As Bangladesh seeks stability after political shake-up, textile advocates from either side of the Ganga emphasise the crucial role of peace in sustaining handloom traditions

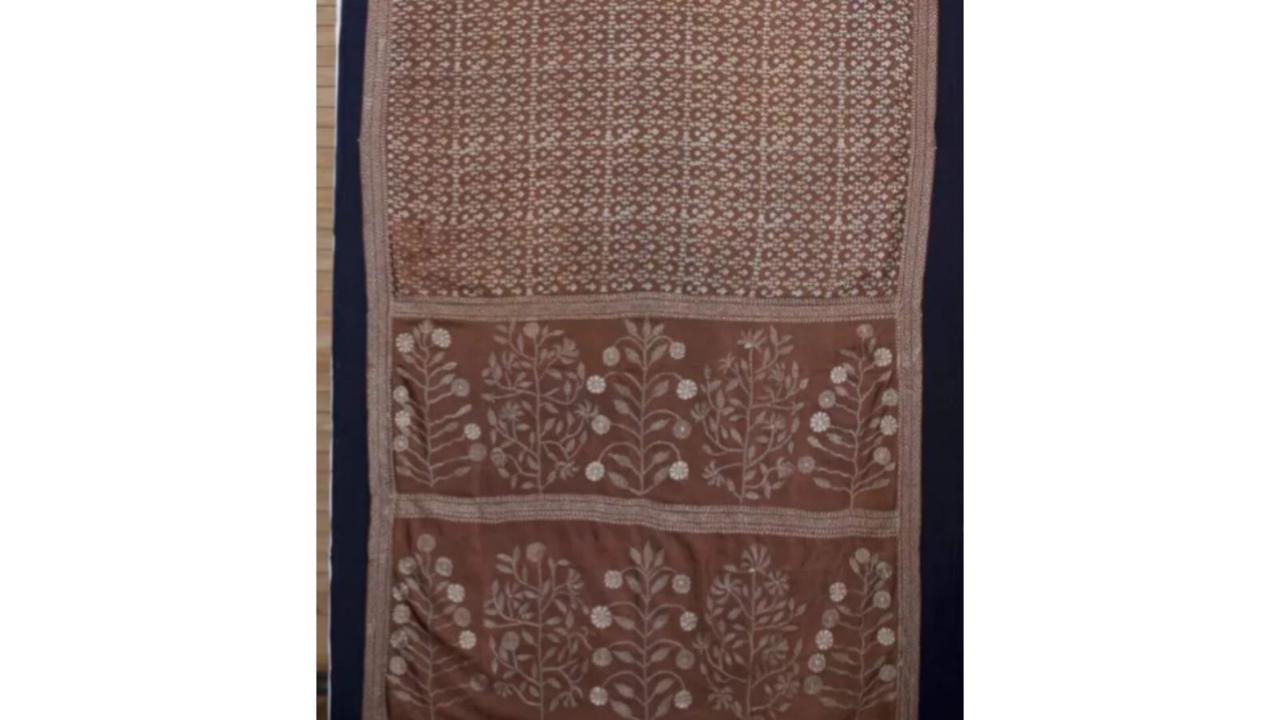

Jamdani sarees, recreated by master weavers in Bangladesh, inspired by Weavers Studio Resource Centre’s archival collection

Darshan Shah first visited Bangladesh 30 years ago to learn about natural dyes from its dedicated champion, Ruby Ghuznavi. “When I stepped into Ruby apa’s facility, it was reverence at first sight. Under her guidance, I explored natural dyes, batik and block printing,” recalls Shah, director of Kolkata-based Weavers Studio, established in 1993 with a mission “to use as many hands as possible”.

Darshan Shah first visited Bangladesh 30 years ago to learn about natural dyes from its dedicated champion, Ruby Ghuznavi. “When I stepped into Ruby apa’s facility, it was reverence at first sight. Under her guidance, I explored natural dyes, batik and block printing,” recalls Shah, director of Kolkata-based Weavers Studio, established in 1993 with a mission “to use as many hands as possible”.

Ghuznavi, born in 1935, relocated from Kolkata to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) after Partition. She earned BSc and MA in Economics degrees from the University of Dhaka, and worked as a teacher and social activist. Her experiences of displacement deepened her appreciation for handmade textiles and their global market.

In 1982, Ghuznavi launched the Natural Colour project, starting with six colours learned from Indian experts and expanding to 35 colourfast dyes, a rare feat matched by very few countries. “At a seminar on Jenny Balfour-Paul’s book Indigo, the author pointed out Ruby apa as the true expert sitting in the audience. Later in India, an expert in vegetable dyes asked me, ‘How is the Indigo lady?’—a testament to the respect that her neighbours had for her,” says Shah.

