Authentic is officially 2023’s Word of The Year, as raw and real is back in vogue in an age gripped by AI, deepfakes and social media pretence. We looked high and low, and put contenders through the truth test to find our Top 8

Jackie Shroff, Shibari Practitioner, History Professor, Health Influence, Startup Founder, Independent Journalist, Lingerie Model and Non-Binary SC Lawyer

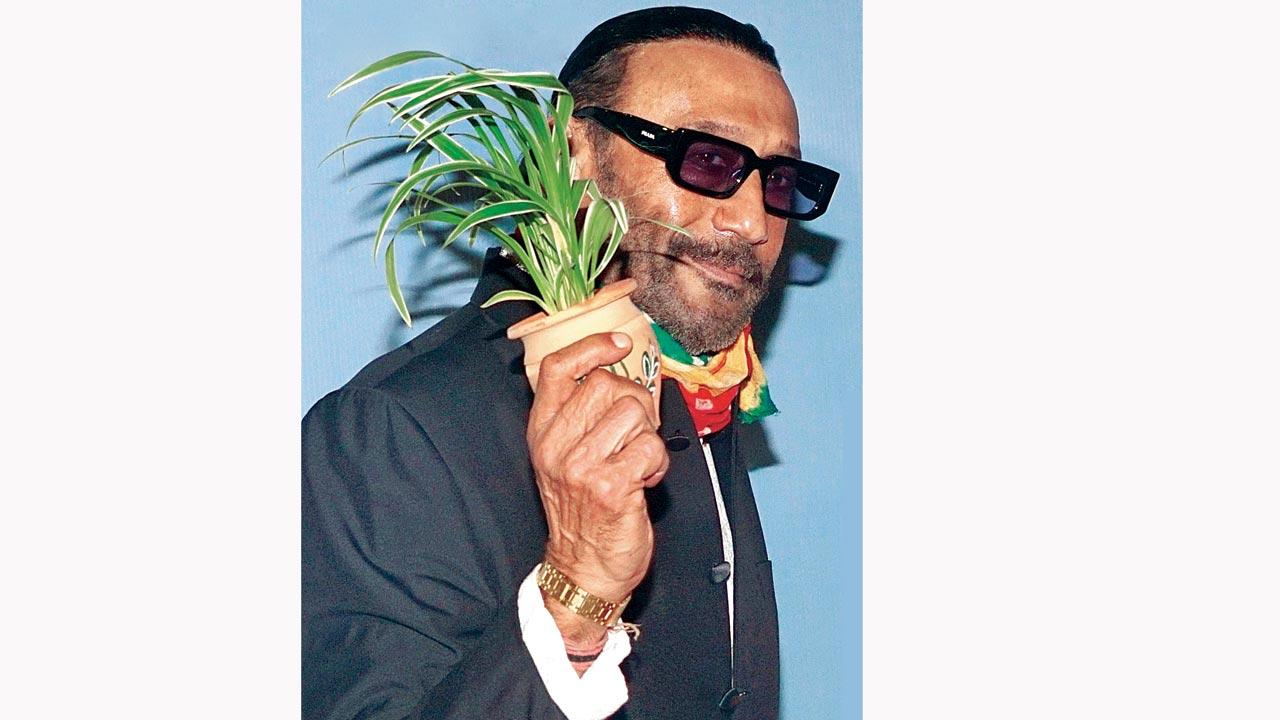

Unapologetically bhidu

ADVERTISEMENT

Why we love the veteran actor’s Instagram account that’s raw and real, brimming with greenery and 100 per cent Jaggu Dada

Jackie Shroff, Actor

Kal subu [subah] uth ke message karta hoon,” is how Jackie Shroff confirms an interview with this writer. Clearly, the veteran actor who stole ladies’ hearts back in the 1990s texts exactly the way he talks.

His handle is @apnabhidu, his Threads display name is pedlagaobhidu; ‘bhidu’ [friend], along with ‘bawa’ [brother] and ‘darling’ are used liberally all through

the interview.

