After winning the prestigious Berkeley Rupp Prize for her work with slum communities in Mumbai for nearly a decade, the founder of Community Design Agency is now focussing on how she can instil an ‘understanding of space’ among students at Berkeley

Architect Sandhya Naidu Janardhan (centre) speaks to mid-day about her contribution to slum community housing in Mumbai. Pics/Shadab Khan

Sandhya Naidu Janardhan, an architect who has been working with slum communities in the city for almost a decade, recently won the Berkeley-Rupp Architecture Professorship and Prize in recognition of her work. The bi-annual award by the University of California and Berkeley College of Environmental Design (CED), which includes a $100,000 cash prize, is given to a distinguished practitioner or academic who has made a significant contribution to communities, gender equity, and environmentally sensitive use of resources.

ADVERTISEMENT

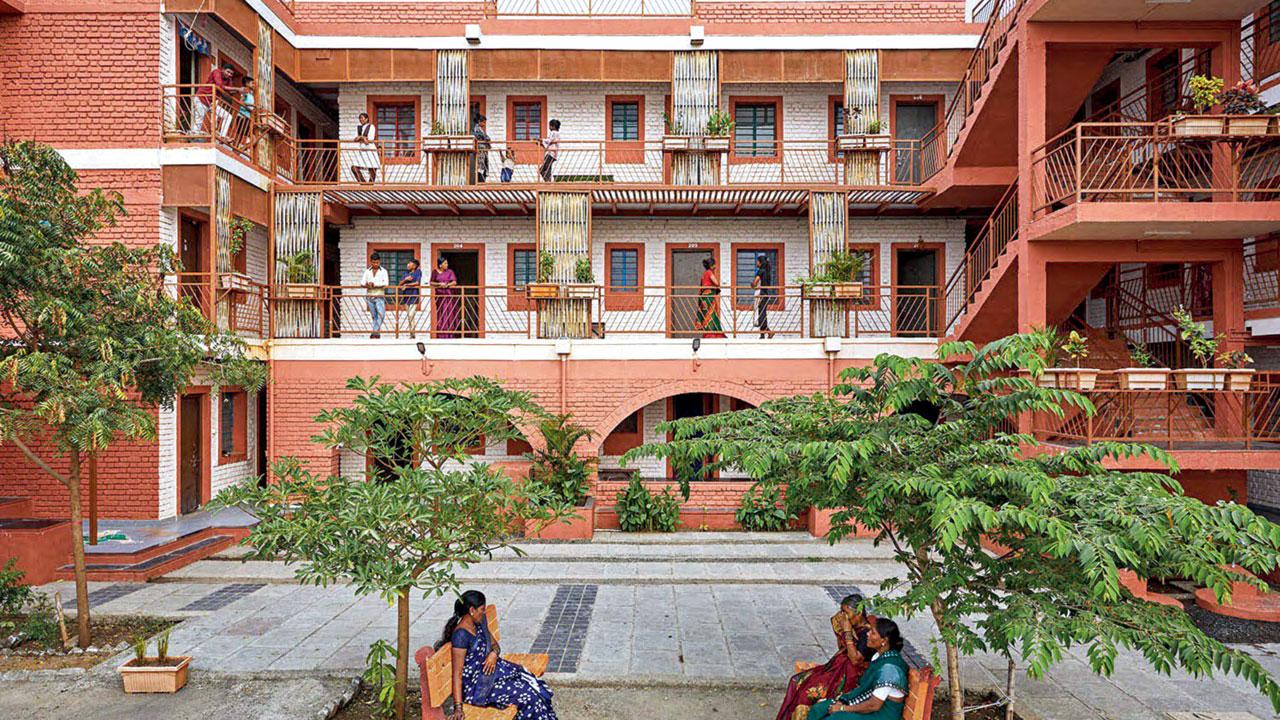

The Sanjaynagar Slum Redevelopment Project provides climate-resilient, sustainable homes to 298 families, uplifting generations out of poverty and improving their health and wellbeing

Naidu founded the Community Design Agency (CDA), which includes a team of architects, engineers, business professionals, community planners, and artists. The agency works with marginalised communities and collaborates with civic and government bodies, apart from corporations and other philanthropic entities. One of the flagship achievements of CDA was creating a community library ‘Kitab Mahal’ in Govandi and subsequently hosting the Govandi Arts Festival in the area with large-scale community participation.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

Your work aims to address the spatial inequalities in urban life. What does that mean in Mumbai’s context?

