An American architect for whom Mumbai is home dips into old archives and studios over seven years to tell the story of an audaciously imagined city before it became a thriving megalopolis

After hearing about William Sowerby’s drainage plan of 1868 for the overflowing metropolis, Executive Engineer Hector Tulloch is said to have “held up his hands in horror at the idea of a canal passing through the heart of Bombay”

When Gerald Aungier took over as governor of Bombay in 1669, a mammoth task awaited him. A message from his bosses in Britain relayed a simple instruction: Build a new city here (and soon). A map of London was also sent to fuel his inspiration. Aungier, however, had resisted the idea. Though aware of the inevitability of his role in transforming this land of marshes and disease into one of Britain’s richest commercial hub, he had written back saying that the “timing wasn’t right”. “In order to build such a city, he’d have to first cut down hundreds of palms, but the local populace was deeply attached to their trees. He conveyed to the authorities that if he acted immediately, there could be riots and unrest. Instead, he focused on strengthening the Bombay castle,” says Robert Stephens, principal, RMA Architects and founder of Urbs Indis, a studio that narrates lesser-known civic histories through juxtaposition of archival material with contemporary aerial photographs of urban India. That’s how “Bombay” became the first unrealised project in the city’s history, Stephens tells us over a video call.

ADVERTISEMENT

The architect has re-envisioned this particular project in a soon-to-release self-published coffee table title, Bombay Imagined: An Illustrated History of the Unbuilt City. Armed with just this tiny piece of information available in official records, Stephens speculates how the Fort precinct would have looked had Aungier acted on the instruction right then. In the artwork that finds its way into the book, the Bombay Castle—modelled on archival drawings that he had access to—stands on the fringes of the island surrounded by a grove of palms, facing the vast blue Arabian Sea. Far ahead is a green hillock—what we today know as Malabar Hill—with the salt flats to the right. The image shows a precinct that has been completely eroded of its palm trees, enough to incite locals, who’ve gheraoed the castle’s walls. None of this happened for real of course, but Stephens’ work explores the “what ifs” rather than the “what was”.

