There is steaminess, but it is disembodied, disconnected.

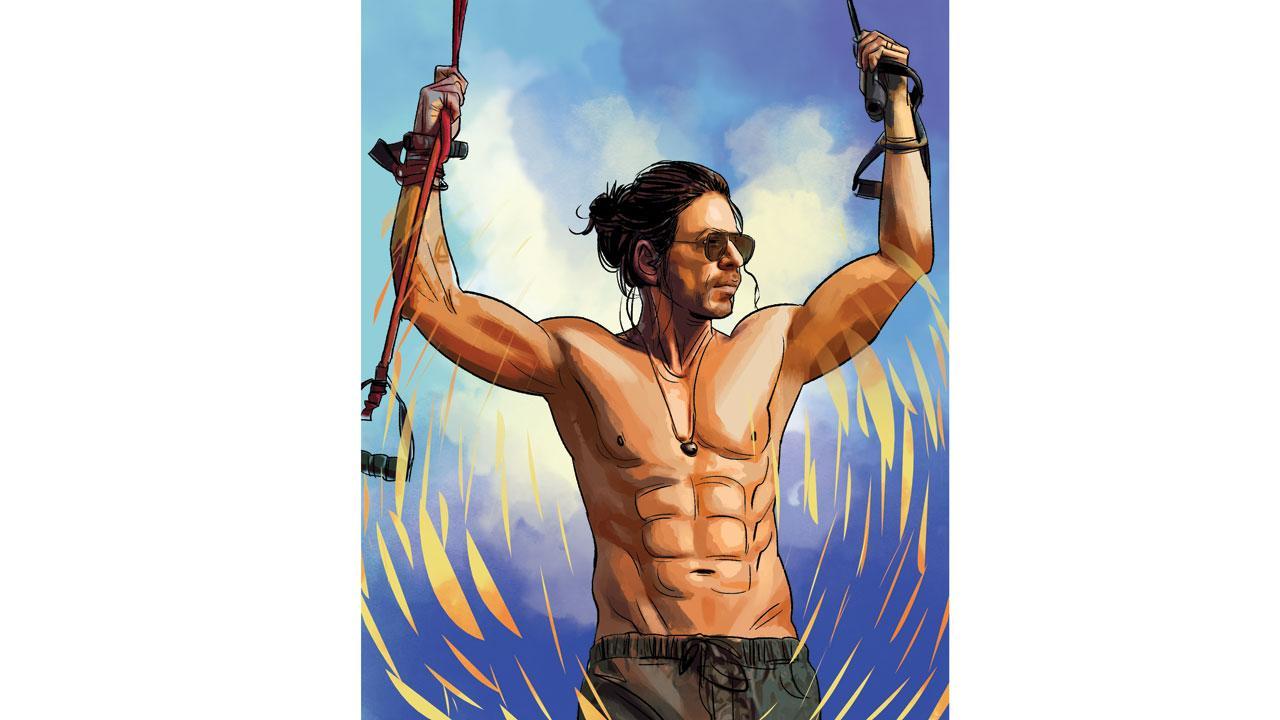

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() This is not a column about the colour of Deepika’s bikini. Noting that the baal-ki-khaal politics of saffron paranoias are stupid does not prove we are clever or even progressive, merely subservient to the left-right-left rituals of rattebaaz politics. The word on the rang surely belongs to journalist Namrata Zakaria, who tweeted, “It’s called Hermes orange guys!” What you see in the nazara is all a matter of your nazar.

This is not a column about the colour of Deepika’s bikini. Noting that the baal-ki-khaal politics of saffron paranoias are stupid does not prove we are clever or even progressive, merely subservient to the left-right-left rituals of rattebaaz politics. The word on the rang surely belongs to journalist Namrata Zakaria, who tweeted, “It’s called Hermes orange guys!” What you see in the nazara is all a matter of your nazar.

I followed the trail of online sighs to the nazaras on offer in Besharam Rang, the first song from Pathan, Shah Rukh Khan’s first movie in years. Who can deny Shah Rukh Khan’s hotness, his signature aadaab slowed to seduction speed, the hard planes of his bared body and weather-beaten eyes telegraphing a cynical sexual-ness? Different shades of cynicism have flashed through his earlier characters—Harry, Zero, even the Rajs and Rahuls all cycled through frivolity, ambivalence and non-committal emotions, before arriving at a tryst with sincerity (which we sometimes call love), but we have never seen him quite like this.

It is one thing to portray cynicism in a character. But Besharam Rang is disconcerting in how cynical it feels as an item. Its generic tunelessness and mechanical picturisation create a desiccation, leaving us with husks to feed on. Deepika Padukone is a luminously beautiful woman whose complete inability to dance has always been offset by the inherent grace in her presence. But this choreography, treating her body generically, reduces her to clumsy basics, a painfully embarrassing sight. Besharam so literally labelled is just boredom. There is steaminess, but it is disembodied, disconnected.

I’m no nostalgist. But take even an extraordinarily ordinary picturisation, like Say Shava Shava in K3G. It is generic, but it is also alive with interaction between numerous characters, a constant interplay of longing, attraction, exuberance and connection. The song allows us to enter through fun and pleasure into this experience of relationality and experience connection. We are part of something, not slack jawed voyeurs.

Amitabh Bachchan’s remarkable speech at the Kolkata International Film Festival opening ceremony traced a history of Indian cinema infused with anti-colonial and anti-fascist resistance unquelled by colonial censorship, encouraging us to see parallels with contemporary fascism and censorship. But Hindi cinema was decolonial not only because of the swaraj-coded lyrics of songs like Door Hato Ae Duniya Walon, Hindustan Hamara Hai. It was also decolonial for being saturated with emotion, pleasures of performance, queer eroticisms and exaggerated witticisms, cultural expressions that had been invalidated and outlawed as vulgar and inferior by the British through things like the anti-nautch campaigns. That world was embodied in the songs, which celebrated the mind’s eye through fantasy, dream, glamour and role play. Their besharam rang, rangilapan and bhav asserted a self-acceptance that countered the rejecting colonial gaze, the censorious nazar which seeks to feel shame about who we are. This amorphous, sensory frame of pleasure brought people together not as one— which after all fascism too seeks to do— but together as many, a hetrogenous inclusivity. Besharam Rang’s emptiness is the opposite of this.

SRK always commits to being the life of the party and here too tries. As he valiantly, singly, attempts to bring some life to the inert proceedings, he seems a little lonely. Or maybe we are, for those five minues.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at paromita.vohra@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!