mid-day spends a morning with six students painstakingly preserving specimens of indigenous or extinct fauna, as they learn to turn this into their specialised skill

A student, who is part of the three-month course on preservation of natural history specimens at CSMVS, cleans tiger skin that was donated by the Maharani of Dhar in 1922. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

In one corner, a man in a lab coat is bent over a 10 foot-long tiger skin, concentrating on cleaning a 2-inch by 2-inch patch with slow strokes of a cotton earbud. Behind us, another man is using a dentist’s ultrasonic scaler—usually reserved for chipping away at tartar—on the skull of an Indian bison. It’s the last room reached by the colonnade in the left wing of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralay (CSMVS).

In the open corridor outside, Ravi Chafe, senior technician, Natural History, CSMVS, is concentrating on what looks like a deflated mucous balloon, splayed and stretched over what could be an overturned kadhai. There’s a sour stink in the air. That is the ocean sunfish—found in such depths that it is too dark to care about looks, and it’s only one of the two specimens found in Maharashtra. The other one is stuffed and part of a diorama in the natural history wing of the museum.

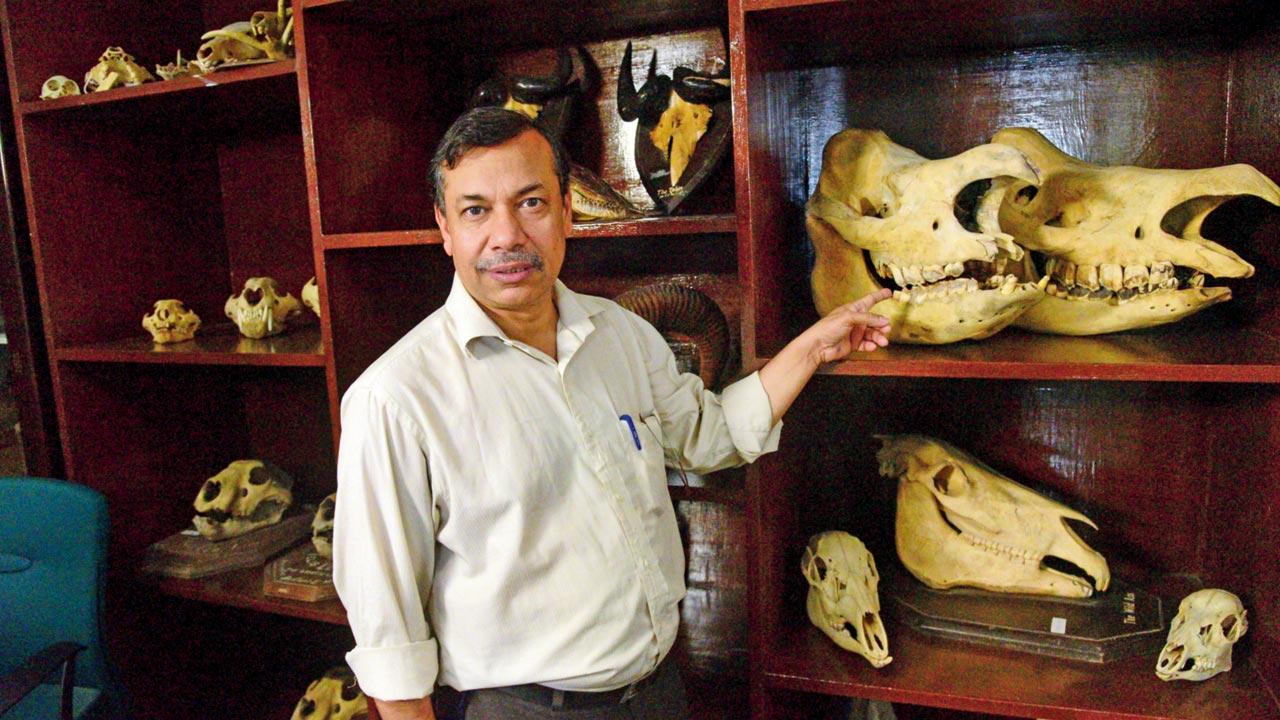

Dr KA Raheem

Dr KA Raheem

The tiger skin is more than 100 years old, and a prized possession. It was donated by the Maharani of Dhar in 1922. Its tail is detached and on the side. Up until a few months ago, it was mounted on a wooden frame on the wall behind the man devoted to it now. There are bald patches and after about a month-and-a-half of intense attention to restore it, it will go into a glass case.

The six students working here are part of the three-month pioneering course—conducted by Tata Trusts and CSMVS Museum in technical partnership with National Museum of Natural History—on preservation of natural history specimens. After the course, they will undergo a month-long internship before going out into a country that currently has no job sector for this particular skill. It’s ironic that a nation that draws so much tourism and international equity for culture and heritage, has very few skilled preservation technicians.