Ruby Ghuznavi is recognised as a vanguard in the renaissance of Bangladeshi handicrafts

Ruby Ghuznavi is recognised as a vanguard in the renaissance of Bangladeshi handicrafts

Encouraged by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, a pioneer in natural dye revival in India and Bangladesh, and renowned artists Zainul Abedin and Rasheed Chowdhury, Ghuznavi set up Aranya Crafts in 1990—a fair-trade micro enterprise specialising in crafts made from natural dyes.

Ghuznavi, who passed away in 2023 in Dhaka, is recognised as a vanguard in the renaissance of Bangladeshi handicrafts. “Along with artist Quamrul Hassan and others, she played a key role in establishing the National Crafts Council of Bangladesh (NCCB), and securing Geographical Indication (GI) status for Jamdani,” adds Shah.

Shah’s recounting of Ghuznavi’s impact provides a fresh and evocative contrast, if not a counter-narrative, to the recent crisis-focused reports about Bangladesh’s “fast fashion” manufacturing industry. This enriched historical and cultural retelling paints a deeper, more nuanced picture of Bangladesh’s craft, textile and design heritage, while also highlighting the shared legacy of undivided Bengal.

Darshan Shah

Darshan Shah

This perspective is further examined in Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy, an upcoming 2025 exhibition by Shah’s Weavers Studio Resource Centre (WSRC). “WSRC, a not-for-profit section of Weavers Studio, is undertaking a multi-year project to study the textiles of undivided Bengal from the 14th century to the 20th century,” explains Shah. “Despite their significance, these famed textiles have been largely neglected in academic circles. It has been a victim of the partition of the sub-continent and the recent history of India and Bangladesh. Our aim is to renew interest in Bengal’s textiles and draw attention to their current state in West Bengal and Bangladesh.”

“My deep interest in archives is to connect the dots between past and present, uncovering how much has changed and what endures,” says Dr Ritu Sethi, editor – Global InCH Journal of Living Heritage and the Asia InCH Encyclopedia.

Her chapter on Exhibiting Bengal Textiles: 1851 to the Commonwealth will feature in a book edited by Tirthankar Roy, Sonia Ashmore, and Niaz Zaman, which ties in with the WSRC exhibition launch. “I studied textiles exhibited from 1851 to 1947, spanning the colonial era up to the Commonwealth, showcased both internationally and within India. As I delved into the project, I was delighted and astonished by the profound interest in the past that was waiting to be awakened,” Dr Sethi adds.

Nakshi kantha silk saree: Hand-embroidered with natural dye batik by Ruby Ghuznavi, Bangladesh. Collection of Weavers Studio Resource Centre

Dr Sethi’s excitement is palpable when discussing Bengal’s craftwork, choosing to view it as a unified heritage rather than splitting it into pre- and post-Partition eras. “I approach creativity through a broad lens—encompassing people, culture, art, cuisine, festivals, and of course, craft and textiles. Creativity isn’t a matter of versus or competition,” she argues.

Known for her extensive work in Bengal, including Embroidering Futures—Repurposing the Kantha, and Painters, Poets, Performers—The Patuas of Bengal, Dr Sethi asserts that Bengal deserves much more attention, calling it a ‘loadstar’.”

Soumitra Mondal

Soumitra Mondal

“The golden era of Jamdani is rooted in undivided Bengal. Today, even when you find muslin or Jamdani pieces at institutions like Victoria and Albert Museum, they are labelled ‘…from Bengal’,” notes Soumitra Mondal. The Howrah-based designer, who received the National Handloom award in 2023, first gained attention with Marg by Soumitra at Lakme Fashion Week in 2007. In 2018, he introduced Bunon, a ready-to-wear womenswear line in Tokyo.

Although Mondal’s connection with Bangladesh has not involved direct collaboration with its handloom weavers, he participated in Bangladesh Fashion Week 2023, which also featured Paromita Banerjee and Rimi Nayak. “I maintain close ties with Bangladeshi designers like Maheen Khan [founder and president of the Fashion Design Council of Bangladesh].”

Soumitra Mondal’s Musafir collection showcased at Bangladesh Fashion Week 2023 featured handwoven sarees and fabrics from fine linen yarn

Soumitra Mondal’s Musafir collection showcased at Bangladesh Fashion Week 2023 featured handwoven sarees and fabrics from fine linen yarn

The concept for Epar Bangla Opar Bangla emerged from conversations with Khan. The name, meaning “this side of the river” (Epar) and “the other side” (Opar), refers to the Padma River (also known as the Ganga), which divides the Rajshahi and Murshidabad districts, forming a natural border between India and Bangladesh. “The show, envisioned by Maheen, aims to explore our shared heritage and ask: ‘Who we are?’” Mondal explains.

The project was to be a travelling exhibition at historic sites like Jorasanko Thakur Bari—the ancestral home of Rabindranath Tagore—and a comparable venue in Bangladesh, featuring three Indian and three Bangladeshi designers. “With Maheen’s family roots in pre-partition Bengal, the show intends to inform a shared history that extends beyond 77 years. However, due to the current uncertainties in Bangladesh, the plans are on hold,” says Mondal.

