The emotional, physical and fiscal reasons many women find it difficult to walk away from abusive boyfriends, partners and husbands

Shraddha Walkar, 26, had told friends she feared for her life. Illustration/Uday Mohite

Why did you not leave your partner?” — this is a common question that survivors of violence in relationships face. But the fact that the estimate of intimate partner violence against women in the South-Asian region is as high as 33 per cent—according to a 2018 WHO study—is a quantitative indicator of the various factors that compel them to stay silent and feel trapped by these ties.

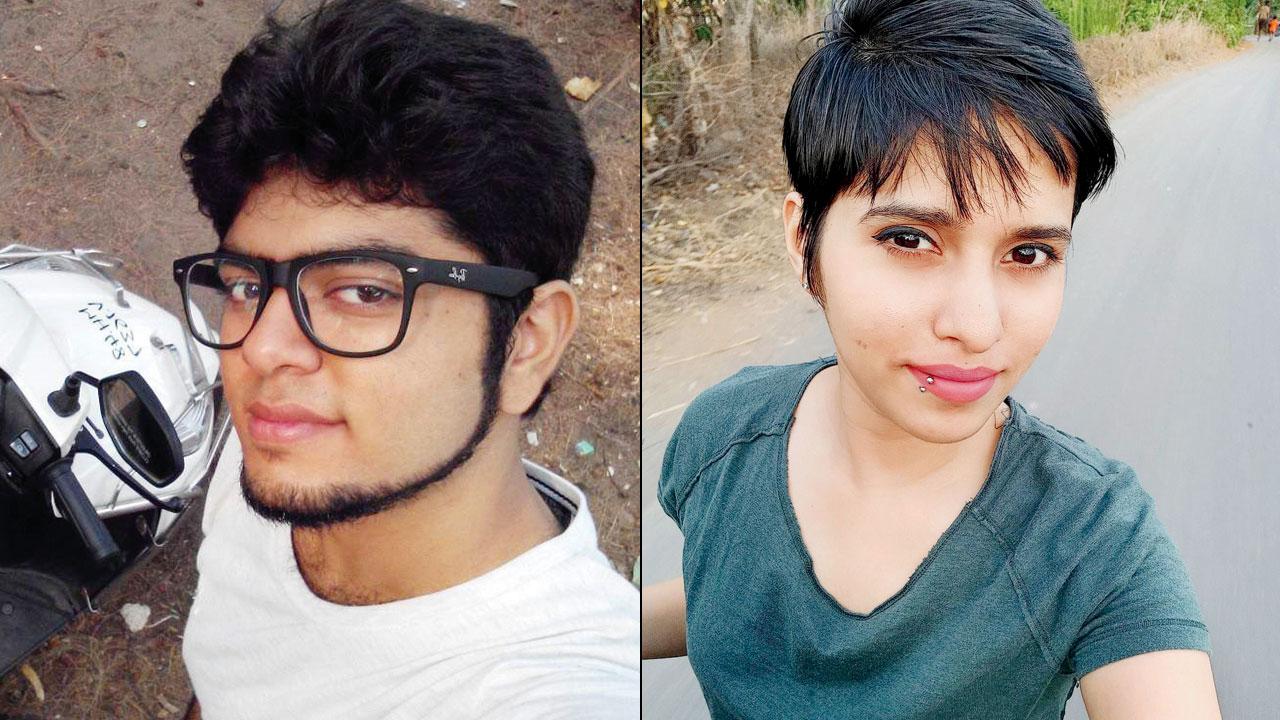

Aftab Poonawala. Pic/Facebook (right) Shraddha Walkar. Pic/Instagram

The gruesome murder and dismemberment of 26-year-old Shraddha Walkar, a Vasai resident, by her 28-year-old live-in partner Aftab Poonawala, has once again prompted the urgent need to spread awareness about abusive relationships. Experts share reasons why people find it difficult to exit abusive (physically, mentally, emotionally, verbally and sexually) relationships, patterns of abuse, and ways to seek and extend help.

Stop victim-blaming

Often, the onus of the situation or the blame is placed on the survivor. Suvarna Varde, a psychologist and relationship counsellor, highlights that being unaware of the threat cannot be a reason to blame the survivor. “It’s important to understand that a person, before becoming a survivor of any abusive or toxic relationship, does things which they feel are right at that point in time. However, offenders behave intentionally and are aware of their actions. The conscious behaviour of the abuser has to be questioned.”