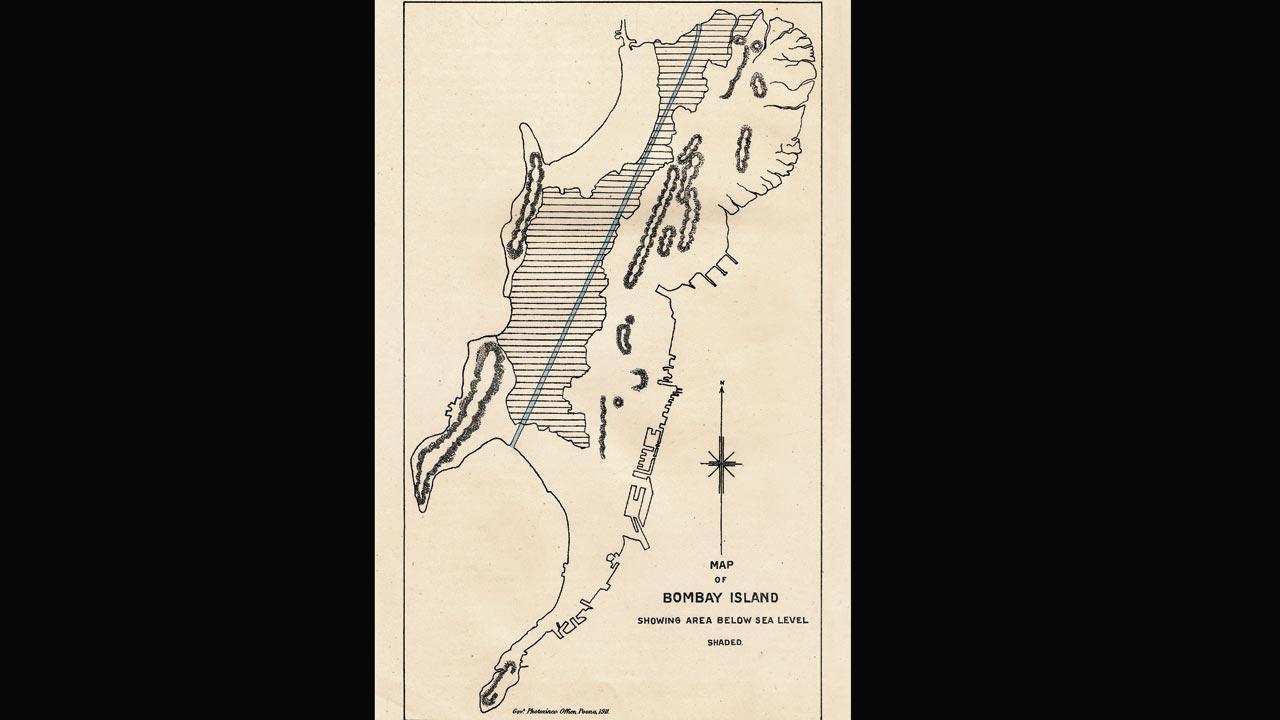

Image Courtesy/Urbs Indis Library and Fauwaz Khan (overlay). Sowerby’s proposed canal is shown in blue

Image Courtesy/Urbs Indis Library and Fauwaz Khan (overlay). Sowerby’s proposed canal is shown in blue

The result of seven years of exhaustive research that involved scouring nearly five dozen archives, libraries and studios, and collaborations with various visual artists and architects, his new book documents 200 unfulfilled urban visions for the city, spanning nearly four centuries.

The book is a product of chance, says Stephens, who is a passionate collector of rare and second-hand books on the city. Back in 2014, he stumbled upon a publication that he procured from a London bookseller titled, Professional Papers on Indian Engineering (1869). “While casually browsing through it, I came across a scheme for the drainage of Bombay by Hector Tulloch. In it, Tulloch had given a footnote about how there should be a park at Mahalaxmi, but that he couldn’t take credit for the idea, as it was the vision of Arthur Crawford [Bombay’s first municipal commissioner and collector of Bombay]. I then tracked that reference down and found a book by Crawford at the Asiatic Library called The Development of New Bombay,” says Stephens. Two pages from that book spoke of this plan for a 400-acre people’s park at Mahalaxmi. “It was fascinating, because today, the racecourse is very much part of our reality, but it’s out of bounds in many ways. Crawford, on the other hand, imagined this space could become the heart of the city for all residents to recreate and have fun… that project sparked something inside me. I wondered what else could be out there that people had dreamed up for Bombay but had gone unrealised.”

