A new Marathi translation looks back at the amicable dialogue between the Mahatma and his atheist disciple Goparaju Ramachandra Rao in Sevagram, offering lessons for an increasingly intolerant society

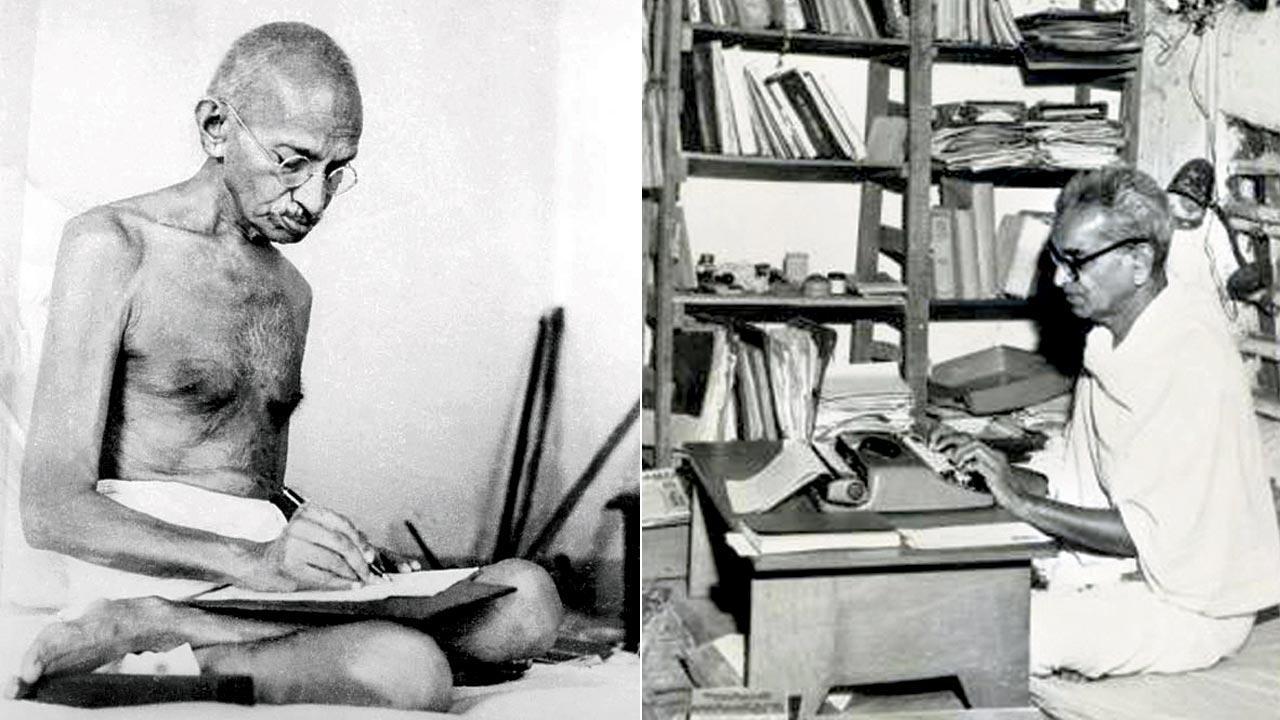

Mahatma Gandhi and Goparaju Ramachandra Rao met at the Sevagram ashram in Wardha in 1944, where they had a free-flowing and respectful conversation about atheism

![]() God is beyond human comprehension.” This was the short, rather cryptic reply given by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930 to Goparaju Ramachandra Rao (Gora), an anti-untouchability, anti-caste reformist who was active during the Quit India Movement. Gora, a declared atheist, was not satisfied with the reply. He wanted the Mahatma to elaborate on the meaning of God and how far is it “consistent with the practice of life”. But there was no time for further correspondence, as he himself got busy with the Salt Satyagraha, and was teaching botany for a living.

God is beyond human comprehension.” This was the short, rather cryptic reply given by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930 to Goparaju Ramachandra Rao (Gora), an anti-untouchability, anti-caste reformist who was active during the Quit India Movement. Gora, a declared atheist, was not satisfied with the reply. He wanted the Mahatma to elaborate on the meaning of God and how far is it “consistent with the practice of life”. But there was no time for further correspondence, as he himself got busy with the Salt Satyagraha, and was teaching botany for a living.

