It is unrealistic to think BJP’s coalition partners will strive to reverse the democratic slide witnessed over the last decade. Will the judiciary protect citizens from the executive’s wrath?

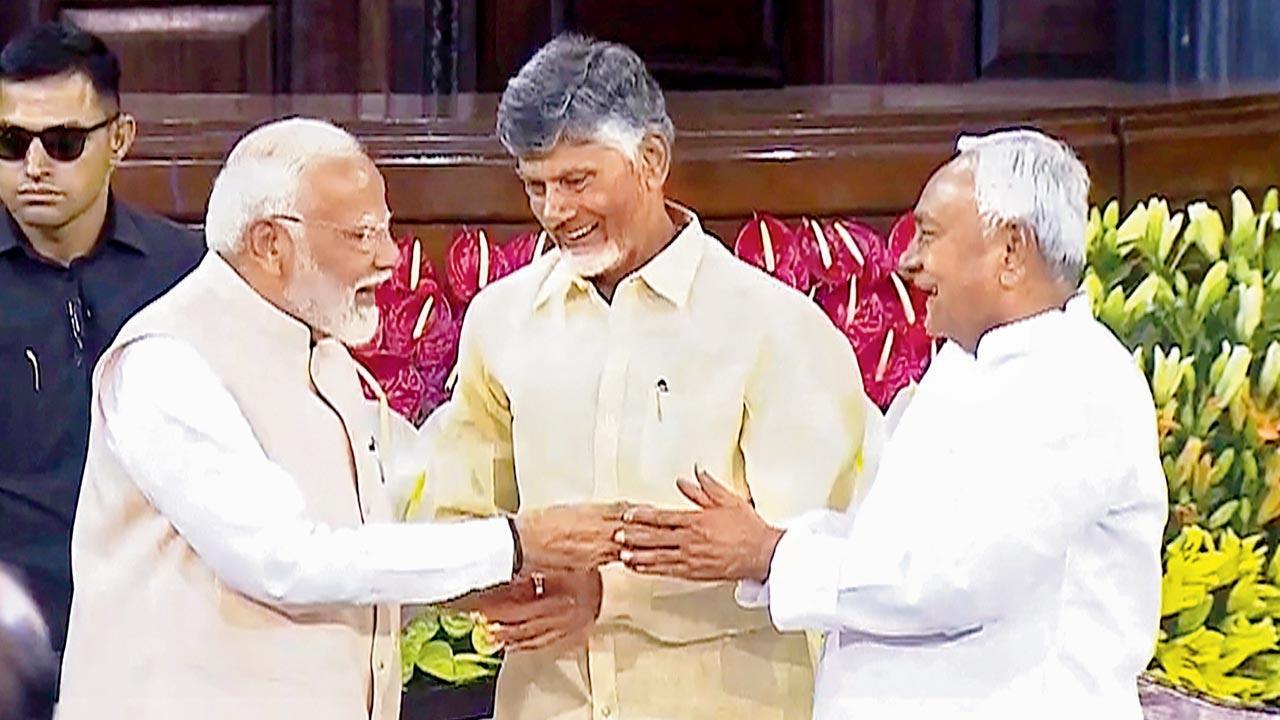

Prime Minister Narendra Modi with TDP chief N Chandrababu Naidu and Bihar Chief Minister and JD(U) leader Nitish Kumar during the NDA parliamentary party meeting at Samvidhan Sadan, in New Delhi, on June 7. Pic/PTI

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s failure to win a majority on its own in the Lok Sabha has engendered hopes that our public life will now be normalised and the democratic slide reversed. There are already encouraging signs of it: no longer do we hear of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s magical winning touch. No longer is he seen alone in media visuals; he now shares the photo-frame with N Chandrababu Naidu and Nitish Kumar, the two leaders on whom his political longevity depends. No longer is Rahul Gandhi a mere media footnote. Add to this the frisson over stories on the demands of the ruling National Democratic Alliance’s constituents.