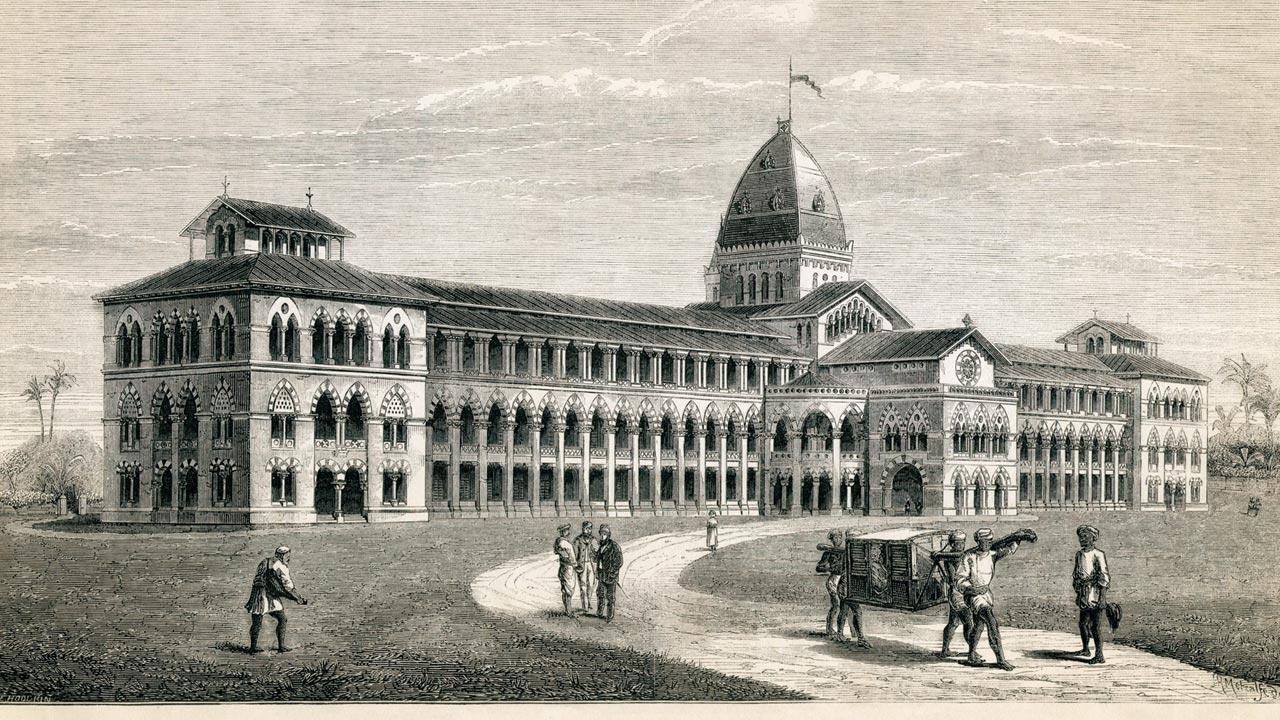

Thomas Roger Smith’s proposed European General Hospital of 1863, which was to replace healthcare facilities described at the time as “a disgraceful reflection on the humanity of the Government and the European community in Bombay”. Image Courtesy/Urbs Indis Library

Stephens research and architectural practice led him to a string of projects and proposals that straddle the audacious, the bold and even the outrageous. “Sometimes these project ideas were just two or three lines long, and others were verbose documents and reports. But, at the core, all of them hoped to transform or develop the city, if not improve. The book picks up on this wide range,” he shares.

Thirty one active studios from across the world have contributed content to this book, including Apostrophe A+uD, Bandra Collective, DCOOP, Foster + Partners, Ganti & Associates, Heatherwick Studio, HKS, IMK Architects, Jakob + MacFarlane, Mad(e) in Mumbai, MO-OF, Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos, OMA, PK Das & Associates, Ratan J Batliboi Consultants, among many others. Stephens approached them after researching specific unbuilt projects of theirs that had caught his attention.

Robert Stephens

Robert Stephens

While most of the proposals submitted by these firms were thorough to the tee, Stephens had to re-imagine the designs for ideas that were either never visually conceived or for which content had not survived. He brainstormed on the speculative art with Aniket Umaria (Mumbai), Akhil Alukkaran (Calicut), Yannis Efstathiou (Berlin) and Lambros Papathanasiou (Athens) who breathed new life into 30 of these projects. The Bombay that Aungier didn’t build was one such.

Among the more radical ideas was the Bombay Municipal Corporation’s proposal to fill the Banganga Tank and transform the sacred waterbody into a children’s park in 1949—a project that this writer is grateful didn’t work out. In their speculation Stephen’s team reimagines the reclaimed tank as a cricket pitch; the only vestiges of its former glory are the centuries-old temples that surround it, and the ancient stone steps.

The Bombay Municipal Corporation’s proposal to fill Banganga Tank and transform the sacred waterbody into a children’s park in 1949. Image Courtesy/Speculation by Aniket Umaria

The Bombay Municipal Corporation’s proposal to fill Banganga Tank and transform the sacred waterbody into a children’s park in 1949. Image Courtesy/Speculation by Aniket Umaria

There were also projects like the Elephanta tavern and ballroom, where he deliberately chose not to include speculative art—perhaps, because of its sacrilegious nature. “The proposal from 1850 was intended to transform the caves into a tavern and ballroom. But, the context [for the initiative] is important here. Around that time in Bombay, several [anti-alcohol] activists were trying to make Sunday a ‘dry day’. But Sunday also corresponded with the one day that sailors had an off. So, in a smart move, someone [unknown] proposed to start a tavern for sailors at Elephanta, as it was outside the city’s jurisdiction.” In the book, he has supplemented the description of this proposal with an original painting of the cave from 1865 by Rienzi Walton. “It didn’t feel right to visualise this project. I thought let’s just give readers an arresting image from that time, and have them overlay their imagination.”

Apart from speculative art, the book has extensively researched relief maps, created by architects Rimshi Agrawal and Kshitij Mahashabde, which accompany and locate each unrealised project within the city’s greater geographic context.

