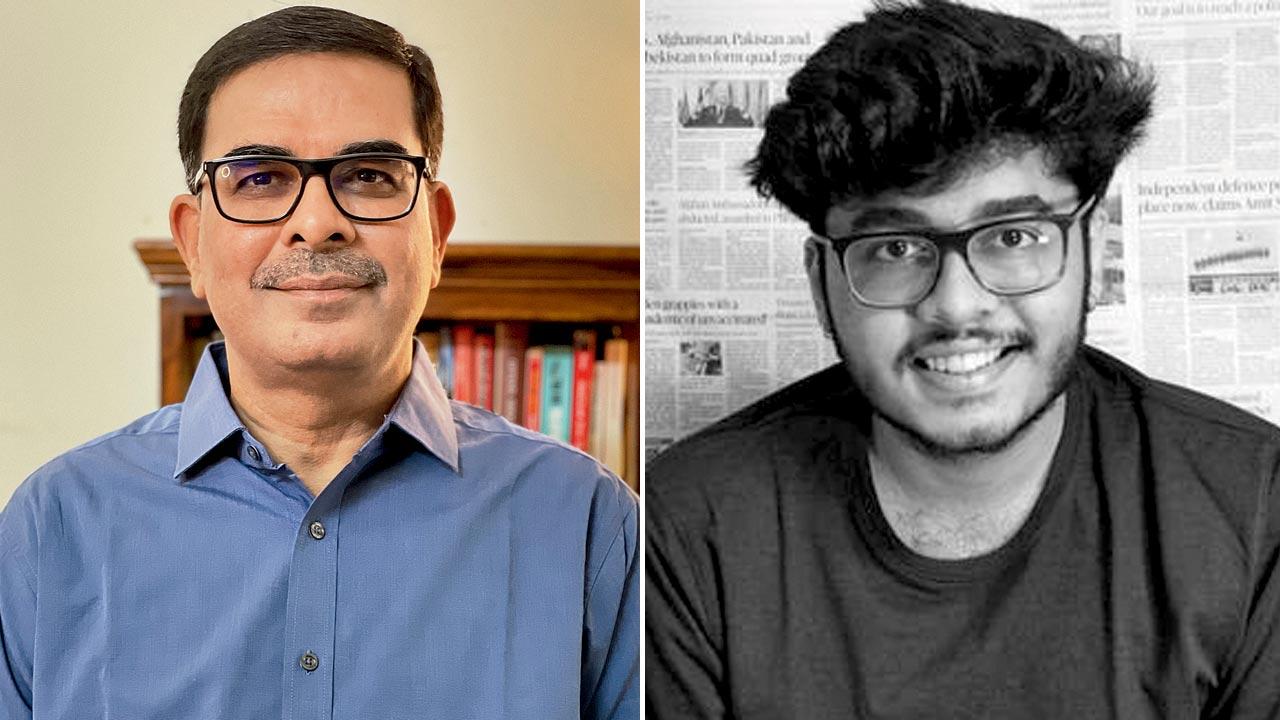

Anjali Khosla and P Sainath

Anjali Khosla and P Sainath

“A number of people suggested that I consider a different career path. They said there was a lot of competition in journalism and that the pay scale was out of proportion to the amount of work required. Financial satisfaction is very important to me,” says Prasanth, who is now pursuing a PG diploma in PR and corporate communications.

“I wanted a safe back-up option. I plan to work as a PR professional for a few years and then I might try my hand at journalism,” she says.

This is not uncommon, says Dr Vaneeta Raney, HOD of SIES’s BMM programme. “There has not been much of a decline in admissions, but most students opt for advertising or PR because those professions look more glamorous, or offer better pay,” she says.

Anand Pradhan and Shubham Chohan

Anand Pradhan and Shubham Chohan

Naziya Khan, joint coordinator of Jai Hind College’s mass media department, says that enrolments been dropping since 2020. Pre-COVID, the institute’s BMM programme would see 30-40 students per batch, but this number has been dipping since 2020, and plunged to just 11 students in the 2025 batch, she says.

