An artist, who has grown up in Vidarbha where the bull is venerated, celebrates Lord Shiva’s vahana as a source of inspiration and energy

Ashok Shriram Rathod, 35, who is a life-long admirer of Nandi, has around 250-odd paintings inspired by the sacred vahana of Lord Shiva

![]() Around the time when photos of Lord Shiva’s sacred vehicle, Nandishwara, were being feverishly exchanged online to argue in favour of the archaeological remains of a temple in Varanasi, I interacted with a visual artist specialising in Nandi images. Curiously, his four new works—acrylic on canvas—will be part of an upcoming group show in Varanasi. Ashok Shriram Rathod, 35, a graduate from Sir JJ School of Applied Art, who is based in Navi Mumbai, is also currently working on three-dimensional Nandi installations. He is experimenting with clay as of now in his workshop studio, but soon will transition to fibre glass to make a life-size Nandi. “Nandi denotes anand in its purest form. To etch a Nandi on canvas or using any other medium, is a joy like none other,” says Rathod.

Around the time when photos of Lord Shiva’s sacred vehicle, Nandishwara, were being feverishly exchanged online to argue in favour of the archaeological remains of a temple in Varanasi, I interacted with a visual artist specialising in Nandi images. Curiously, his four new works—acrylic on canvas—will be part of an upcoming group show in Varanasi. Ashok Shriram Rathod, 35, a graduate from Sir JJ School of Applied Art, who is based in Navi Mumbai, is also currently working on three-dimensional Nandi installations. He is experimenting with clay as of now in his workshop studio, but soon will transition to fibre glass to make a life-size Nandi. “Nandi denotes anand in its purest form. To etch a Nandi on canvas or using any other medium, is a joy like none other,” says Rathod.

