Stories from five old DN Road buildings in the week of Dadabhai Naoroji's 100th death anniversary

The Lawrence & Mayo Building at DN Road offers a wonderful example of conservation guidelines being followed. Pic/Bipin Kokate

I was lucky. To cut my teeth in journalism on the top floor of a building as splendid as the street it graces. Pure privilege to proof text gazing from Indo Saracenic arched windows decking the Old Lady of Bori Bunder. Even with tight deadlines of a 72-page national weekly to edit by Saturday afternoons, there was no way to resist Dadabhai Naoroji Road. We lunched at Bengal Lodge after issues subbed crisp for press, shopped for kurtas at UN Pursram with salaries warm from wooden boxes dispensing them, browsed through stationery at Chimanlal's in a pre-Net age when written notes were romantic pleasures.

I was lucky. To cut my teeth in journalism on the top floor of a building as splendid as the street it graces. Pure privilege to proof text gazing from Indo Saracenic arched windows decking the Old Lady of Bori Bunder. Even with tight deadlines of a 72-page national weekly to edit by Saturday afternoons, there was no way to resist Dadabhai Naoroji Road. We lunched at Bengal Lodge after issues subbed crisp for press, shopped for kurtas at UN Pursram with salaries warm from wooden boxes dispensing them, browsed through stationery at Chimanlal's in a pre-Net age when written notes were romantic pleasures.

This genteel address on the Espanade resulted from the Fort ramparts demolished by 1860.

Exquisitely detailed edifices expanded the stretch known as Hornby Road, for William Hornby, Governor of 1770s Bombay. Their Neo Classical and Gothic Revival facades, often crowned with pyramidal roofs, were linked by continuous 15 feet-broad pedestrian arcades. Unlike European Gothic, which shuttered out the cold, Bombay buildings were designed to let in our more temperate weather.

Looking up from cobbled pavements, I have clear preferences. How do my five favourites stack up against the spectacular Victoria Terminus and BMC headquarters? They whisper riveting tales from elegant, if now faintly elegiac, interiors.

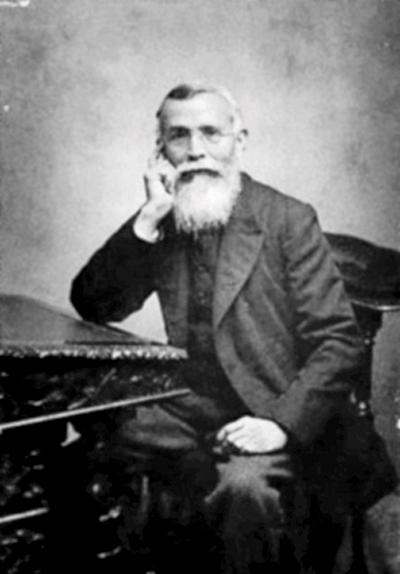

Dadabhai Naoroji. Pic/wiki commons, national portrait callery

"Buildings are like people: their faces mirror their experience," says culture critic Justin Davidson in a podcast. Those on Heritage Mile, anchored north by Crawford Market and south by Flora Fountain, wear the composed air of witnessing an eventful past. The oldest, trying valiantly to withstand subway drilling today, is 1817-erected Eruchshaw Building. Consultant physician and sixth generation doctor, Avimoy Hakim, shares that her great-grandfather, Dr Eruchshaw Hakim, acquired the property as a trio of tall structures from as many landlords. "It made an interesting hodge-podge house to grow up in," recalls Avi's 92-year-old aunt, Eruchshaw's granddaughter. "With theatres, banks, libraries, shops like Evans Fraser and Whiteway & Laidlaw (advertised as 'The First Store in the First City') it was a complete world within itself."

A lift in a cage without a shaft, dramatic rear stairway winding up to a Yin-Yang mosaic and pink garland designs on green wall tiles, ensured Eruchshaw Building was the evocative location for movies like Pestonjee and The Guru. Its well water helped douse fires in the area, including some of its own. In the blaze 23 years ago, India Book House publishing director Padmini Mirchandani lost original artworks of 1966-introduced Amar Chitra Katha collections. The damage claimed luminous examples daubed in the typically soft brushstrokes of Ram Waeerkar who illustrated cult titles like Mirabai and Krishna. "That left Anant Pai devastated," says Padmini, referring to the creator of this series and Tinkle Comics, discovered by her father GL Mirchandani.