“Even among the students who take up journalism as their specialisation, many end up switching career paths, and going into filmmaking, advertising, and PR,” Khan adds.

It’s not just freshers—experienced reporters and desk hands are giving up on journalism too.

Carol Andrade, Kunal Majumder and Dhruv Rathee

Carol Andrade, Kunal Majumder and Dhruv Rathee

Even a coveted MA degree from the Ivy League Columbia School of Journalism in the US didn’t shield Aayush Soni from feeling shortchanged on remuneration.

“In 2019, I quit [journalism] because I felt jaded, and the money was not enough—life is not getting cheaper. You also live the profession and there is no switch off button. So, all that gets to people,” says Soni, now a communications consultant.

“I would say that doing an expensive course like Columbia without any financial aid, doesn’t make sense. It’s better to work inside a newsroom and get journalistic experience,” he says. An MA degree at Columbia costs almost $70,000 (R58 lakh) in tuition alone.

Soni is not alone in what, in fact, seems to be a global phenomenon. In a 2022 survey conducted across 1,500 respondents in the US by job-finding service Ziprecruiter, journalism topped the list of “most regretted” college degrees, with 87 per cent journalism graduates saying they wish they had picked a different course or specialisation. The study said the respondents’ feelings about their college majors were strongly tied to their job and salary prospects after graduation.

In another study conducted in India by Lokniti and the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in 2023, more than half of the 206 journalists surveyed said they had “contemplated quitting their news media jobs altogether” and pursuing different careers.

The study pointed to a “high level of dissatisfaction among journalists regarding their profession”, as well as a general acceptance of being “more partisan”.

In the survey, 73 per cent of the journalists surveyed said they believe that media houses favour one political party.

Further, as many as 56 per cent said they were worried about losing their current new media job over their political leaning, ideology or opinions.

“In the current political climate, how many journalists will go out on a limb and ask the tough questions that need to be asked? How many organisations will back up their reporters in such cases? And when young people see this, will they be inspired to join journalism?” questions Carol Andrade, dean of St Paul’s Institute of Communication Education (SPICE).

Andrade says enrolment numbers have been dipping since the pandemic, but they are in no danger of shutting down the course. SPICE has taught as small a batch as six students during the pandemic. The priority, she says, will remain on imparting strong fundamentals in journalism to the students, no matter how many of them there are.

The blame for dwindling numbers, Andrade adds, is to be laid at the media industry’s door for creating a “hostile” work environment, with ever increasing work load while the pay remains low. “There has never been a more important time for journalism in India, but it is getting harder and harder to convince students that it is worth it when the work conditions are so hostile. If I had a child in the family, I too might tell them not to get into journalism now,” she says.

The apprehension among youth over entering journalism is also, in large part, due to press freedom violations in the country, says Kunal Majumder, the India representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, an international press freedom group. Majumder is also empanelled as visiting faculty at Jamia Millia Islamia’s Mass Communication Research Centre and has headed newsrooms at Tehelka, DNA, and Indian Express.

“In the last decade, journalism is no longer seen as a glamorous profession or one where you can do public good due to the growing number of challenges to journalists’ safety and increasing press freedom violations in this country. This has created a sense of apprehension among the younger generation about entering this field,” he says.

India is ranked 159th in the 2024 edition of the world press freedom index of 180 nations, published by Reporters Without Borders.

In 2023 alone, five journalists were killed and 226 others were targeted across India by state agencies, non-state political actors, and criminals, according to the India press freedom annual report by the India Freedom of Expression Initiative.

Some might say journalism has always been a dangerous profession with bad pay, and that it was pure idealism that drove the reporters of yore. But even with this generation, ideals are not the issue, says P Sainath, veteran journalist and adjunct faculty at the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai.

“The space to exercise idealism has been shrinking for the last 40-50 years, and dramatically so in the last 10 years. Where are the role models in mainstream media now? Everybody saw the election coverage this year. We are crushing young people’s idealism,” says Sainath.