ADVERTISEMENT

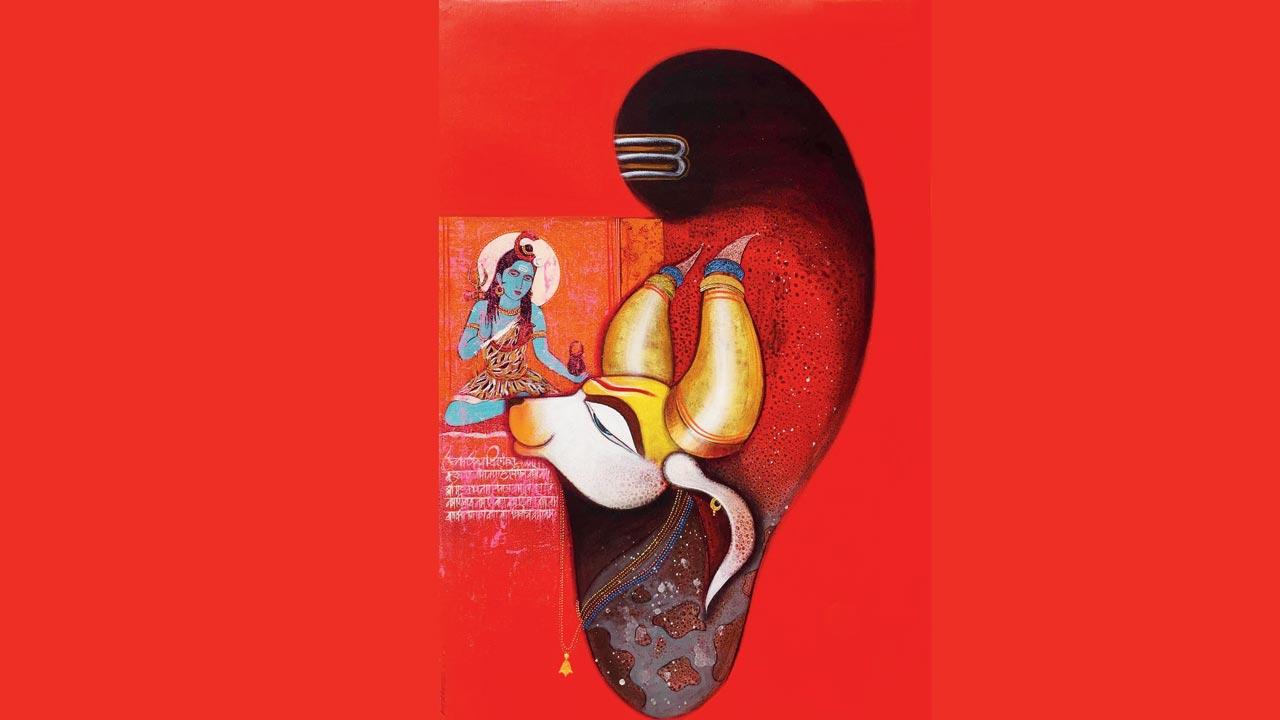

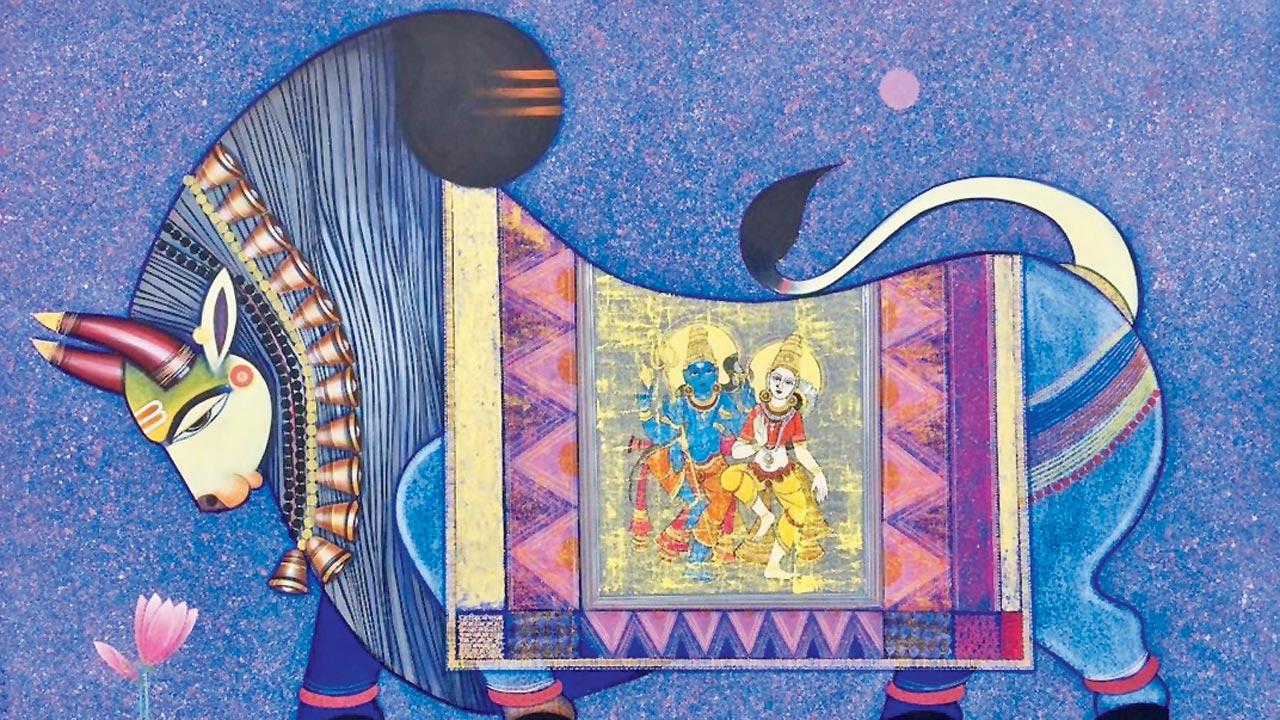

Rathod’s Varanasi show includes his signature combos—three images depicting Lord Shiva imbibed on Nandishwara’s ornate saddle cloth, denoting the oneness between the Lord and his sacred carrier. Another frame juxtaposes the divine Kamadhenu with Lord Krishna. The animal forms have been the mainstay of Rathod’s art.