Shroff got onto Instagram three years ago and has since, been using it to talk about the environment, why we should nurture and protect trees and the importance of staying fit. His posts carry photographs of him dressed in chic bandhgalas and happy shirts, with a sapling in hand; on some days, we see him mid-push-up. Every post, including the visuals and text, is 100 per cent Jaggu Dada.

We catch up with the star the next morning at 8.30 over a video call; this writer is sipping coffee to stir to life; he, at 66, is fresh as a daisy. He is sporting a Gandhi topi and dark glasses inside a room in his Bandra apartment.

“I’m not new to the Internet,” he clarifies. “I used to blog in 1994, but not many knew about it. I continued till 1997.” Does he have a social media strategy he follows? “Aisa kuch bhi nahin hai, bhidu! If I see something I like, if I notice someone’s hard work or something that needs to be talked about, I post. Sometimes, mera bachcha log tell me kya daal ne ka. Of course, I have a team to manage my social media but it’s not like they call the shots or I do,” he says.

Fitness and green living are clearly his passions. There’s a large plant in his bedroom that we catch a glimpse of. He urges us to have one in ours as well.

“We all exhale carbon dioxide all day. Even if my wife and I are saying, ‘I love you’ to each other, nikalta toh carbon dioxide hi hai. We need to ensure there is enough oxygen around us, especially because we are all so used to using air conditioners. We must breathe good air.”

With fitness, it’s clear that he gives more credence to pranayama (ancient breathing yoga technique) over vyayam or physical training. We could have tried to explain why; we prefer quoting him: “Pehle saans ko utha, phir wazan utha.”

What Shroff stays clear of posting is any content that could hurt religious sentiments. “The views don’t matter,” he argues. “I’m not concerned if 2,500 or 25,000 people see my post. I’m happy even if two-and-a-half do.” This approach is linked to his belief that social media must educate indiscriminately across divides.

“Take thalassemia, for instance. It is such a deadly disease. Babies as little as six months are forced to undergo blood transfusion. Is this not a serious issue [to discuss]? How many would-be parents undergo testing for thalassemia? It’s this that I wish to use my Instagram account to discuss,” he says, just as he is interrupted by a Persian cat who has got into a scrap with a pigeon. Shroff tries to break the fight. “Iska naam JD hai,” he says, pointing to the feline. “Bole toh, Jaggu Dada.”

He won’t be long here. Come New Year’s Eve, and Shroff is set to take off to his Talegaon farmhouse where he plans to ring in 2024 with close friends. “Chal, darling, milte hain baad mein,” he signs off.

Gautam S Mengle

gautam.mengle@mid-day.com

An honest cuppa

For the founders of a coffee company, openness and honesty are essential ingredients to building a product and community

Vardhman Jain, Coffee Startup Founder

At Bonomi, it isn’t just the cold brew—steeped lovingly for 18 hours and then expertly filtered—that is undiluted. As co-founder Vardhman Jain lets in a lay tea-drinker to the world of ready-to-drink coffee, he paints nuanced portraits of the two kind of users who exist: “Those who are serious and invest in a home brewing and grinding set-up, and those who drink it for energy, to break the lethargy first thing in the morning”. Jain and Armaan Reet, his partner, were certain they don’t want to compromise on the fundamentals, which they call the ‘first principles’: the flavours, the low acidity and the promise of a refreshing, low-calorie beverage.

The two friends met during their coinciding stints at Uber, crossing paths again when Jain joined Reet as a consultant for a former version of the business. Come February 2022, BONOMI was re-born as a coffee company—a long journey for Jain which began a decade ago, when he bought his first drip coffee maker. Through the years of evolving his taste palette and training as a barista on weekends, Jain now has a commitment to flavour. When BONOMI users praise the brand’s offerings on X, you’ll find Jain (@lightroastguy) openly admitting to the research and effort that made it all possible.

And they always have their ears to the ground. “From day 1, we were certain about making all our products in-house and not contract manufacturing like the other players in the market… Every new flavour or category we venture into, we make sure to send samples to our customers for feedback or invite them for a blind tasting to our brewery. If it doesn’t pass the customer test, we don’t launch it,” Jain asserts. It’s a brand philosophy driven by pride in the product, but also building customer trust.