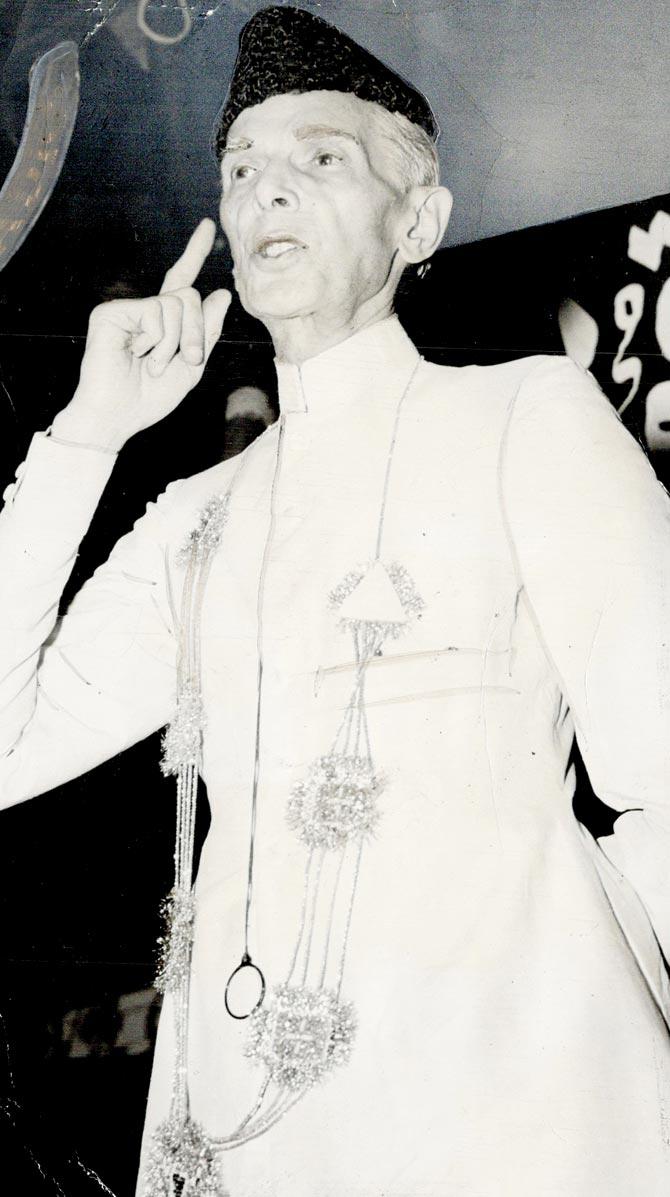

Among Lawrence and Mayo's more famous clients was Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who brought in his signature monocle for repair. Pic/Getty Images

"Bombay was a beautiful city everyone wanted to take pictures of with their cameras," Eruchshaw Hakim's nonagenarian granddaughter keeps repeating. Across the road from her ancestral seat, Kodak House was the ultimate photo mecca of the day. Belonging to the Tatas in 1913 when Kodak moved in (then sold to Deutsche Bank and presently Cathedral and John Connon School), the building offered unique services. "From the Suez to Singapore, it was the only spot developing Kodachrome film, sent to the Worli processing unit - a fact they were very snooty about," says ophthalmic surgeon Burjor Banaji from Navsari Building three gates away. "I saved pocket money for precious images of my Himalayan treks, but their prints, back after six long weeks, weren't always properly done."

Kodak manager Mehernoz Maloo describes the building in which he began his career in 1988. The darkened basement cold room, warehouse, shop and lab used over two storeys of self-contained Kodak office space, connected internally with wrought iron spiral steps and an elevator unusually open on three sides. On the third floor was the Naval Seamen's Club, the docks situated near enough.

Possibly the oldest functioning lift in the city must be the wood-panelled, crankshaft-operated one in red brick Navsari Building. It is a been there-done that lift, dropping celebs like Sachin Tendulkar and Shah Rukh Khan to Dr Burjor Banaji's fourth floor clinic with blithe familiarity. This is where his grandfather Burjor and father Phiroz, eye surgeons of repute, worked from 1924. The Tata head office, named for Jamsetjee Tata's native town, Navsari Building was built in 1903, the year Bombay got electricity and the Taj. The Kotaks bought it from the Tatas in 1928.