The term extends beyond physical access to a house and looks at the social stigma associated with the area where that house is situated. In the context of Mumbai, as the city expanded and attracted crowds for better opportunities, housing and basic amenities were not readily available, leading to the emergence of slums. Beyond access to sanitation and drinking water, the term addresses issues like access to outdoor spaces for women and children, highlighting how women navigate from outdoor to public spaces and their experiences within them. Let’s look at a relocation and rehabilitation colony like Natwar Parekh Compound in Govandi, where living conditions are artificially created for thousands of people, this neighbourhood comprises 61 buildings on just five hectares of land, housing over 5,500 apartments, each only 226 sq ft — insufficient for families of five to eight people.

At the heart of the initiative’s process is centering the community’s needs and aspirations, and ensuring everyone gets a say in how their spaces should be designed

While policies regarding such colonies have evolved, with units now up to 500 sq ft, in this particular colony, buildings are densely packed, with 80 per cent apartments lacking sunlight and natural ventilation. This inequality affects health and restricts employment opportunities. Employers stereotype such neighbourhoods, regardless of the qualifications of applicants. Many individuals, despite having permanent homes, hesitate to provide their address.

Why is this inclusive approach not taken into account by state authorities like SRAs?

There are issues with Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) structures, which are riddled with terrible living conditions for the residents. However, it is not only the authorities that are to blame for the lack of an inclusive approach. This is how architecture and planning have evolved in terms of how cities and neighbourhoods are built. Inclusivity in design means understanding the perspective of the end-users very well. If that is achieved, then what is offered will be more effective. An analogy can be drawn to discussions about ‘user experience’ in the technology space, where there is an effort to understand people’s needs.

Sandhya Naidu Janardhan

There is no ‘magic bullet’, but if we want a better city and sustained transformation for those who are marginalised and minorities, it is very important that municipal corporations and planners engage with the communities. This will make our policies and decisions on spending more effective.

What do people commonly misunderstand about slums in Mumbai?

Many do not realise that there is a strong social fabric within the slums. People have developed and cultivated this over decades of living together, celebrating together, and also fighting with each other and then reconciling through that. It is a community; this is the social side of it. The other perception is of ‘poor people’ who do not have agency. Someone may be financially poor, but that doesn’t make them culturally poor. Slums are not places that are lacking in every aspect; it is the physical infrastructure that is lacking.

It is crucial to understand that people like me are not romanticising slums. All we are saying is that we cannot be dismissive of opinions on communities. Let’s take Dharavi redevelopment, the general idea is that it is a real estate problem that must be solved, which is not the case. It is this incredible microcosm, a city-within-a-city with diverse communities living there. A top-down approach cannot work with places like Dharavi where the community has been supporting themselves for decades; it will only lead to more insecurities.

The highlight of your career is the Sanjaynagar slum redevelopment (Ahmednagar, Maharashtra) where residents contributed R1 lakh for a house. Do such self-financing models work better than the SRA model?

We focused on establishing equitable communities rather than just providing housing. We considered various parameters such as livelihoods, access to social spaces, sustainability, etc., and consulted with the community on how to achieve these goals. We aimed to set new benchmarks for what slum redevelopment could look like. A simple way to gauge whether a project has its heart in the right place is by asking: ‘Could I live in this place?’ The first building we created is the kind of place anyone would be comfortable to live in. For such structures, financing from the residents is necessary.

It’s unfair to burden slum dwellers with the costs of the processes we’re setting up for consensus-building and participatory design. This is where philanthropic players step in, sharing some of the costs. Once consensus is reached among residents on what kind of neighbourhood they want; the project becomes eligible for government subsidies and private investment.

It took months-long work to convince residents to contribute R1 lakh as it is a big amount. But it changed the dynamic among stakeholders, as every family became invested, making their voices stronger. This resulted in better planning and increased property values. Ultimately, the government’s goal is to elevate everyone to the middle class. There is no sales component here, unlike the SRA projects, so whatever we are continuing to build is for the community.

The prize you won also includes teaching at The College of Environment Design, Berkely. What are your plans for it?

It will be a seminar course that I will be teaching in a workshop-mode and not a lecture series. It will focus on how students can bring about understanding of space as an impact on social issues. Like space at the intersection of health, gender equity, livelihood, safety, inclusion, climate change. We cannot look at architecture merely as a product; at the moment, architects serve a small percentage of the population. It will be a multicultural group of students, and the course has been opened up to other departments in the university. I am also keen on bringing on board the voices from the communities I have worked with and my peers in the US have worked with.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!