As draconian UAPA ensures freedom eludes the 69-year-old rights activist even after 2 years, Sahba Husain, his partner of 26 years, suffers immensely but keeps the flame of love and resistance burning

Navlakha was denied a replacement of his spectacles that were stolen and books by PG Wodehouse until media, court interventions compelled authorities to relent. File pic

Writer Sahba Husain rattles out from memory all the dates of twists and turns during her ongoing struggle to keep the flame of love and resistance burning. She remembers the date (August 28, 2018) when the Pune Police raided her home to arrest her partner and human rights activist Gautam Navlakha, an accused in the Bhima Koregaon case. Sahba can recall what petitions were filed when in different courts—and the dates of each verdict.

Writer Sahba Husain rattles out from memory all the dates of twists and turns during her ongoing struggle to keep the flame of love and resistance burning. She remembers the date (August 28, 2018) when the Pune Police raided her home to arrest her partner and human rights activist Gautam Navlakha, an accused in the Bhima Koregaon case. Sahba can recall what petitions were filed when in different courts—and the dates of each verdict.

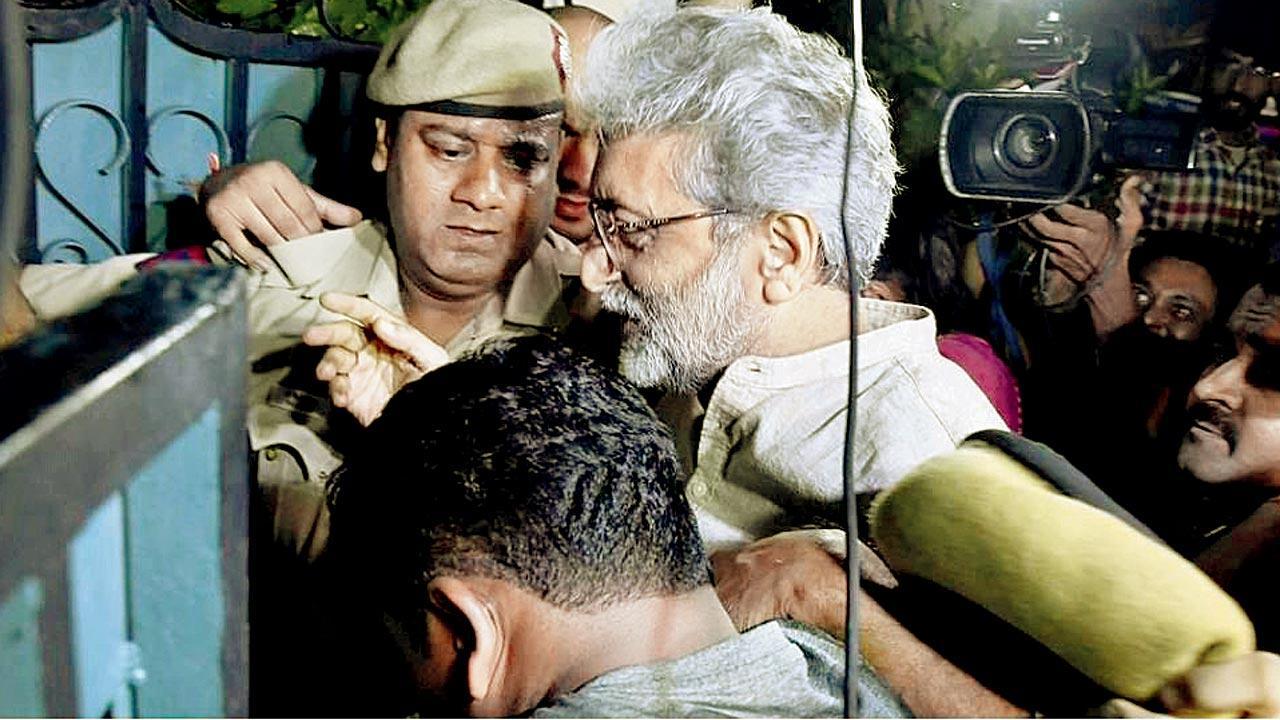

Etched in Sahba’s memory is April 8, 2020, the day the Supreme Court gave Navlakha a week to surrender before the National Investigation Agency. As the thrum of life sounded like a guitar out of tune, she remembers, with admiration, Navlakha writing his last media column on April 13. A day later, she bid him goodbye as he disappeared into Delhi’s NIA headquarters.