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s failure to win a majority on its own in the Lok Sabha has engendered hopes that our public life will now be normalised and the democratic slide reversed. There are already encouraging signs of it: no longer do we hear of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s magical winning touch. No longer is he seen alone in media visuals; he now shares the photo-frame with N Chandrababu Naidu and Nitish Kumar, the two leaders on whom his political longevity depends. No longer is Rahul Gandhi a mere media footnote. Add to this the frisson over stories on the demands of the ruling National Democratic Alliance’s constituents.

All these elements alone do not assure a reversal of the democratic slide. A defining aspect of this slide has been the society’s fear of the State’s coercive powers, unabashedly exercised over the last 10 years. It muted dissent and shrank the rights of citizens. Our political life cannot rediscover its vigour unless the people’s fear of the State ebbs.

As of now, our fear has, indeed, segued into optimism.

Yet we cannot predict with certainty that raids on the BJP’s political rivals will cease and they will not be packed off to jail. Or that pressure will not be mounted on media outlets to sing the glory of Modi, and the recalcitrant among them served tax notices and booked under draconian laws. Or that protests of civil society groups will not be broken and participants hounded, with houses of their leaders bulldozed.

Hindutva is in the genetic code of the BJP, which has it favour the politics of belligerence. And so, will vigilante groups slip into oblivion? Will everyday demonisation of Muslims end? Will Dalit activists speak against Brahminical Hinduism without fearing reprisals? Will Left activists and intellectuals no more be tarred with the epithet of anti-national? The list is long, for the sources of our fears are multiple.

It is perhaps unrealistic to hope the coalition partners of the BJP—principally Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party and Kumar’s Janata Dal (United)—will emerge as the nation’s conscience-keeper. Between themselves, they command 28 MPs. These numbers are no doubt vital for Modi to survive in power. But do remember, the BJP had just 182 MPs when A B Vajpayee began his prime ministerial innings in 1999, as against Modi having the cushion of 240 MPs today. Yet Vajpayee ruled for five years, despite a Hindutva group burning alive Christian missionary Graham Staines and his sons and the 2002 pogrom in Gujarat.

Yes, Naidu and Kumar will likely veto the implementation of the National Register of Citizens, the adoption of the Uniform Civil Code, and the possible bringing to the front-burner the contentious issue of the Gyanvapi mosque. Yet we would be deluding ourselves in case we think they will withdraw their support to Modi at the first instance of an Opposition leader being raided or free speech being imperilled.

Naidu and Kumar lack the ideological firmness of the Left. Yet the Left, which with 59 MPs supported from outside the coalition government birthed in 2004, could not prevent then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh from signing the civil nuclear agreement with the United States. Nor did its withdrawal of support to the Singh government lead to its fall. Prime Ministers of even rag-tag coalitions command multiple instruments to ensure their survival.

The society’s fears would ebb if the judiciary were to stop being, to quote Lord Atkin, “more executive-minded than the executive,” as it has been over the last 10 years. History says the judiciary discovers its verve during the tenure of coalition governments. It is bewildering why this should be so. Nevertheless, a definite marker of normalcy returning would be grant of bail to eight of the 16 accused in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon case and 12 of the 18 arraigned in the 2020 Delhi riot case. They have been repeatedly denied bail even though charges against them have not yet been framed years after they were arrested.

Yet another marker would be the judiciary setting free Manish Sisodia, the former Delhi minister who was denied bail in the Delhi Liquor Policy case even though the Supreme Court observed that the ED had failed to establish a money trail to him. Will Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s arrest be quashed, for no evidence other than approvers’ statements testifying to his alleged culpability in the liquor policy case has been furnished? Will, for the sake of upholding the principle of federalism, the Supreme Court expedite hearing the challenge to the law the Modi government enacted in 2022, overturning its judgment that said Delhi’s Lt. Governor must act on the aid and advice of the elected government?

It is just the moment for the Supreme Court to reconsider the restrictive bail provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and the Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, which are invoked to incarcerate activists, politicians like Hemant Soren, and journalists. It must do so because a subliminal message of the 2024 verdict is that the people of India do not want to endure the fear the State unjustifiably whips up in them.

The writer is a senior journalist

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!