Politicians slinging mud at journalists and using slurs for the profession in 2012-13, in the run-up to the 2014 polls, also left a mark on the national psyche, says Koppikar. “The ability of a journalist to hold authorities to accountability was devalued. When certain career journalists ceded this space, a large number of news people saw their profession be devalued too.”

According to Anjali Khosla, assistant professor of journalism + design at The New School University, New York, some of the issues that affect journalists in India are prevalent in the US as well. “There is a mass consolidation of media, and a lack of ability to find a business model for journalism since rise of social media. Craig Newmark has been forever making up for Craigslist gutting newspaper classified ad income by giving millions to journalism programmes and education,” she says.

Here in India, several established journalists have chosen to branch out and set up their own digital channels to publish news independently. “They have an impressive number of followers and it looks like this format is disrupting the industry. It shows that people appreciate credible content. However, there seems to be an unwillingness to pay for it,” says Koppikar.

And without a sustainable business model, how can one continue to spend to produce good journalism?

Meanwhile, with the growth of social media and the digital space, a chunk of advertising pie has shifted there as well. And with that, comes the rise of the ‘news influencer’,” as Koppikar puts it.

“People with no journalistic training are making reels about current affairs with 90 per cent opinion and 10 per cent facts, and are peddling these videos as ‘news’. Youngsters see these influencers rake in lakhs and think, ‘why should I sit in class to learn journalism when I can just do this’,” she says.

The problem is not just a lack of fact-checking, but also poor curation of information, says Koppikar. “On social media, all news looks equally important or unimportant.” A post about an A-lister’s celebration and another about heat stroke deaths for instance. The job is a measured, trained editor with experience is to put news in context for the reader.

YouTuber Dhruv Rathee, who is being seen as a content creator of note, especially after the 2024 elections, says that he regards himself as a secondary source of news. “The medium or format may have changed, but traditional journalists are still as needed as ever. Their job is to raise people’s issues and hold the authorities to account. I see myself as a YouTube educator, I’m only the secondary source of news. The primary source still remains the hardworking journalists on ground. I hope people are encouraged to pursue both professions seeing my work.”

IIMC’s Prof Anand Pradhan maintains that no matter the format, formal training in the principles of journalism will make a big difference. “Without proper training in fair, transparent and balance reportage, there’s a danger of blurring lines between journalism and entertainment… there is a risk of misinformation, lack of accountability, and sensationalism. While independent journalism can thrive online, formal training remains valuable for maintaining journalistic integrity and credibility,” he says.

Not everybody is sad to see J-schools lose participants, though. Swapan Dasgupta, veteran journalist, former Rajya Sabha MP and member of the BJP National Executive, believes that journalism will survive, whether or not J-schools do. “I think it has always been a niche profession—for 10-15 years, there was some glamour attached to it, but it wasn’t well paid. Now, technology has transferred, and it’s all about YouTube and such platforms. So, it’s not as if it will cease to exist; it will assume a new form. And if the youth find it challenging, then they are in the wrong profession. It does put you in precarious situations and some level of danger is inbuilt into it. As far as the political situation goes, thank god for that. The new journalist wants everything on a platter. They don’t want to go through any kind of learning curve. If you ask me, all journalism schools should shut. Learn the one language [you want to report in], and then join a newsroom. You will learn everything you need to if you have an inquisitive mind,” he says.

There are some in the industry who believe that digital media and multimedia journalism are the future. Shailaja Bajpai, dean of the newly opened ThePrint School of Journalism, says, “I don’t think it’s the death knell for journalism. In fact, I think it’s a really exciting time to be a journalist, with all the multimedia opportunities. Now you can write stories, you can do podcasts, you can have your own YouTube channel.

ThePrint School of Journalism’s 17-week online course costs R99,000. “The first batch of 28 students started the course in May. It’s not an academic approach, it’s entirely skill-based in this course,” says Bajpai.

“It’s not the end of the road, rather there are new paths opening up and we have to adapt to them,” she concludes.

24

No. of years reputed Bengaluru media institute IIJM ran journalism course before closing this month

159

India’s rank among 180 nations on the world press freedom index

87%

Journalism graduates in a US survey said they regret choosing this specialisation

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!