It is obvious Sahba has rewound and replayed the scenes of the last four years over and over again, to draw strength from what she had been through in order to endure what may still lie ahead. Her anxiety springs from the question: When will Navlakha win his freedom and they be united again? Call it the suffering of separation, made unbearable because it has been scripted by the State, which invokes the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act to torment bravehearts who articulate their opposition to its imperious ways, as Navlakha has done through most of his life.

But then, her eyes suddenly acquire a sparkle and voice a joyous ring as she narrates the happenings of November 24, 2021. She had come to know that Navlakha, on that day, would be brought from Mumbai’s Taloja Jail to JJ Hospital for a checkup.

He saw Sahba standing in the corridor. He lunged forward and hugged her.

They hugged long enough to prompt the constable to ask: Who is she? “Yeh to meri zindagi hai—she is my life,” replied Navlakha. Since the constable looked befuddled, Navlakha said, “My wife”. As he underwent routine tests, Sahba teased, “Hey, in our 26 years together, you have never called me your wife.”

Sahba is not Navlakha’s wife. Theirs is a live-in relationship. She is 70 years old. He is 69. Both have children from their first marriages. Both have grandchildren. Living in different corners outside India, the family incessantly worries over Sahba and Navlakha, each battling alone their sadness of separateness.

What do they know of love who only hate know?

Their love was born in the crucible of activism. It involved agitating together against the Babri Masjid demolition, fighting for the rights of Kashmiris and Adivasis of Chhattisgarh, faulting the State for siding with corporate giants and its penchant for militarising Indian society.

Sahba’s inheritance is activism. Her father, Alam Khundmiri, was elected, in 1939, as President of the Comrades’ Association in Nizam’s Hyderabad. The organisation was a counterfoil to the Razakars, who wanted Hyderabad to accede to Pakistan. A peasant rebellion broke out under the aegis of the Communists, who, after the annexation of Hyderabad, were ruthlessly suppressed by the nascent Congress regime. Khundmiri was dubbed a “kafir”.

The kafir’s son, Javed Alam, who taught at Delhi’s Salwan College, married Jayanti in the 1970s. Economist Prabhat Patnaik reminisced that the Jana Sangh pasted posters accusing Alam of abducting her, evident from their line: “Where is Jayanti?” The couple was summoned by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Jayanti told Gandhi that she had married Alam of her own volition.

Politicians come and go, talking of love jihad. But now the Prime Minister keeps silent.

Yet the family’s past did not prepare Sahba for the trials and tribulations of the changing times. For instance, on November 12, 2019, Sahba’s book, Love, Loss and Longing in Kashmir, was to be launched. On the same day, within 15 minutes of the Pune Sessions Court dismissing Navlakha’s application for anticipatory bail, the Pune Police swooped down on her apartment to arrest Navlakha, who was not at home. Sahba refused to cancel the launch, for it would have implied letting the State harass them. Navlakha returned home two days later, after the High Court gave him protection from arrest.

On November 26, 2021, she was not allowed to meet Navlakha in Taloja, after it was opened, post-COVID, to visitors. The reason: she was not his wife but partner, a legally flawed argument the NIA court subsequently set aside. Quite ridiculously, Navlakha was denied a replacement of his spectacles that were stolen and books by PG Wodehouse until media and court interventions compelled jail authorities to relent.

The harassment of four years has had Sahba overcome shock and disbelief, and the very deep grief that clung to her skin after the incarceration of Navlakha. She cried and cried until her tears dried up. “But sadness still overwhelms me at times,” she says.

Narendra Modi recently suggested that expeditious bail be granted to undertrials. Jumla? Sahba would make the riposte: Just how many years must a person spend in jail for the system to declare he is innocent? Until that happens, Sahba will continue to sign off her letters to Navlakha thus: “I love you.” Take it from Sahba: Love is defiance.

The writer is a senior journalist

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!