An evolving archive of lived experiences, whose debut edition focuses on Goa, offers climate solutions from cooks, poets, farmers and other experts who tell us how to eat and live

Srinivas Aditya Mopidevi and Srinivas Mangipudi, curators of the Climate Recipes project, at work

![]() For readers who seek sustainable eating choices, mull over dietary changes, scout for undervalued yet rich ingredients, and experiment with tasty, biodiverse recipes, climate cookbooks are a current favourite. These guides provide tips, alternatives and suggestions in appetising, colourful ways to engage the reader in a dialogue on climate action.

For readers who seek sustainable eating choices, mull over dietary changes, scout for undervalued yet rich ingredients, and experiment with tasty, biodiverse recipes, climate cookbooks are a current favourite. These guides provide tips, alternatives and suggestions in appetising, colourful ways to engage the reader in a dialogue on climate action.

This columnist was treated to a rather unique and petite book in this genre. It has a deliberately misleading title—Climate Recipes—and it doesn’t contain cooking directions in the conventional sense. It doesn’t have star chefs’ recommendations or any other attractive sales-driven

elements either.

Climate Recipes is akin to a conversation starter. It is an emerging archive of organic ideas; the first edition focuses on Goa, drawing on the wisdom of cooks, poets, immunologists, naturalists, researchers of indigenous culture, and farmers. The book is part of a residency collaboration supported by Pollinator.io (Delhi), the Socratus Foundation for Collective Wisdom (Bengaluru) and the Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts (Panaji). Though the 25 contributors hail from the coastal state and their ‘climate solutions’ emerge from their native experiences, the book has a pan-India appeal.

