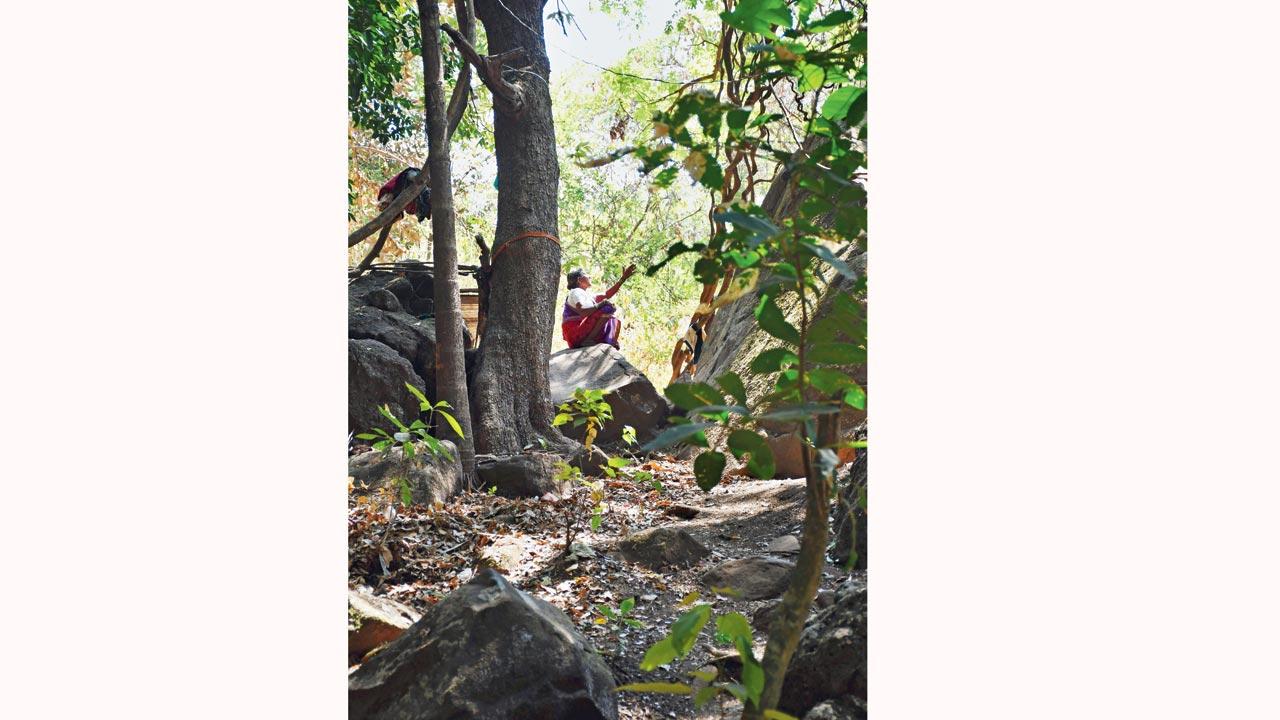

Maharashtra’s century-old sacred groves showed us what nature could look like if humans kept away. As their fate hangs in the balance and original guardians turn disillusioned, mid-day gets into the greens to find earnest effort to preserve what remains

Maharashtra’s sacred groves are ‘virgin’ tracts of forest land, making them biodiversity hotspots. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

“Are you a believer?”

Saili Palande Datar poses an arresting question as we make our way to Mulshi near Pune city. The historian and ecologist will soon guide us through two

sacred groves in the area—devrai, as they’re called in Maharashtra. These tracts of “virgin” forest land are revered and protected by local communities, who believe that they are presided over by deities like Waghjai devi. “If you were to ask, ‘What would flora and fauna look like if there was little to no human interference,?’ the answer could possibly be found in a devrai,” Palande Datar announces, “It is the site of unhindered growth of trees, plants, shrubs, herbs, orchids, fungus—all of which occupy their own niches.”

As we cross a narrow highway and wander into the first devrai, we are hit by a palpable drop in temperature. Leaves rustle under our feet, and hundreds of cicadas burst into song; it is nearly impossible to hear the cars passing by mere feet away. We may not be believers in the conventional sense, but the magic of such a sacred grove cannot be shrugged off.

In a number of devrais, vermillion-streaked rock idols are now being replaced with concretised temples

In a number of devrais, vermillion-streaked rock idols are now being replaced with concretised temples

Devrais are regarded as successful case studies of community conservation efforts. To this day, in many groves, individuals desist from using up the natural resources available. The result? Biodiversity hotspots nurtured across generations using traditional knowledge. “Complexity and close-knit connections make ecosystems more resilient and stronger. Devrais are good examples of what we should strive for, for human survival,” says Palande Datar. These groves could be marked out by ancestors for a variety of reasons: the protection of a stream, or the safeguarding of an anti-venom producing plant. Changing norms of community and faith have meant that the rules are now being changed in some groves; resources like honey and deadwood are collected, sometimes sustainably, but oftentimes not.