Jain’s—and by extension, BONOMI’s—honesty manifests in the co-founder talking about the challenges of running a startup, as well as acknowledging when their products can be improved. “The advantage of a blind tasting is that we can go back to the drawing board and fix the recipe… For example, the last one revealed that our cold coffee requires a little work with respect to the thickness of the beverage,” he shares.

The payoffs they are rewarded with aren’t just repeat customers. Jain reveals that 70 per cent of their users funded the company’s seed round of funding. “We want to build it in the open and involve the community and users at every step of the process,” he says jubilantly.

Neerja Deodhar

neerja.deodhar@mid-day.com

Send me legal notice, I’ll get you publicly noticed

The poster child for the war against processed goodies, the Food Pharmer rips apart packaged foods one nutrition table at a time

Revant Himatsingka, Health Influencer

On the 1st of April, Revant Himatsingka became a household name, after he uploaded a video about a beloved health drink that made the entire nation

stop sipping.

The video talked about how the drink, long advertised as nutritious and essential for growth, contained unhealthy amounts of refined sugar. It also pointed out that this fact was inconspicuously mentioned in the nutrition table as ‘added sugar’ on the back of the packet.

It had only been a month since the Wharton graduate (MBA) had quit his high paying job in the US. He was in the middle of moving back to his hometown Kolkata, a decision, Himatsingka says, that scratched a longstanding itch to do something for the greater good.

The fateful day that spun the health-influencer’s world on its axis was April 13—the makers of the health drink issued a legal notice.

Though Himatsingka immediately pulled the video down, it continued to circulate through WhatsApp and can still be easily accessed as anonymous accounts reupload it in a gesture of solidarity. “I got around four legal notices from different brands but the health drink one was the first and also the one that made headlines,” says the 31-year-old over the phone from the land of Tagore and trams. “Not only was I unemployed, but overnight, I had multiple legal notices to deal with. You can only imagine my state of mind.”

In the weeks that followed, Himatsingka’s social media handles fell silent, and eventually, after two weeks, a subdued post about misleading nutritional values in processed food popped up. “I didn’t name any brands,” he says, “just used words such as refined oil, refined sugar and left it at that.” He was flooded with DMs. “I got many comments and messages saying I mustn’t be deterred by legal notices. Some confessed that they never knew what was in the packaged food or beverage they consumed, until they saw my video,” he says, recalling the turning point.

Soon, Himatsingka was naming and shaming again, but the following videos were more urgent. He terms it positive aggression, and even has that printed on T-shirts.

“I was bullied as a child,” says the voice of health-conscious India, “and after what I had been through this year, I decided that I will not tolerate it anymore. I thought to myself, I will not be scared of them; they should be scared of me and the public. My new mantra is, if you send me a legal notice, I will get you publicly noticed.”

Last week, the makers of the infamous health drink announced a 15 per cent reduction in sugar content in their product. “This is a quintessential example of what a nutrition-educated society can do,” he says.

Addressing haters, he says, “Everyone thinks I make these videos to get noticed, but I am also working with health experts to help with adding nutrition to the curriculum in private schools. I also collaborate with government agencies to formulate long term policies about guidelines for the packaged food industry.”

The upheaval of the last eight months has expanded Himatsingka’s work in a way he couldn’t envision when he moved back to India. “My focus for 2024 will be what can I do for 140 crore Indians in the long run,” he says with admirable resolution, “I am not working for those who are health conscious but for those children, teenagers, parents, and adults who are not. I can almost see them before my eyes, skipping from Reel to Reel. I want them to pause when I pop up on their device; I want them to be empowered.”

Himatsingka’s immediate work is to get companies to print the nutritional value table on the front of the packages, instead of the back. Making the health hazards impossible for you, the next time you take a spoonful, to miss.