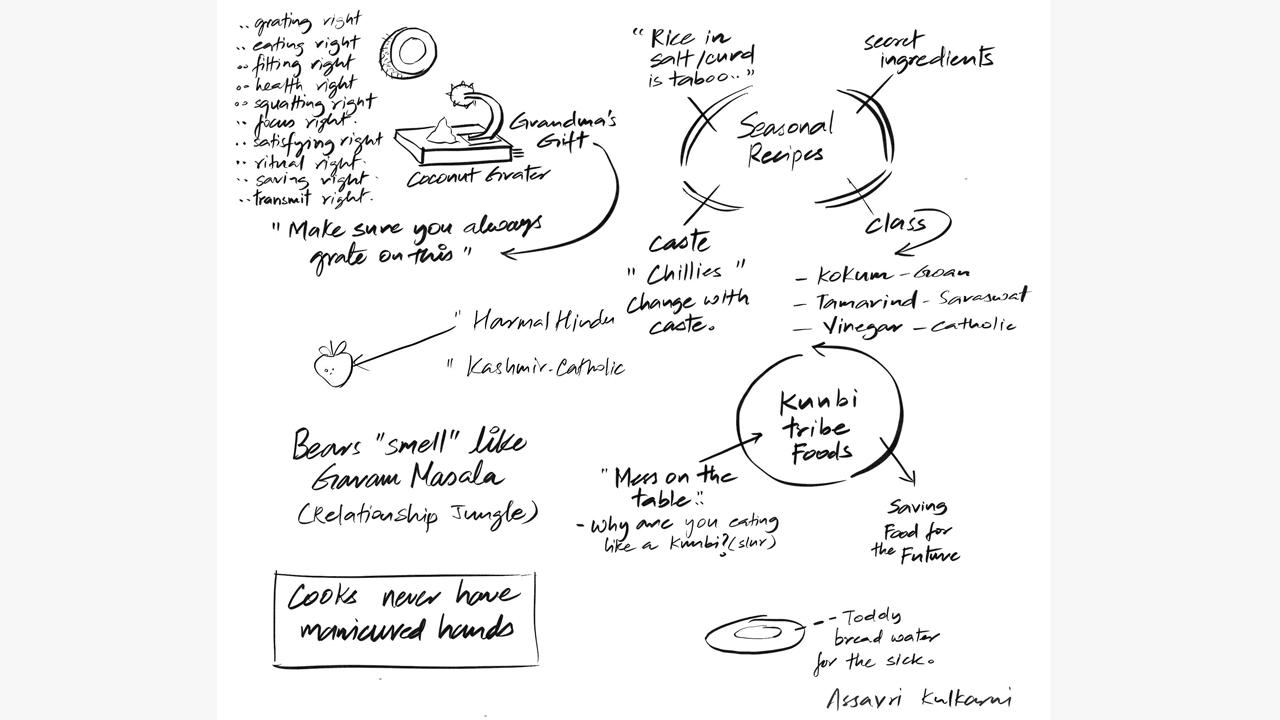

‘Make sure to use grandma’s coconut grater’: Assavri Kulkarni, artist, photographer and author of the photobbook Markets of Goa

‘Make sure to use grandma’s coconut grater’: Assavri Kulkarni, artist, photographer and author of the photobbook Markets of Goa

For instance, food historian Fatima Da Silva Gracias—respected writer of many books on the Goan cuisine—dwells on the susegad afternoon tea. Her remarks on the impact of migration on inherited culinary habits ring true for most parts of India where certain eating rituals, such as the elaborate paan gilori, have died out due to the loss of clientele.

Similarly, Vikram Doctor’s take on imported toor dal is not Goa-specific. This problem may remind many of those dreadful periods when the pulse goes off the grocery rack! He is pointing towards the rising demand for traditional foods in populous cities. Restaurants in Mumbai often use yellow peas instead of costly toor dal. Doctor drives home a universal reality—‘exotic demand’ for food (local or otherwise) is unsustainable, and that we, as inhabitants of the Earth, need to find the right balance between traditional and globalised practices of food consumption and production.

Let me offer an example of food exotica, which addresses my occasional guilt of being a voracious fish eater: Fish is admittedly a great source of omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, phosphorus and vitamins. Fish eaters go to great lengths for the best catch; fine dining restaurants fleece sea food fans all over India. However, it is a truth that large-scale fishing operations (trawlers, nets, deep-diving vessels) endanger marine life in oceans as well as smaller water bodies. A pertinent and oft-asked question is: should this form of exploitation have a bearing on the large amounts of fish we savour? Or is it wrong to raise environmental or moral issues before fish and meat eaters? The same is true of millet eaters who purchase the ‘super food’ from multinational companies, which doesn’t necessarily benefit the millet farmer.

’My house in my village will not be taller than the coconut tree’—the motto shared by Damodar Mauzo, novelist, critic, and scriptwriter

’My house in my village will not be taller than the coconut tree’—the motto shared by Damodar Mauzo, novelist, critic, and scriptwriter

Climate Recipes awakens readers to the entire gamut of unanswered questions around climate, ecology, conservation and ethics. These recipes are “entry points for an adaptable life”, as well as efforts to “create sites of refuge” in the wake of climate adversity. From forest truths, to a grandma’s advice, to internet gyaan, conspiracy theories, industry scams, marketing gimmicks and freak facts—the editors (curators, designers and visual thinkers) of the book, Srinivas Aditya Mopidevi and Srinivas Mangipudi, have included diverse voices and themes.

The duo’s “research expedition” began in Goa in May 2023. They spoke to an eclectic mix of state residents for two months—foragers, academics, chefs, planners, and architects—about their lived experiences, who in turn shared their recipes of life. Every one-on-one conversation was captured in the form of “visual notes” by Mangipudi and Mopidevi, which included scribbles, doodles, pointers, graphs and a visual mapping of the expert’s core message, work and future path.

They asked the experts to share a recipe for climate change in the context of biodiversity loss and planetary boundaries pushed by humans. “We would allow offshoots of other conversations, and then circle back to the recipe. Post the conversation, Aditya (Mopidevi) and I would synthesise the messages and key phrases to figure out an interesting entry point to the wisdom of each person’s life and work,” says Mangipudi, an artist-researcher based in Goa. Born into a Telugu family in Nagpur, he grew up in different pockets of the world.

