A London-based professor researching the evolution of Hindustani music during the colonial rule, credits the last king of Awadh for his experimental and innovative pursuit of music

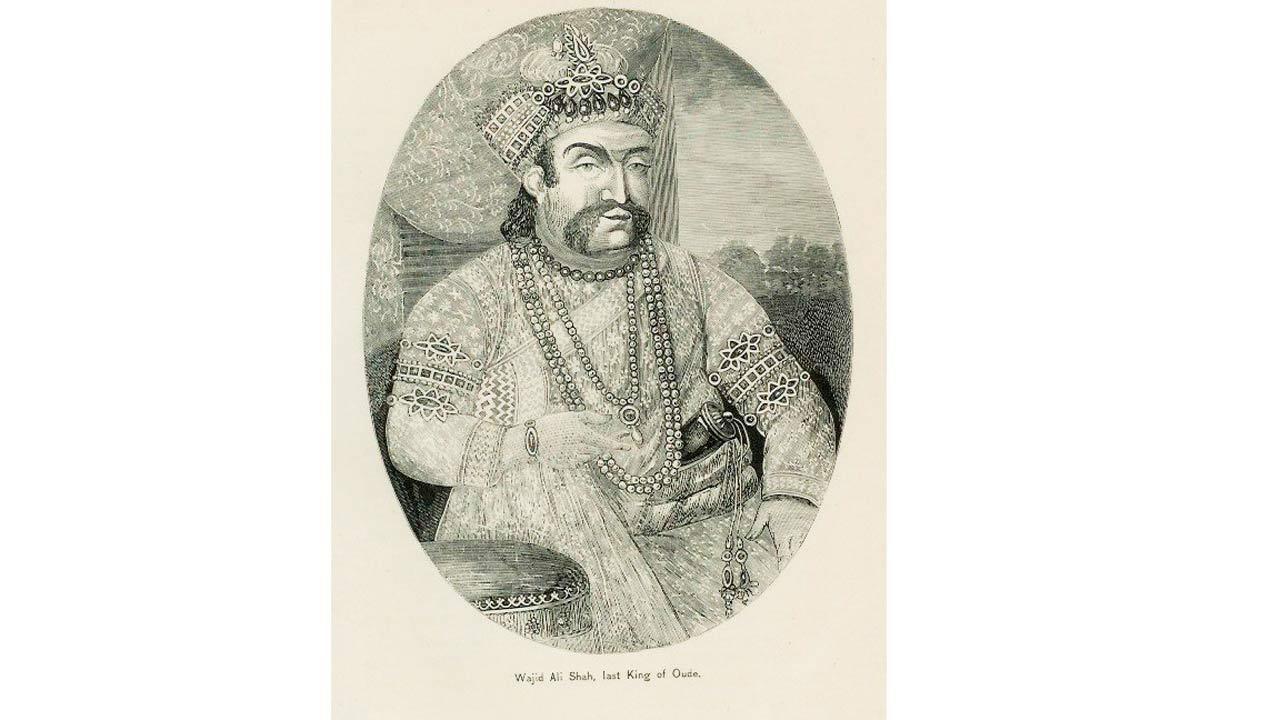

Mirza Wajid Ali Shah was a singer, dancer, and played the sitar and drums. His courts, says Williams, were always full of musical innovations. Pic/Wikimedia Commons

Richard Williams, senior lecturer in music and South Asian studies at the SOAS University of London, first got interested in Indian classical music when he visited Vrindavan a few years ago. “I met these priests and was collecting poetry from the 18th century, and then, they asked me to drop by in the evening. There was a ceremony where they sang these poems, and I realised that if I factored out music, I would be missing out on a lot,” recalls Williams.

The musical evening led him on a completely different journey. Later, while pursuing his PhD at King’s College, Dr Katherine Butler Schofield, a historian of music and listening in Mughal India and the paracolonial Indian Ocean, told him about the last king of Awadh, Mirza Wajid Ali Shah, and the time he moved to Calcutta. “She suggested I find out more about him, and then I did, and he was quite a character,” he says over a video call from London. His research has now taken shape as a book, The Scattered Court: Hindustani Music in Colonial Bengal (Chicago University Press), where Williams focuses on the creation of music post 1857, and the courts of Wajid Ali Shah.

Richard Williams

Richard Williams

The book explores the life of the “colourful king”, who was also a poet, lyricist and dancer, and his passion for all things musical, first in his court in Lucknow, and later in the suburbs of Calcutta, where he was exiled by the East India Company. It was a time when the Indian subcontinent was transitioning between the Mughal Empire and British Colonialism, and change was in the air, says Williams, and Wajid Ali Shah was at the centre of this new riff.

Excerpts from the interview.

You write about Wajid Ali Shah’s court travelling from Lucknow to Calcutta, at a time when the Mughal Empire gave way to British colonialism—what were the major musical changes that took place at the time?

After the revolt of 1857, people thought everything changed. Music was not meant for kings anymore, it was meant for the masses. It was not just about kathak and thumri, but about Hindu intellectuals and nationalist music. My book complicates that notion. Wajid Ali was a great patron, but he was also a poet, lyricist, dancer, choreographer and played the sitar and drums. What was really happening was that he was experimenting—he invited the street singers in his courts, and was also a fan of female dancers who did khemta, which was all about the movement of the hips. He was criticised for being too effeminate, but he was a trendsetter. He even developed musical theatre.

That sounds like an exciting time...

Yes, it was. Two other developments happened then. Gramophone recordings started, and that changed the aesthetics of music, and how it was performed. Many recording artistes had connections to his court. Also, the morality angle towards women in music was changing. They were no longer supposed to be only courtesans and prostitutes. In fact, reform campaigns to change that perception were on.

You also speak about his wife Alam Ara, who was better known as Khas Mahal, and how she affected the music of that time.

She was wonderful. She wrote lyrics, thumris, and the two collaborated on many compositions. In fact, she held hush hush music parties in her house. Women were not supposed to do music, but slowly, I am discovering that there were many more women musicians at the time.

Is that going to be the subject of another work?

Yes (laughs).

Now that the book is out, what do you hope it will lead to?

I am hoping it gets people excited about this period. I hope they want to know more. We need to stop relying on English literature of the time, and dwell into Urdu and Bengali research about the same. There is so much to find out.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!