Arpika Bhosale

arpika.bhosale@mid-day.com

Roped in by desire

A creative professional uses Shibari Japanese decorative bondage and their Instagram account to speak about the healing, meditative potential of bondage and kink

Amiya, Shibari Practitioner

Knots, tied with a delicate touch and in intricate combinations, are the defining feature of Amiya’s Shibari practice. In posts and Reels where their hands nimbly turn rope into an artistic medium, they make the Japanese form of erotic bondage look effortless. An unabashed dominatrix, Amiya is one of the few Indian faces of this advanced kink practice—a rare femme one pursuing it professionally and building a community around it.

The 26-year-old, who is also a tattoo artist and creative director, tells mid-day that they were always fascinated by Japanese culture. “I was drawn by Shibari specifically because of its aesthetic value and the fact that it didn’t resemble dungeon bondage.”

Silly Hands—Amiya’s six-month-old Shibari venture—and its Instagram page (@sillyhands.shibari) features visuals of rope in communication with skin; the participants’ bodies and faces have an almost meditative look about them. Their workshops and classes aren’t sexual but sensual, akin to a physical activity like yoga, which helps people connect to their bodies and emotions.

“Shibari invites you to connect with those parts of yourself that are unexplored or that you haven’t been in touch with for a while. There’s a lot of power in creating such spaces for others. It is a way to explore bondage in a safer, toned down manner rather than what we see in mainstream media, which, in my opinion, is very intimidating,” Amiya explains.

They invest much thought in how this form of bondage, in its nascent stages in India, will be received by people. The softness evoked in the posters and promotional photographs, too, is a conscious choice. “I really like working with female and femme photographers who have a female gaze,” says Amiya, who has engaged in this kink for over a year. The result is a sense of curiosity.

“Women approach me because Silly Hands is a way for them to experience Shibari with a queer, non-binary person like myself. In kink and BDSM spaces, men hold a great deal of power—power that doesn’t necessarily feel safe. I don’t feel seen or welcomed in such spaces,” they confess. It’s no surprise then that women have sought Amiya out to have conversations that they cannot openly have with others, perhaps not even their own partners.

With them, you can be assured that a pair of scissors will be kept at the ready to snip the ropes and safe words will be discussed beforehand. To them, consent, safety and communication are top priorities. “Even in the workshops and classes I offer to beginners, there’s a module at the start that focuses on these aspects [safety and consent]. Consent can be very different in kink spaces—there are things that you can and cannot do; and even the things you can do are accompanied by risk that both parties should be aware of,” they explain.

That these grey areas remain undiscussed in kink spaces, where there is often a power equation at play, has much to do with sex education in India—often flawed or compromised, and largely centred on normative, heterosexual pleasure. This is a subject that Amiya often raises on their account. “Comfort can only be achieved in environments where the other person is able to listen to you and read your bodily cues. When it comes to consent, I think if and who we are learning from matters a great deal,” Amiya notes.

They speak about their own perception with grace and confidence. “I’m a very open person even when it comes to the more personal aspects of my life. People can always get to know me, to recognise that I am more than just one aspect of myself.”

Neerja Deodhar

neerja.deodhar@mid-day.com

Jo dar gaya woh mar gaya

After bidding goodbye to mainstream news media, a journalist re-finds his voice and following, this time on YouTube

Sohit Mishra, Independent Journalist

In early September, the Mumbai journalist fraternity was murmuring about Sohit Mishra getting too brave for his own good. The bureau chief of a leading news channel had quit his job, reportedly over ethical differences with his employers and editors.

Before handing in his resignation, Mishra consulted his family—wife, parents, in-laws and his closest friends. The longest any of them took to understand why he was hanging up his boots was one minute. “They understood. I am blessed,” he tells mid-day.

The same month, Mishra, 30, uploaded a video on his YouTube, Sohit Mishra Official, titled Alvida Laal Mike. It was an explainer about why he had put in his papers. It garnered over two million likes.

Since then, Mishra has been using the free video-sharing platform to report on news and issues on his own terms, unfettered, and not restricted by the three-minute slot allotted to hacks on news channels. “The widely held opinion is that people don’t have the attention span to sit through long videos. That’s untrue. I can say this from first-hand experience,” says Mishra. “People ‘like’ and ‘follow’ and comment on videos that are as long as an hour. Those who are curious about what is truly going on will make the time and watch my segment end-to-end.”