The Bombay Imagined team. (From left) Aniket Umaria (speculation art), Deshna Mehta and Carol Nair of Studio Anugraha (book design), Fauwaz Khan (project management and overlays) and Robert Stephens (research and writing). Pic/Tina Nandi

The Bombay Imagined team. (From left) Aniket Umaria (speculation art), Deshna Mehta and Carol Nair of Studio Anugraha (book design), Fauwaz Khan (project management and overlays) and Robert Stephens (research and writing). Pic/Tina Nandi

Eighteen of the documented projects also feature overlays—propositions drawn to scale over original archival material—by architect Fauwaz Khan. The base images for some of the selected overlays feature Stephens’ aerial photographs of Mumbai, captured over the last decade and taken from 5,000 to 10,000 ft above sea level. An example is the 15-km-long proposal for the Worli-Nariman Point Sea Link by the Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation in 1999. The image in the book overlays a sea link in purple, on a black and white aerial photograph of the city. “This is to indicate where the new intervention has been made,” he says. “Civic and environmental activists had fought tooth and nail against the MSRDC’s plan to encircle South Mumbai with an elevated highway in the Arabian Sea,” writes Stephens in the book. Over two decades later, it has been replaced by the Coastal Road project.

According to Stephens, one of the more impressive designs for the city came from Pheroze Kudianavala, the architect behind the Reserve Bank of India tower in Fort and the World Trade Centre in Cuffe Parade. Kudianavala, who now lives in Dubai, and is in his 90s, had shared his original designs and material with Stephens. He had envisioned creating a 102-storey tower in Cuffe Parade in 1969. The skyscrapers being planned in Bombay of the 1960s ranged from eight to 23 storeys. “That was the limit then, but Kudianavala’s vision was radical, in response to an ambitious client from Kenya who asked for a 102-storey tower. He travelled the world for this project, and even met the famed English engineer Ove Arup in London. He really set the wheels in motion for the project outside of India. Unfortunately, when he returned, he learnt that while he was away, the land had been sold to someone else!”

Architect Hafeez Contractor’s Eastern Waterfront proposal of 2014. Sixteen years earlier, Contractor speculated, “All future development must necessarily be vertical.” Image Courtesy/Architect Hafeez

Architect Hafeez Contractor’s Eastern Waterfront proposal of 2014. Sixteen years earlier, Contractor speculated, “All future development must necessarily be vertical.” Image Courtesy/Architect Hafeez

There’s also English educator and architect Claude Batley’s Collective Living Superstructure, which Stephens says reimagined utilising existing urban space for the common good. Batley shared his vision for the project, which drew inspiration from architect-designer-writer Wells Coates’ Isokon Flats at Hampstead (1934), at a Rotary Club luncheon in November 1936. “He envisioned from [present-day] Eros [cinema] to the full length of Oval Maidan, a massive superstructure with hundreds of housing units. It had homes for a range of classes, with two or three-bedroom units. His argument was that Bombay’s housing should respond to its need, which is that it should not be restricted to the elite, and the building along the Oval should speak to the grandeur of the High Court and the Secretariat that were on the opposite side. So, Batley was thinking at the micro unit of the individual as well the urban scale,” says Stephens.

Eventually, these plots got chopped up into smaller units, receiving a thumbs down from Batley, who described them as “little boarding houses”. “Today, of course, these residential buildings [around the Fort, Churchgate and Marine Drive area, part of the Victoria Gothic and Art Deco ensemble] have been included in the UNSECO World Heritage Site list. But, at the time, the leading architect of Bombay thought that this was a terrible moment for the city, because one of its most valued façades was being made available only to the elite. I find this fascinating, because when we see it now, it’s actually a critique on the city by someone whom we celebrate. It’s also ironic, because today we are celebrating what he was critiquing then.”

Despite the meticulous research that has gone into this work, Stephens insists that his pursuit wasn’t academic. “I love finding stories and telling them in a way that’s easy to understand and enjoyable. Each story nestles the salient features of the project within the context of the city at that time. For me it was a way of discovering new aspects of Bombay, which one wouldn’t otherwise seek out.” He mentions how Deshna Mehta, the co-founder of Mumbai-based design firm Studio Anugraha, who helmed the book design with Carol Nair, described his work as a “museum”. “I quite agreed with that. It’s a space to enjoy captivating imagery of a city that could have been.”

1850

The year a proposal was made to turn Elephanta into a tavern

To pre-order a copy The book, which goes in for printing in February, will release in March, and is currently available for pre-orders. www.urbsindis.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!