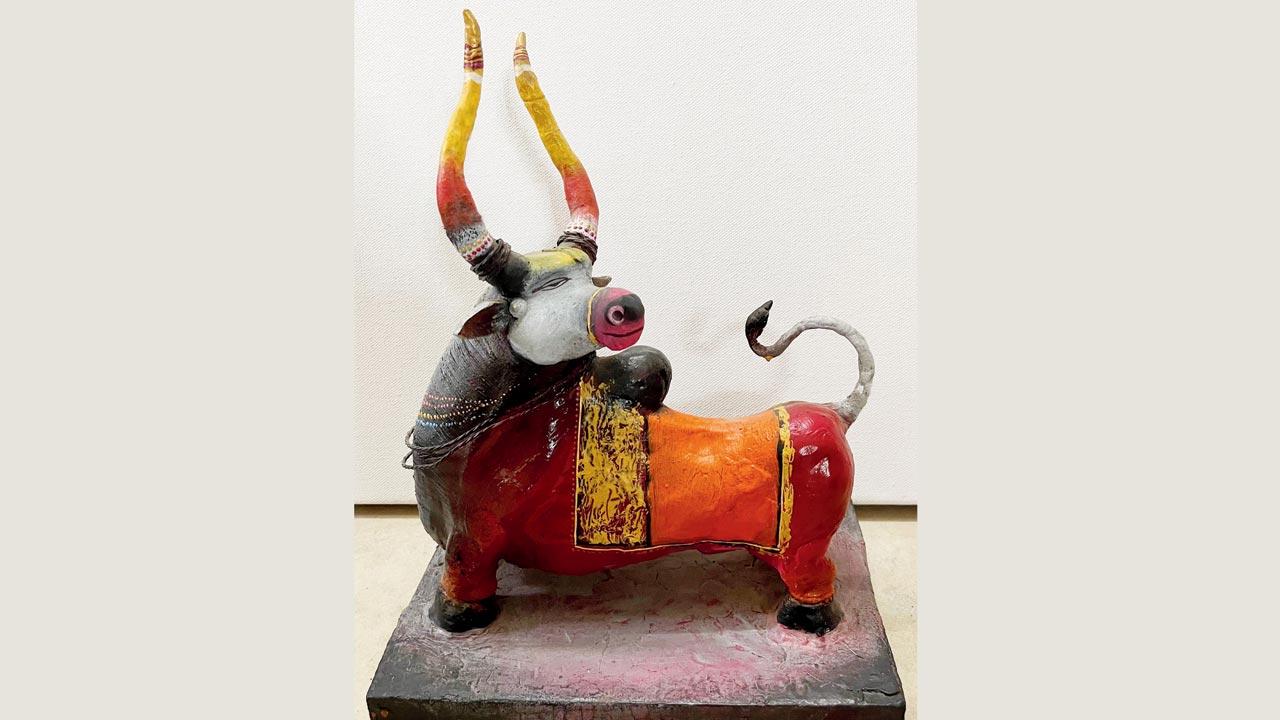

A three-dimensional Nandi installation made with clay

A three-dimensional Nandi installation made with clay

Even before Rathod became a painter, Nandi inhabited his consciousness from pre-school years.

Born in Andhera and raised in Dusarbeed, both remote villages in the Buldhana district of Vidarbha region, Rathod was raised in a Banjara family which belongs to India’s itinerant nomadic tribes. As his father worked in a sugar cooperative factory, the family lived in a housing colony provided by the management. Rathod and his sibling studied in the Jeevanvikas School in the Dusarbeed neighbourhood. The school was situated opposite a Hemadpanthi-styled Shiva temple which had a huge five-feet-tall resplendent Nandi at the entrance. This idol fascinated little Ashok immensely. He spent his lunch breaks in the temple vicinity, just so as to marvel at the Nandi. Observing the carvings on the Nandi’s body became his daily pastime; he also looked forward to festivals like Shivratri and Bailpola, which warranted additional temple visits.