The subjects of his reportage range from what to expect at Mumbai’s refurbished Byculla zoo to why tribal women living on the fringes of Kalyan scale a hill to fetch a pail of water from a waterfall. “When I published the Kalyan story, state officials got in touch with me to inquire about the exact location of the village. Soon, water was made available to the community. These are the stories I want to tell,” he says.

The response has been heartening and he didn’t quite expect it. “Shuruat mein main bahut darr gaya tha! [I was terrified in the beginning] I was not sure if the YouTube channel would work; my experience on X [formerly Twitter] had been toxic. But I was pleasantly surprised. The comments are often constructive. I have had viewers tell me that I need to stop focusing on politics and visit their city or village and highlight a social issue that they are grappling with. Some give me leads that I pursue as stories; I am grateful for the community I have been able to build.”

Mishra’s channel has gathered over two lakh subscribers in four months and at the heart of this number is a journalist keen to do his job well.

“We have to stand up for ourselves,” he says. “Take that step that you may be hesitating to take. Go with your heart.”

Arpika Bhosale

arpika.bhosale@mid-day.com

Brushing up facts

This scholar wipes propaganda off history’s face

Dr Ruchika Sharma, History professor

One of Dr Ruchika Sharma’s favourite videos on her own channel is titled Nalanda Ke Teen Jhooth or Three Myths of Nalanda. It busts the three popular myths associated with the ancient Buddhist monastery in modern day Bihar, such as its destruction by Bakthiyar Khilji, its burning down by the Turks and its sudden collapse.

Sharma’s detailed academic references set her YouTube channel, Eyeshadow and Etihas, apart. The Nalanda video alone has 13 references listed in the description. And instead of a pen or a laser pointer, she’s holding a make-up brush. Dr Sharma applies eyeshadow, lipstick and other forms of cosmetics while delivering hard facts.

“I was born and brought up Mehrauli,” she tells mid-day, “Both sets of my grandparents are from Punjab in Pakistan. They were refugees and a huge part of my childhood and teenage years were spent listening to stories that my dadi told me about Punjab before the Partition.”

Her first brush with history was in Class VIII, when her teacher said something that Sharma would always carry with her like a talisman: History cannot be taught from just one textbook. It changed her outlook towards the subject; till then, her idea of studying was underlining sentences in a textbook.

Sharma went on to major in Marketing and even got a job with a private firm, but history kept calling. In three months, she quit and enrolled for an MA in the subject at the Jawaharlal Nehru University. She majored in Medieval Indian History, and now teaches at the IP College in Delhi.

When it came to her YouTube channel, though, eyeshadow happened before etihas. “The pandemic was a pretty dark time in my life,” she reminisces. “I was in therapy and found [applying] eyeshadow very cathartic. I began learning how to do it through YouTube. I remember walking into class after the pandemic and my students telling me I should put up a tutorial. I demurred, saying I wasn’t that much of an expert. A student suggested I talk about history while applying it on.”

Today, her channel has 201 videos and 10.9k subscribers. “It’s fine if you make mistakes about history, but I think what’s sad is the propaganda,” she asserts, “because a lot of these myths tend to become very dangerous. For example, this idea that our community or our religion has treated women much better than yours. I mean, all religious communities have dehumanised women to a major extent.”

She didn’t start off as a myth buster; she was just putting out academic content. But of course, it attracted much hate, most of it from nameless, faceless trolls on Twitter and Instagram.

“YouTube is okay because you can let the comments lie,” she says. “Twitter, on the other hand, is a virtual lynch mob that will leave no stone unturned. But their basic aim is to get you to stop what you’re doing. So, every time I see comments about my neckline, my academic qualifications, I know that it is to silence me. It just goes to show that my work is causing an effect and these myths are getting dented if not busted.”