Working as a visual thinker for several climate initiatives, Mangipudi’s interdisciplinary art practice rests on a fusion of drawing, painting, video, sound, urban intervention and generative algorithms. After the Goa edition, he aims to tap into the recipe magic in Bengaluru; Mumbai, too, is on the horizon. The duo is also in the process of setting up an online interface which will have recipes from all contributors, alongside a visitor recipe feed comprising submissions from readers.

Leandre D’Souza, program director of the Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts, one of the stakeholders behind the book, has placed it at the centre of this.generation, an ongoing exhibition at the Panaji space that focuses on code-based generative practices, which include languages, music and the culinary arts.

this.generation is an effort to make algorithms and code accessible to all, especially those excluded by technology. “We see the recipes as codes, a set of instructions that have a different outcome in different contexts. For example, training the tongue has a different meaning to someone who has only lived in cities, as against someone who grew up in the forest. The beauty of these recipes is the diversity they can generate in terms of responses and yet address the climate urgency in the current context,” says Mopidevi, who was born in Andhra Pradesh’s Machilipatnam, raised in Hyderabad and Delhi, and is currently the Principal Investigator at the interdisciplinary lab Pollinator.io. Previously chief curator at New Delhi’s Nature Morte, he is a visiting professor of Visual Arts at Ashoka University.

Climate Recipes is an expansive documentation of conversations which people are free to interpret in their own ways. At the root of the project is the enlarged definition of what a ‘recipe’ can be. A recipe holds a spell, a charm—the mystique of wisdom transmitted across generations. When a recipe is lost, the loss is not just of an individual family, but that of a neighbourhood, a society. There is also an invisible generational loss of knowledge systems (often, a mother tongue). This project is an attempt to condense the wisdom into diagrammatic, jargon-free guideposts which are accessible to the lay person who doesn’t mouth terms like geologic sequestration and ozone precursors.

The 132-page book (R265, sold only at Sunaparanta for now) resembles a collection of mind-maps or notes on a classroom blackboard which can be read in any sequential order—clockwise or anti-clockwise, either in terms of phrases that stand out or as a series of line drawings. In fact, the editors have hinged their drawings on key phrases that spoke to them intuitively. As one leafs through the drawings, the phrases stand out—‘Make Green Warrior Cool’; ‘My heart is BIG, so I will buy a Bigger Car’; ‘No bed for fish to sleep’; ‘Covid brought awareness alive’; ‘Fad eating is dangerous’.

Aside from these capsule-like self-explanatory constructs, the mind maps lead us in several directions. Permaculture practitioners Musharraf Hebballi and Praveen Yarramilli ask us to treat the body as an extension of nature. For them, “listening to the land” is to absorb the forces of the environment. Poet-writer Mamata Verlekar speaks of the loss of food-fun memories in the Konkani language. She says languages “carry philosophies and metaphors of nature in stories and poems.” Litterateur Damodar Mauzo is also deeply invested in local languages which are a medium for local recipes. He misses those fruits which are no longer seen in Goa—zagam (plum), adaon (Adam’s fruit) or seasonal mangoes, all destroyed by foreign seeds.

Divya Sehgal, professor at the Goa Institute of Management, adds a to-do task to her sustainability lecture. For her, sustainability begins with mending habits and changing individual practices. She asks her students to sew a button and repurpose old clothes to bring down their carbon footprint. Enterpreneur Paresh Shetgaonkar spells out a recipe for collective wellbeing; he has built a network of coconut farmers who nurture trees which produce high-quality organic oil. To him, Goa’s true wealth lies in its coconuts.

Mauzo, too, underscores the average Goan’s love for the coconut tree. He proudly shares the ancient unsaid understanding among village folk, about not building houses that are higher than the tallest coconut tree. This practice signified the ceiling an individual put on their aspirations and status. Mauzo’s recipe for a favourable social climate is worth a shot—in Goa and elsewhere.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!