For centuries, local communities have perpetuated conservation practices through oral traditions. With the arrival of British naturalists, and more significantly the work of ecologist Madhav Gadgil and botanist VD Vartak, began the formal study of these hotspots. While the legendary duo studied about 233 devrais, there are varying estimations of the total number of devrais in the state, and every passing year brings worrying updates about their destruction.

It was when she undertook open-circuit treks 20 years ago that Palande Datar, currently a Research Fellow at the University of Exeter, first came across devrais, which instantly fuelled her curiosity. Pointing to an orange-and-brown Forest Calotis lounging on a tree branch, and handing us fallen figs, the Indologist tells us about her plans for a day trip to these groves in Mulshi on April 21, in collaboration with Pune’s Rupa Rahul Bajaj Centre For Environment And Art.

The jagged trunk of a tirphal tree. Those who “re-grow” man-made groves on barren land study climatic zones and the flora in them to curate a list of species to put together

The jagged trunk of a tirphal tree. Those who “re-grow” man-made groves on barren land study climatic zones and the flora in them to curate a list of species to put together

While some may be hundreds of years old, others can be surprisingly young, says Palande Datar. “Maintaining a grove across generations is not easy. It’s like a living treasure out in the open—many would like to have a piece of it,” the academic says of these “relic forests”. Piece by piece, devrais are indeed being lost to history; research by wildlife conservationist Erach Bharucha suggests that as of 2014, 40 per cent of sacred groves in Mulshi were threatened—a truth as jagged as the trunk of the tirphal tree (Indian Sichuan peppercorn). Through conversations with those who have documented devrais and those who attempt to re-grow them, mid-day pieces together a picture of present concerns and future hopes.

The more remote the area, the stronger the local community’s connection to the sacred grove,” says Sachin Punekar, “This is unlike the groves located close to highways and other development projects.” Punekar is the founder-president of Biospheres, an organisation that engaged in an in-depth investigation into devrais from 2016 to 2018, in collaboration with the State Forest Department. Through explorations in the Sahyadri and Konkan regions, he took a magnifying glass not only to the biota (living beings) in the groves but also their cultural set-ups—the beliefs and taboos associated with them, as well as the customs and rituals practised.

What emerged from Biosphere’s investigations was a change in the way local communities see their sacred groves. “In the past, there was an umbilical bond between nature and those who resided in it,” says Punekar, “That bond is lost today, owing to factors like migration to cities, weakening young people’s attachment to nature.” The way that festivals and rituals were once observed in sacred groves, too, has changed and diluted, as villagers drift away from tradition.

A Forest Calotis spotted at Mulshi’s Waghjai devrai. Matters of ownership complicate the conversation around groves’ protection; they are spread across privately owned land and protected forests

A Forest Calotis spotted at Mulshi’s Waghjai devrai. Matters of ownership complicate the conversation around groves’ protection; they are spread across privately owned land and protected forests

Where old temples were once covered in moss and ferns, now typical concrete structures have come up in their place—a consequence of not just eroding values, but also a lack of recognition in policy and law of sacred groves’ distinct identity. Within the fine print about land use in India, there’s no category where such groves fit perfectly, rues Palande Datar. “Conservation reserves, community reserves, biodiversity heritage site—these are some of the terms that can be applied to groves,” she says, as bulbuls chatter away in the distance.

Experts say that matters of ownership complicate their preservation and conservation; there is a lack of clarity about where the buck should stop. “Some groves are in protected areas—as part of sanctuaries—which makes forest departments their custodians. But many groves are located on private or nazul [government-owned] land,” says Punekar, who cites the Biological Diversity Act, 2002 which mandates the formation of biodiversity management committees to nurture and protect sacred groves that fall under their jurisdiction.

Consultations with devrai dwellers and capacity-building initiatives could go a long way in lengthening the lifespan of groves. “Government takeover of land is not the solution. The original stakeholders should adopt a joint ownership approach to undertake vital tasks like documenting flora and fauna, and establishing boundaries and maps,” says Palande Datar, “That willingness is conspicuously absent.”

The fear that was once associated with devrais and their presiding deities is now fading, changing local communities’ sense of belonging to them

The fear that was once associated with devrais and their presiding deities is now fading, changing local communities’ sense of belonging to them

Quite unlike conventional eco-tourism initiatives, the Rupa Rahul Bajaj Centre’s day trip is an example of how city dwellers can be made aware of the secrets that are unearthed when one scratches the surface. “Experiencing such a space first-hand allows people to recognise what makes devrais distinct from plantations or botanical gardens,” says the centre’s head, Dhanashree Paranjpe, “The presence of an expert lets visitors into the nuances of the sacred grove and the details they may not have noticed by themselves.”