ADVERTISEMENT

In September 1941, Gora again wrote to Gandhiji seeking an appointment for a discussion on the effectiveness of eradicating caste in an atheist setting. Gandhiji wrote back saying, “atheism is a denial of self”, but said he had “no time to spare for talks”. The dogged Gora’s wait for Gandhiji’s audience ended in November 1944 when he was called at Wardha’s Sevagram ashram for a chat. The conversations—free-flowing, candid, respectful, undocumented and unintended for publicity—formed the core of the slim celebrated book, An Atheist with Gandhi.

Gora’s book was published in 1950, two years after Gandhi was assassinated; its Marathi translation, Nastikasobat Gandhi (Manovikas Prakashan) by Vijay Tambe, has been released 73 years later, and is a welcome addition to the literature on Gandhi in Maharashtra.

Gora who was born in an orthodox, Brahmin Telegu joint family, founded the Atheist Centre along with his wife Saraswathi in 1940

Gora who was born in an orthodox, Brahmin Telegu joint family, founded the Atheist Centre along with his wife Saraswathi in 1940

Present-day Maharashtra simmers with unresolved issues around caste, faith, class, education, access, reservations, and constitutional rights. Against such a burning backdrop, a book premised on a low-decibel dialogue on humanity and organised religion is rewarding. Gandhiji’s readiness to listen to a truth outside his realm of awareness is healthy.

Kishorelal Mashruwala, the editor of the Harijan magazine, writes in the foreword to the original book that Gandhiji held Gora in high esteem despite his views on God. “Reports of Gora’s selfless service and an undying faith in humanity had reached Gandhiji even before the duo met; Gandhiji was endeared by the loving heart of a social worker; he saw an ‘essential religiousness’ in Gora,” says Marathi translator Vijay Tambe, who was personally touched by Gandhiji’s definition of religiousness, a characteristic required in today’s intolerant times marked by religious-caste identities and widespread hatred.

Tambe, a retired banker, is credited with three anthologies of short stories. He is part of the Sevagram Collective group that promotes Gandhian values.

The Mahatma and Gora

The Mahatma and Gora

An Atheist with Gandhi underlines a tall and receptive leader’s readiness to listen to multihued followers who agreed with him on social programmes, but differed over his interpretation of faith. Gandhi had many followers and fans, and too many pressing national issues to deal with. But he didn’t dismiss Gora’s logic and claim of success in social reform. He acknowledged Gora’s appeal to reason as against an appeal in the name of a God. However, Gandhi told Gora, in the politest of words, that he credited Gora’s success not to his nastikvaad, but to the spirit of self-sacrifice, sincerity/clarity of purpose, and high principles of personal morality. They spoke in English because Gora didn’t speak Hindi.

The book is a testimony to a coming together of two beautiful minds who wished for a truly free, vibrant, cosmopolitan, inclusive and tolerant India. While one believed that religious faith did not obstruct, but rather strengthened society, the other believed that faith in a particular God complicated matters, and created segments in social settings. But at heart, both believed in the power and possibility of reform. For both, action and change began at home.

