Alan Arkin passed away last week; there are greater actors, even more famous ones, but no one can match his longevity—a 70-year career, across TV, cinema and stage

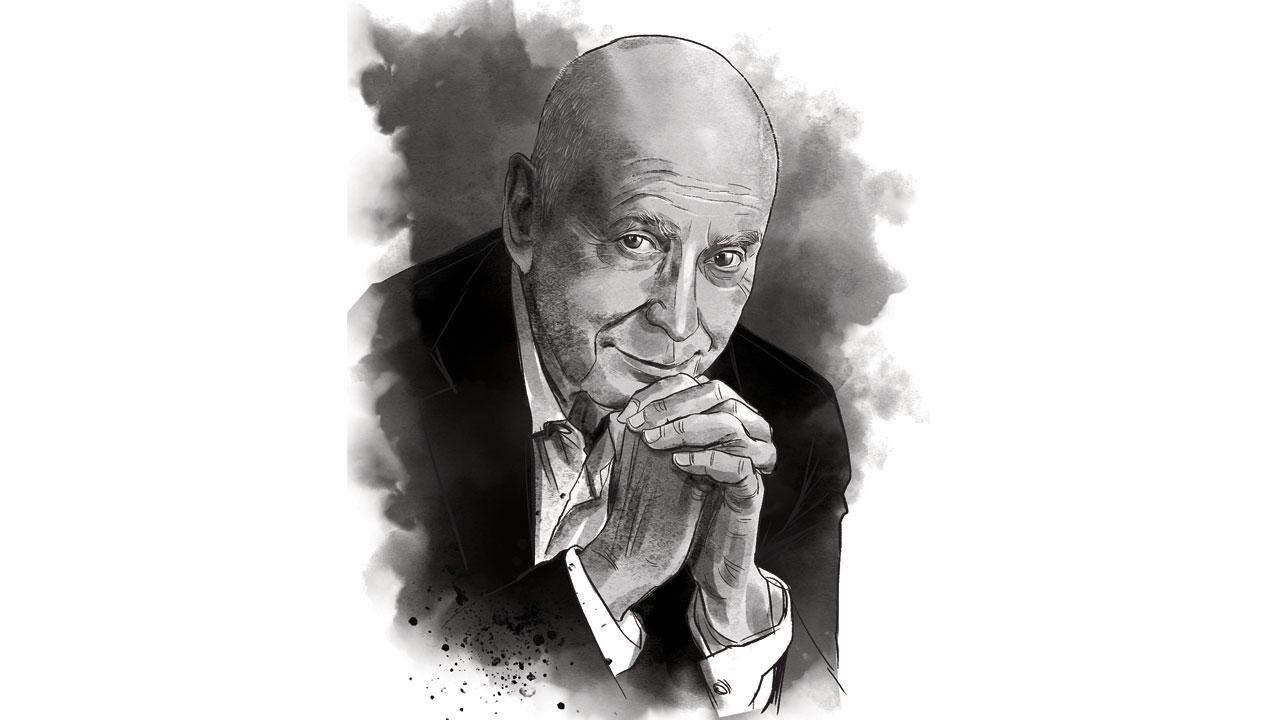

Illustration/Uday Mohite

A real loser is one who is so scared of not winning, he doesn’t even try—Alan Arkin’s Edwin Hoover in Little Miss Sunshine.

A real loser is one who is so scared of not winning, he doesn’t even try—Alan Arkin’s Edwin Hoover in Little Miss Sunshine.

Alan Arkin passed away last week; there are greater actors, even more famous ones, but no one can match his longevity—a 70-year career, across TV, cinema and stage.

In 2006, Mr Arkin, finally got a well deserved Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Little Miss Sunshine.

He’d played such a role before, crusty, curmudgeonly, eyes dancing with amusement, armed with a distinct Brooklyn accent—but this time, aged 72, audiences and the Academy finally woke up to this intelligent comedian displaying his rich gamut of wares. Films like Argo in 2012, and TV shows like The Kominsky Method (2018-19) followed.

He had a gift, to display radiant happiness which could dissolve into rapier—like rage, with a tiny shift of vocal calisthenics and minimal facial shift. Arkin had that ability, because he always believed completely in the material, and trusted his craft. But humour above all else.

Take a scene from The Kominsky Method on Netflix, he and Michael Douglas’ character are coffin-hunting— Arkin’s late wife’s instructions are quite specific, she wished to be buried in a casket made of driftwood or sunken ship timber. The undertaker, nonplussed by this unusual request, keeps offering more convenient options, including eco-friendly ones, but not driftwood or timber, annoying Arkin’s character.

“How about cardboard?” he was asked, by the undertaker

“Whaaaat? Why not bubble wrap, then?” he counters, sarcastically.

You see Arkin’s anger rising, stemming from the pain of loss, and the stupidity of suggestions. The line between laughter and lament boils over as he hollers, “I’m not burying my wife in cardboard even if it’s bio-degradable! Cardboard boxes are what you put a plant in when you don’t want it to leak in your car!”

The ability to project pain, while still leaving your audience in splits is a talent that Arkin possessed.

I’ve studied actors very closely for a number of years. They vary between the show ponies and the subtle artistes, the Method specialists and the Classicists, the Sanford Meisners’ vs the Lee Strasbergs’, the Stanislavskis’, many differing techniques, but there are only two big truisms, in my humble opinion.

1. There are the good actors and the not-so- good, the ones that try too hard, ‘see how much effort I’m putting in to get into the skin of the character’ and the ones that are effortless in their portrayals—the best ones disguise the hard work, so the performance seem so simple.

2. There’s another category, actors that don’t play too far from themselves—Is there a truth to your performance, do you believe the dialogue you are uttering, truly make it your own.

Arkin internalised both these truisms.

He played the roles close to his comfort zone, he didn’t overstretch, didn’t overact, followed the “acting is reacting” principle, but was always believable, and watchable.

If truth be told I’m not as mindful about what an actor will do with a role, it’s what he/she will do with a line, a paragraph, a phrase, a speech, a monologue… how he will twist, rework them—Arkin gave me a feeling that he had a great say in what lines he uttered, sure he respected screenwriters, he worshipped dialogue, appreciated great writing , but he made those lines better, threw them away when required, punched them, let them be, pulled them back, smiled them, shouted them, whispered them, tragedy, comedy, thriller, were tackled seamlessly in his trademark speech delivery.

His anger and his joy and his bewilderment were tiny whiskers away from each other.

Travel well, sir...

Rahul daCunha is an adman, theatre director/playwright, photographer and traveller. Reach him at rahul.dacunha@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!