Anupam Sah, academic consultant, Tata Trusts Art Conservation Initiative, consulting head, Art Conservation, CSMVS

Anupam Sah, academic consultant, Tata Trusts Art Conservation Initiative, consulting head, Art Conservation, CSMVS

Dr KA Raheem, chairman of the Department of Museology at Aligarh Muslim University, who is leading the course, estimates that the state would have 10 to 15 preservation technicians, and the pan India number would be under 50. Yet every state museum has a natural history wing, as well as dedicated museums.

“The past few years have been great for conservation,” says Anupam Sah, the academic consultant for the Tata Trusts Art Conservation Initiative and consulting head of Art Conservation at CSMVS. “People have become alert about conserving heritage and culture at the personal, as well as the community level. What we are trying to do is not just equip students to be skilled personnel, but inculcate critical thinking capabilities that will make them decision makers.”

Dr KA Raheem says these can also provide DNA samples to resurrect extinct species

Dr KA Raheem says these can also provide DNA samples to resurrect extinct species

The course culminates in a presentation by each of the six students (chosen out of 66 applicants) about preservation of an assigned specimen. “Once the students present their chosen method and materials, they have to defend their choices and make a case for why these are better than others,” says Sah.

Great contemplation has been made on every aspect of the course—the curriculum, process, faculty, application, future scope and cross pollinations. This is one of 10 courses that the Tata Trusts is conducting in five institutions across India; CSMVS is the partner for Western India. Each is dedicated to preservation of one medium: Metal, stone, terracotta, etc. This one concentrates on organic material. Apart from conservation and restoration techniques, it covers health & safety and disposal of materials. The teaching faculty involves 16 specialists, from across India and abroad, covering even peripheral—but crucial—aspects such as Integrated Pest Management (by Bill Landsberger of the National Museum in Berlin) and also of attached domain specialists, who would know the behaviour of natural and synthetic materials used for mounting the organic specimen.

Students work on specimens housed at CSMVS

Students work on specimens housed at CSMVS

“We chose applicants who were already working in the field and came with a zoological or preservation background, so that we could build further on existing capacity,” says Sah. “In many earlier courses, directors of museums and collections, curators, historians had enrolled, but we found there was little trickle-down effect. They were not conservators who would work on specimens, nor were they able to impart the learning to their junior colleagues,” says Deepika Sorabjee.

“After the course is over,” interjects Deepika Sorabjee, who heads Arts and Culture at Tata Trusts, “We will list the students on our websites so that museums and private collectors can contact them. We are also trying to professionalise the sector, increase conservation opportunities to be engaged with by institutions, government, and the private sector by demonstrating modules that can be carried on by the institutions.”

“Scientists of the Western world were much interested in preserving and studying natural history specimens. Trained by the British, Indian taxidermists who worked with them died out and the skill was not passed on,” explains Sah. A Jesuit headmaster’s collection of stuffed birds at nearby Campion School is testimony to the fact, says Sorabjee.

The result is that preservation of existing specimens relies on dated information, such as the use of corrosive chemicals that may protect a hide from environmental damage, but not from itself. There has also been no sharing of methodologies among peer museums and individuals.

One of the things Raheem, who leads the course is concentrating on, is testing benign and traditional agents of preservation. “Even something as simple as storing our clothes with naphthalene balls,” he says, “now we are finding out that it can cause skin diseases. So, we are testing simple indigenous agents such as cinnamon, cloves, cardamoms slipped into the muslin cloth that fabrics would be wrapped in for storage. These not only kept away pests and moths, the clothes smelled better, too. We are going to see how all varieties of agents—chemical and natural—can be used.” The ultrasonic ablator (dentist’s scaler) is one such packet of lateral thinking applied by conservation professionals.

Raheem believes that preservation not only links us to the past, but can also seed the future: Specimens are sources of viable DNA sample. A PhD student under him is working on a thesis where by relating the DNA of the recently flown-in African cheetahs to the DNA of the extinct Indian cheetah (procured from a specimen), we could resurrect the species through cloning.

It could be the future of the extinct two-horned (Woolly) Sumatran Rhinoceros, once found in the lower reaches of the Himalayas, whose skull is on the second shelf near the door, next to the normal variety of its species, which is also endangered. The stuffed shekhru (Indian Giant Squirrel) encased in glass outside, in a diorama of other native squirrels, could also shed some DNA for its own future revival. No one is sure when it went extinct and biologists hesitate even to label it such, lest a specimen pop up somewhere, says Manoj Chaudhari, one of the technicians understudy and also the assistant curator, Natural History Collections, CSMVS.

Extinct or not, this is also the only way generations will be able to see these animals up close, points out Sah. In the Natural History wing, flocks of hip-high students from St Mary’s School in Andheri are drawn to the stuffed rhinoceros (whose skin is disintegrating and will receive special attention soon) and the gaur cow and calf. They enter in a single file under the arch of the lower jaw bone of a whale, and the air fills with their chirping.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!