Signs of abuse include controlling behaviour, disrespect and violence

Dr Meghna Singhal, a trauma-informed psychotherapist and parenting educator, explains the psychological reasons behind victim-blaming. “It happens because we see ourselves as being very different from the survivor to confirm our invulnerability to abuse.” To counter this approach, as it prevents survivors from speaking up, she highlights that the focus must be on the perpetrator since abuse is never about individual actions which incite the abuser to hurt their partner; it is about the abuser’s feelings of entitlement. Arouba Kabir, a mental health professional and founder of Enso Wellness, also points out the lack of awareness about what a healthy and unhealthy relationship look like, and the role of media and cinema in portraying romantic relationships where possessiveness and jealousy are glorified.

Recognise the patterns

Swapnil Pange, a psychologist and marriage therapist, notes that abusive behaviour doesn’t develop overnight, and that identifying warning signs and ways to tackle them should be included in training provided at schools, colleges and workplaces. According to Pange, the common red flags include lying, having multiple affairs, encroaching on personal space, denying individual rights, emotional neglect or indifference towards the partner, and blaming the partner or making them feel guilty after fights. Other warning signs include violating privacy, isolating the survivor from family and friends, controlling behaviour, any form of disrespect and humiliation towards the survivor, possessiveness and threatening or harming the survivor. It’s important to understand where to draw the line on compromise, Varde reminds us. Positive compromise is mutual and benefits relationship goals; it does not include surrendering, giving up one’s values, self-respect, family and personal relationships.

Quitting isn’t easy

Among the reasons why survivors may find it difficult to quit toxic and abusive relationships are issues with finding a safe place to live in, lack of support, finances and resources, affected self-esteem, threatening or blackmailing by abusers, the social stigma attached to domestic violence and divorce. Disha Manchekar, a psychologist and founder of Innate Mind, tells us that the first, and most difficult step, is acknowledgement. She lists reflective questions that can help one come to terms with the situation: Do I feel safe around my partner? Can I openly voice my opinions without fear of getting hurt or humiliated? Do I have the freedom of making choices for myself?

Suvarna Varde, Swapnil Pange and Dr Meghna Singhal

Suvarna Varde, Swapnil Pange and Dr Meghna Singhal

Singhal notes that exiting an abusive relationship isn’t as easy as walking out the door; one can have an unhealthy emotional attachment to the abuser, which is termed a trauma bond. This refers to cyclical and manipulative patterns of assurances of love and abuse by the abuser, which make it hard for the survivor to break away.

She highlights the need for a safety plan when exiting a relationship. It includes an informed person who one can contact for help, a safe place to go to, things to carry, and accounting for the risk of harm during the break-up and ways to navigate it. “It’s natural to miss an abusive partner. But it doesn’t mean that you should be with them; you leave because the bad outweighs the good,” she reminds us.

Support your child

As parents, ending communication or disowning your child if you don’t approve of their partner and choices cuts off support and can expose them to vulnerabilities. Sexuality educator Apurupa Vatsalya notes that it may be hard for parents to not be reactive as the job of parenting comes with its own set of difficulties. In such cases, parents can start by holding space for their feelings. “As long as your child isn’t actively harming someone, it is crucial to offer them unconditional love and support. You can express discomfort but let them know that you’re always there for them. This will allow children to come to parents in case they’re facing abuse, and they will have a stronger sense of self, community and self-esteem. Seeking therapy and mediation as a family is a great option,” she adds.

(Left) Disha Manchekar; Arouba Kabir

Help a friend

Vatsalya lists warning signs to look out for as a friend and how to act on them:

>> Look for visible bruises or abuse in the form of neglect and exploitation. Sudden change in behaviour (withdrawn or unwilling to meet) could be indicative of distress.

>> Inquire about their well-being in a gentle, non-intrusive manner.

>> Try to create a safe space for someone to share without the fear of judgement. Beli-eve and validate them. Offer active participation in the co-creation of a safety plan.

>> Respect their decisions on how they would want to cope with their circumstances.

33%

Estimate of intimate partner violence against women in South Asia, as per a 2018 study

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!