The long, cool shadows cast by Maharashtra’s traditional devrais may be gradually waning, but some have devised ways to ensure that they do not become a relic of the past. Though environmental stakeholders have differing opinions about their value, arguing that they are “plantations”, organisations in the state have embarked on projects to “re-plant” and establish new groves in barren spaces, in a bid to increase forest cover.

“The ‘mul’ or virgin sacred grove cannot be fashioned by man, it is nature’s creation. This is why we term our projects ‘man-made devrais’,” says Raghunath Dhole, co-founder of the Devrai Foundation. After a dedicated study of groves and the species of flora that grow in them, his team began drawing up plantation plans for individuals who dreamt about setting up their own devrais; they even threw in free saplings to help start this verdant journey. “An area’s ecology is determined by the climatic zone it falls in. Our curation of species is guided by this science, and we know we’ve picked correctly when we see them flourishing,” says Dhole, who is an alumnus of the Ecological Society of India.

Saili Palande Datar, Indologist and ecologist

Saili Palande Datar, Indologist and ecologist

The Foundation has catalysed the bloom of over 300 green patches in Maharashtra and its neighbouring states. Some projects have featured a humble 41 species across 55 trees, while others assumed an ambitious scale. The one in Chambli, Purandar, is spread over 15 acres, with 6,000 trees and 80 species. “Our work in Sangamner, where we planted one lakh trees, began about 20 years ago. As of today, about 70 per cent of those trees have survived and the water table has risen by 10 feet,” Dhole says with pride. Part of the Devrai Foundation’s outreach involves tracking the progress of their projects.

The young and old in the local community who reside near the grove are educated about the flora contained within it, as well as the ways in which they can use it. “They’re encouraged to build a positive relationship with the devrai, to recognise its value as a place where events like birthdays and anniversaries can be celebrated amid nature, in an eco-friendly manner,” Dhole explains, “Because it’s a man-made devrai and not a natural heritage site, houses or temples can be built within its territory to foster familiarity and positive attachments.” If the grove acts as the backdrop for precious childhood memories, it will help young adults feel a connection to nature, says the Vice President of the Maharashtra Vruksha Sanvardhini.

Similarly, Sahyadri Devrai—set up in 2016—springs into action when groups of people or gram panchayats nominate empty tracts of land in their villages to be transformed into sacred groves. This approach builds on founder Sayaji Shinde’s early experiments in afforestation. His colleagues describe the Sakharwadi-born actor and environmental activist as a “true village and farm man”—driven to replace twice as many trees as the number that are felled.

The organisation boasts of over 29 projects across Maharashtra—in districts such as Yavatmal, Sangli, Solapur and Latur, where thousands of trees have been nourished. In its efforts to replant devrais, it has relied on expert inputs from plant taxonomists (biologist who groups organisms ito categories) like Chandrakant B Salunkhe and SR Yadav. “It’s like bringing a child into the world,” says Tushar Desai, a senior leader in the organisation, “The planting of the trees and shrubbery is only the first step. Ensuring a consistent supply of water, protecting them is the challenge.”

A thousand trees can be planted and entire forests can be plotted, but the intangible—an abiding belief in the divinity of a sacred grove—cannot simply be conjured up, even by the most devoted naturalists and policy experts. Crucial to their preservation is re-instilling a sense of belonging and faith in the local communities. “The fear that these groves once evoked is slowly fading away,” observes Palande Datar, “There is some disillusionment about matters of faith. The divinity of an idol may be recognised, but newer generations may wonder what sacredness has to do with a tree, a leaf, or a stream.”

Tragically, devrai dwellers are the first to face the brunt of their shrinking presence. “Sacred groves are the last hope for the ecology of many rural areas,” warns Punekar, “Once upon a time, they were connected to the larger forest surrounding them. Today, they appear as ‘islands’... Perhaps what is needed is a Jungle Jodo Abhiyaan—to save whatever remains of these groves.”

Inside the devrai, the supernatural is a composite identity. As Palande Datar puts it, “Te devacha raan nahiye, te raanach dev aahe [it is not God’s forest; the forest itself is godly].” Initially, the reigning deity in the devrai would not even be marked with a rock or idol painted vermillion

In search of the sacred

. Inside the devrai, the supernatural is a composite identity. As Palande Datar puts it, “Te devacha raan nahiye, te raanach dev aahe [it is not God’s forest; the forest itself is godly].” Initially, the reigning deity in the devrai would not even be marked with a rock or idol painted vermillion

. The deity is not always benevolent, it can be malevolent too; there are consequences for endangering the devrai or consecrating it. This includes being cursed and turning into a creeper!

. It isn’t just celestial beings who find a place in devrais; deities can also take the form of a revered ancestor, like a forefather who fought off a tiger, or an anthropomorphised animal or insect, like the termite queen—a symbol of everlasting fertility and continuity, embedded in the Earth

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!