Gautam S Mengle

gautam.mengle@mid-day.com

Petition to slay

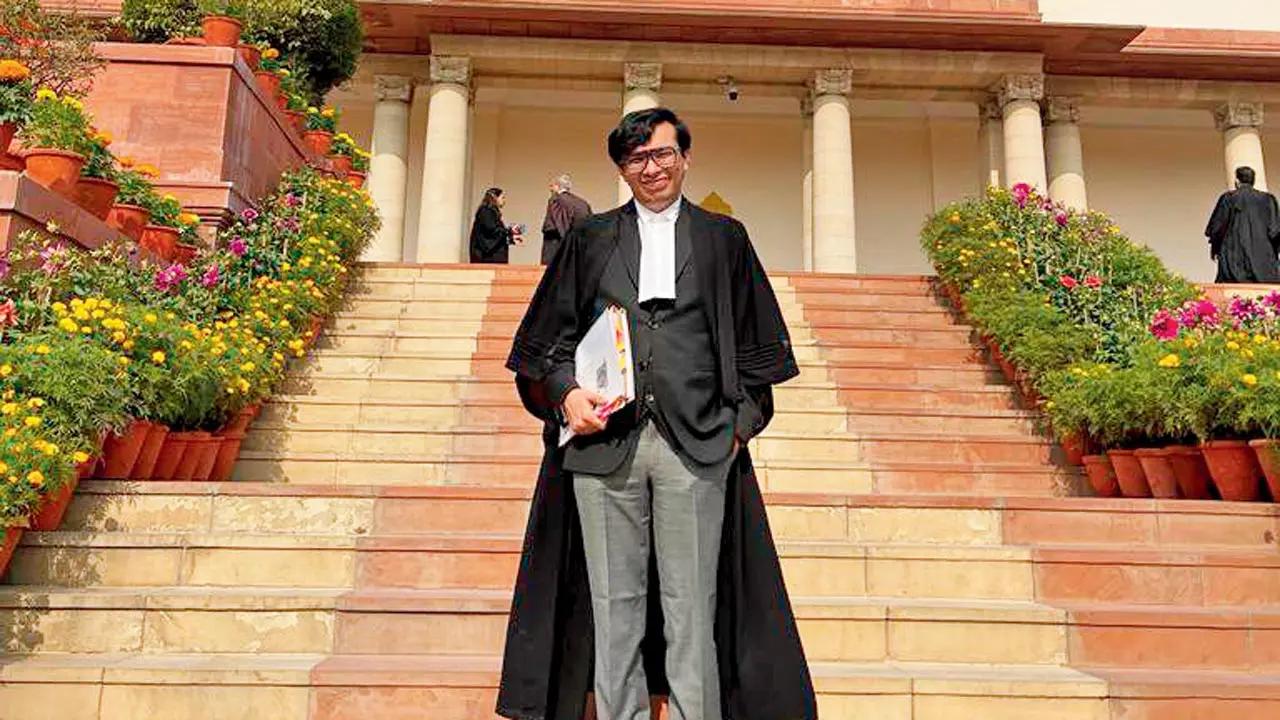

At the Supreme Court and on Instagram, this lawyer, queer activist and bioethicist leaves a mark

Rohin Bhatt, Supreme Court Lawyer

At the premises of the Supreme Court and in Delhi’s busy streets, Rohin Bhatt stands out with his pride socks and ties—fitting accessories to his advocate’s robes. The Ahmedabad-born lawyer may be all of 25, but the impact of his work is already being felt: In 2022, he wrote a letter to the Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, seeking interventions in the legal system to improve the experiences of queer lawyers. Five months later, the SC took its first steps towards the creation of nine universal restrooms and making its online appearance portal gender-neutral.

Bhatt, who works with senior advocate Indira Jaisingh, thinks of his social media accounts as diaries. To his followers, they’re a look into the human rights lawyer he wants to become, and the person he is. A collage of photo booth pictures taken with his partner—an unabashed expression of queer joy—is accompanied by an equally moving caption: “What are we in court for, if not to fundamentally love, be loved and be queer?”

It was posted on the day when hearings in the marriage equality case were about to begin. “These are the things the community has always been in court for—to have the full rights to love and not be discriminated against,” Bhatt tells mid-day. In a hazy but special screenshot, he can be seen assisting a senior advocate in the monumental case—a small role has transformed the very way in which he now sees the law. Bhatt wrote on Instagram that this moment had arrived two years after he came out; in this context, he was both lawyer and litigant.