Rathod’s paintings depict the oneness between Lord Shiva and Nandi

Rathod’s paintings depict the oneness between Lord Shiva and Nandi

Although Rathod had chosen the Science stream till higher secondary, he began feeling closer to the fine arts, especially painting. The grandeur of the Nandi image, a potent symbol at the Lord’s door, was among the foremost images which recurred in Rathod’s mind during his sleep and waking hours. In one such defining childhood moment, Rathod decided to study visual arts in one of the premier institutes of Mumbai. He wanted to learn the craft that would later help him capture his subject on canvas. His family was supportive of the relocation, especially after Rathod cleared the entrance exam.

The aspiring artist’s journey from Dusarbeed to Mumbai had several roadblocks. Like any new Mumbaikar, he had to seek shelter as soon as he enrolled at JJ School. He stayed at the MLA hostel in Nariman Point to begin with, latching on to a legislator’s government accommodation. But an expensive city demanded more out of him in terms of sustenance. He discontinued the course for two years and took to doing odd assignments—commercial set design, caricatures, portrait/tattoo drawings in social dos, corporate sector artwork. “I knew these adjustments were inevitable. Mumbai roughs you out before rewarding your talent,” says Rathod, who now lives in a rented studio space, and has so far survived on the “sharing basis” mantra of Mumbai. “One doesn’t mind the inconveniences of urban living, as long as one is taking baby steps towards the great dream.” At this point, he has around 250-odd Nandis to his credit, shared-archived on his social media properties and available for sale.

His upcoming works in Varanasi dwell on the same theme

His upcoming works in Varanasi dwell on the same theme

At a recent exhibition in Mumbai’s Nehru Centre, where he displayed two striking Nandishwaras, he was asked about his super-focused niche subject choice. “I can’t explain it in words. Nandi or Kamadhenu is a source of energy for me. It is elevating, mentally too. I feel it is therapeutic to bring a huge bull to life.” The artist reiterates his feelings for Nandi God in most shows, be it Dubai, Hyderabad or the Netherlands.

Rathod’s mobility and art practice were affected in the last two years due to the pandemic, though he compensated by his participation in online events organised by diverse groups situated in cities as different as Sydney, Oslo and Jaipur. “While COVID-19 was restrictive, I was happily locked in my flat with various Nandi avatars. It was a time for an inward focus, which is otherwise not available in Mumbai.”

Rathod’s fond feelings for the Nandi reflects in his choice of multi-hued vibrant colours for depiction of the bull’s majestic structure. The zhool (ornamental decorative bejewelled saddle cloth) has captivated him since childhood, as that piece of drapery sets the bull apart and lends it an otherworldliness. In fact, the zhool has emerged as Rathod’s experimentative space. The artist is heavily influenced by the miniature art on the walls of Ajanta and Ellora caves, which reflects in the intensive highly-detailed motifs Rathod etches in the zhool, some of which require a real close look. As the famed rock-cut caves are merely at a three hours’ distance from Rathod’s Dusarbeed home, he spent hours observing the art on the walls. “I have a personal connect with the art in some caves. It guides me in my everyday choices.”

Rathod’s aesthetic allows a riot of colours—a liberal use of pink, red, blue, yellow and green. Those who have had a taste of life in Vidarbha know how much of a big deal the Bailpola festivity is. It is declared a bank and press holiday when families worship the bull and oxen population for their services. Even after leaving what Rathod calls the “Bailpola land”, he continues to draws his energy from the vivid recollection of Bailpola celebrations. He recalls temple devotees in Dusarbeed who dutifully decorated the Nandi.

For most families in Vidarbha, even those like Rathod’s which had a small patch for cultivating jowar, toor and moog for personal consumption, Bailpola was a time to honour the bulls on the family farm. It was a time to thank the bull/oxen for their backbreaking ploughing work. Today, when Rathod looks back at the mythological significance of bull worship, he has many reasons to feel indebted towards the bull. He owes his career to the Nandi.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!