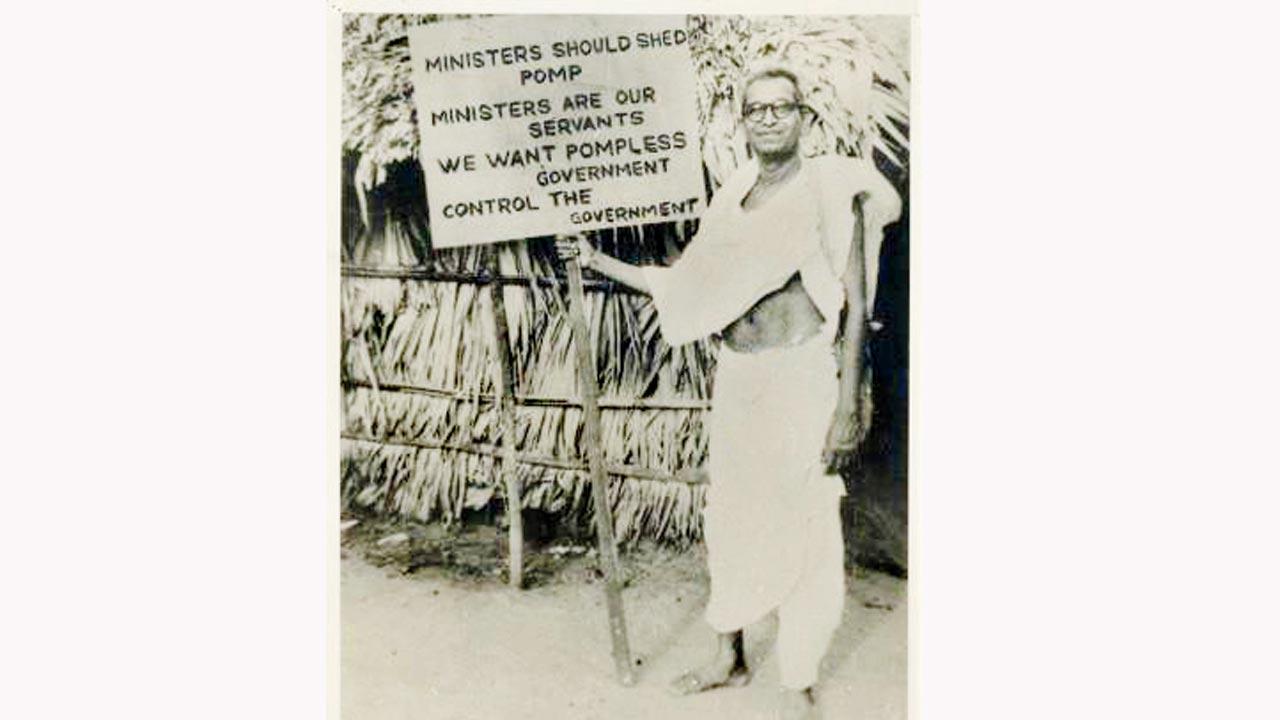

Born in an orthodox, Brahmin Telegu joint family, Gora was 22 when he married Saraswathi who was a child bride of 10 at the time. He pursued botany up to post graduation, then taught at various institutes in Madurai, Coimbatore, Colombo, and Kakinada. But activism pushed him outside academia. He and his spouse publicly viewed solar eclipses, to bust the myth about its adverse spell on pregnant women. They resided in “haunted” houses to dispel unscientific notions. In his bid to eradicate untouchability, he organised “cosmopolitan dinners for people of all castes and religions”. People paid a nominal fee of one anna for a no-frills meal. Gora was ostracised by the extended family for his views, but his wife and children formed a solid support in his endeavours. In 1942, Gora, his wife and their 18-month son were imprisoned during the Quit India Movement. Two of his four children later married members from the “lower” castes. The Gora couple founded the Atheist Centre in 1940, in a small village called Mudunur, and later relocated to Vijaywada. The centre continued under the guidance of Saraswathi Gora up to her death in 2006.

An Atheist with Gandhi is marked with distinct clarity. Gora is crystal clear about Positive Atheism rooted in social reform, which he elaborated on in his books. He was not intimidated by Gandhiji’s stature. Gora made it very clear that nastikvaad is not just godlessness or denial of an almighty power, but an affirmation of life. It is a positive construct which resides in a negative form, like non-violence. Gora says theism, in fact, presumes a human being’s subordinate status, linked to either karma or fate. Atheism pulls away all barriers, caste and religion in particular, in any social change movement. Gora said theism breeds divisions and hierarchies in the name of morality, but atheism collapses the man-made structure. Gandhiji listened to the entire argument in a series of interviews which usually took place around dawn. Neither party emerged victorious over the other; and both sides acknowledged the legitimacy of the other view.

Atheism is an unpopular subject in the Indian setting; it has a limited subscription in a country of many Gods and religions.

Voicing an atheist or a rationalist view—even quoting an ancient atheist philosopher like Charvak—can result in social isolation even in contemporary India, let aside in Gandhiji’s time. Against such a backdrop, An Atheist with Gandhi, its Marathi version, awakens us to the fearless dissident public intellectuals of Indian society, who don’t prefer silence, irrespective of the audience!

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!