Dr Ritu Sethi, editor, Global InCH Journal of Living Heritage and Asia InCH Encyclopedia

Dr Ritu Sethi, editor, Global InCH Journal of Living Heritage and Asia InCH Encyclopedia

Similarly, Shah had to postpone her July trip to Bangladesh. She is developing her museum collection with master weavers from Sonargaon—Bengal’s ancient capital, recognised as World Craft City for being the birthplace of Jamdani sarees—and from Naopara and Narayangunj. “I am in regular contact with my karigars, who come from Muslim families with a long tradition in Jamdani weaving, and are all third-generation artisans. Barring minor transport issues, work is progressing well,” Shah reports.

After Partition, many skilled weavers from Dhaka settled in West Bengal; in Phulia and Shantipur (Nadia district), Kalna, Samudranagar, and Dhatrigram (Bardhaman district). These neighbourhoods have since become key centres where Indian designers develop textiles like Jamdani, Tangail, jacquard, and muslin.

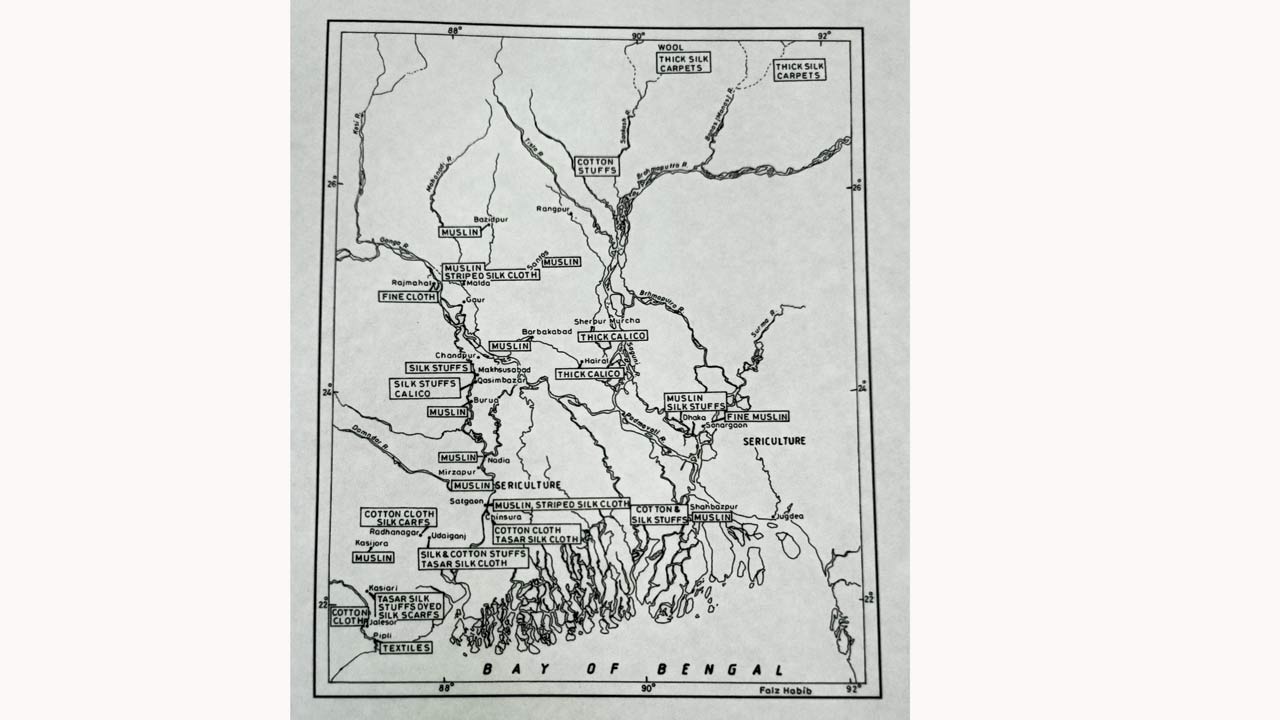

This textile map from Sushil Chaudhuri’s book Prithibir Tantghar (2018) illustrates the textile varieties produced across Bengal (in the broadest historical sense) during the 17th and 18th centuries. Pic Courtesy/Weavers Studio Resource Centre

This textile map from Sushil Chaudhuri’s book Prithibir Tantghar (2018) illustrates the textile varieties produced across Bengal (in the broadest historical sense) during the 17th and 18th centuries. Pic Courtesy/Weavers Studio Resource Centre

What makes a journey to Bangladesh indispensable? “Without it, I would have missed the essence, quality, originality, and generational depth of their craft. Their nimble hands, singing traditional songs while counting warp and weft, are irreplaceable. As someone who values craft beyond borders, I don’t think I could have gained this level of insight and connection if I had stayed only in Phulia,” reasons Shah.

Also Read: ‘Bangladeshis spend 2-3 billion USD annually on textiles from India, including handlooms’

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!