Another three-generation medico clan the building boasts is that of ENT surgeon Piloo Hakim. She, her father Dr Rustom Cooper and daughter, Dr Arnaz Soonawala, specialised in the same field. On the second floor with them since 1922 is The Iran League. Vispi Dastur, its president, explains that the organisation used to administer orphanages and dharamshalas in Iran, besides sending hundreds of Parsis from India and Pakistan there for employment during the Shah's reign. "We had close ties," says Dastur, who remembers a Bombay meeting with Iranian Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda, executed one April midnight just after his country's bloody 1978-79 revolution.

Eruchshaw Building, the oldest charismatic structure on the street since 1817, has had its facade restored after a fire in the mid-1990s

Navsari Building's iconic shop, James & Co., was the Furtados of its time. My 93-year-old father bought his earliest LP here around 1940: Mozart's Violin Concerto No. 5 in A Major played by Jascha Heifetz, the mere mention of whose name still visibly lights him up.

Both music lover and book buff, dad directs me two buildings onward to Macmillan Building, or Lawrence & Mayo building. Its top floor, home to Harold Macmillan's publishing firm, was where that first British Prime Minister to visit India put up in the city. Shorn of billboards and transformed according to architect Abha Narain Lambah's recommendations, this handsome twin-domed Renaissance-style building reveals wooden rafters and sensitively rearranged signage. Established in 1877 by two Jewish family friends, Lawrence and Mayo, this company, opticians to the burra sahibs, was led here by LH Aliston. Isodore Mendonsa, self-taught in the optical trade, took over from Aliston, to be succeeded by son Robert who consolidated the business.

At 85, Robert Mendonsa is chipper and charged as he recalls engaging moments on the job. Among famous clients, MA Jinnah brought in his signature monocle for repair. "I want an identical piece. Be careful, don't make it and break it," he drily said. The mystery of the missing gold-plated spectacles cropped up too. After a few disappeared, Pereira the foreman stayed back in the workshop one night to investigate. At dawn he heard a flutter on the window sill. A crow hopped in, picked a pair of gold-rimmed glasses in his beak and flew to a nest woven at Lloyds Bank building next door. A whole cache of shiny client-ordered frames was retrieved from the winged thief.

The then Tata-owned Navsari Building, named after the native town of Jamsetjee Tata, was erected in 1903, the year Bombay got electricity and the Taj Mahal Hotel. Pic/Burjor Banaji

Then there were the good doctors padding clever paths inside Thomas Cook Building. Radiologist Sorab Sidhva has a fund of anecdotes about his jovial father Dr Jimmy Sidhva's initial days in the profession. The senior Sidhva, who went on to be the only Asian on WHO's World Commission of Neuroradiology in 1960, had a thin practice on first occupying fourth floor rooms of this building of keystone and cornices. He and second-floor neurosurgeon Dara Karanjavala left word with their receptionists to summon them down from the terrace, where they played cricket, if a patient did finally walk in. "Before they became the giants they did, they hid tea and biscuits beneath a green cloth on a wheeled trolley - with small surgical instruments jutting to slyly suggest a tray piled with instruments!" Sorab laughs.

Thomas Cook Building is the Harley Street hub of Dadabhai Naoroji Road. Along with the Sidhvas, it houses clinics of the redoubtable Dr Farrokh Udwadia, his pulmonologist son Zarir and surgeon brother Tehempton Udwadia. Stalwarts with them included neurologist Freny Kohiyar, physicians Kekobad Minocher Mody and OP Kapoor, Guinness Book nominee for record medical lectures. Every few months they trooped out together to dine at The Other Room of Ambassador Hotel, on what was called Cook's Night.

Round the corner, Talim's bronze statue of the Grand Old Man of India himself fronts the Oriental Building junction. Community scholar Marzban Giara points to the pedestal sides. The west portrays Dadabhai Naoroji at a House of Commons session addressed by William Gladstone. It is the east panel I find exceptional: showing the statesman who espoused women's education, lead a group of young ladies to Saraswati Mandir. Four fine inscribed words read – "Mothers really build nations".

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at mehermarfatia@gmail.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!