The young advocate felt let down by the eventual outcome, but the experience challenged the training he received as a law student. “Working on the case as a queer person—as someone who has always been on the sidelines, watching the fight—and getting my hands dirty was not just an enlightening experience of what it means to do a case where your personal stakes are involved, but also one of the most influential cases I’ll do in my entire career,” he says, asserting that the fight is far from over.

In the manner of many millennials and Gen-Zs, Bhatt admits that some of his posts may be made consciously, but more often than not, he isn’t policing himself. It was in a joint decision that he and his partner determined that they would share pictures of each other publicly. “Once the decision is made, you have to live with the consequences. I’m in the public eye, whether I like it or not, but he didn’t get to make that call for himself. Oftentimes, when I get trolled or threatened, he gets trolled and threatened too,” the lawyer rues about his partner.

But Bhatt, like countless queer individuals in India, says he is no stranger to hate online. His letter to the CJI, which requested an additional column in application slips to mention people’s pronouns, led to waves of trolling. “Bullies hardly scare me. I don’t open those messages and they eventually get deleted,” he declares. Yet it is tough to be immune to fear when troll accounts have responded to his posts with his mother’s name—a detail he has never declared in public—or his home address.

Some days, Bhatt opens up on social media about his struggles with depression and overcoming them. Well-wishers in the legal industry and outside it tell him he needs to maintain a certain impression of seriousness. But the lawyer has always been predisposed to ignoring well-wishers. “Students have written to me after these posts, telling me that they thought their mental health issues may hold them back from becoming lawyers. These are conversations that don’t take place in my industry, but thankfully, things are now changing. The hope is that I can reach out to more people like these students,” Bhatt says.

Neerja Deodhar

neerja.deodhar@mid-day.com

Starting the right conversations

A 52-year-old model is using her Instagram to question why the profession should be limited by age

Geeta J, Model

Say the words lingerie model, and a certain picture emerges: And this picture will automatically decide the age of the model. The visualisation will not extend beyond this age group.

Geeta J, a Thane resident, is 52 years old and a lingerie model. And now, through her Instagram account—just_geet—she is asking why there should be an age limit to this profession.

Geeta was 50 when she won the first runner-up position in a beauty pageant and a finalist position in another. Before this, she worked as a pre-primary school teacher. Her achievements led to modelling assignments, and also a reality check.

“I was fit, confident, full of enthusiasm, and ready to take on challenges,” she says, “One of the entities that approached me was a lingerie label. Everything was going smoothly till they learned how old I was. After that, the conversation changed. They said they’d start production of lingerie ‘suitable to my age’ and get back to me.”

Geeta had two choices, stay silent or do something about it. “I did some research and observed that most lingerie brands feature younger models in commercials,” says the now full-time model. “I felt that a message was being sent out, even if unconsciously, that people don’t use certain products after they cross a certain age. I have yet to see a model over 40 years of age in lingerie commercials.”

Geeta started a campaign on change.org and set up a dedicated Instagram account to talk about ageism. She also did a photoshoot sporting lingerie and posted the pictures on Instagram.

“It is the digital age and advertisements pop up all over the Internet to influence shopping habits,” says Geeta. “They also have the power to change the perspectives of customers. It is still not common to see women my age in lingerie, workout gear, or trendy apparel, all of which I post regularly.”

The response has been a mix of encouragement and disparagement, but Geeta is happy to have at least started a conversation. She is also aware that social media is a numbers game and that she needs to keep posting, no matter how much hate she gets. Her focus, though, is her passion.

“Obsessing over metrics and numbers feels like I’m in a rat race,” she says, “where I don’t have freedom or control over my work. Negative comments don’t affect me much now, but if, for any reason, I don’t feel like posting or need a break, I take one. Our best work and inspiration comes from being well-rested and rejuvenated. That is when new and creative ideas truly blossom.”

Gautam S Mengle

gautam.mengle@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!