Sunday mid-day goes on a walk around Panvel with Professor Smita Dalvi, who’s in a race against urbanisation to preserve the pit-stop town’s historical buildings

As with all six lakes in the city, Vishrale or Israel Talav, was built in the 18th and 19th century by influential families with administrative clout. An important source for research for Professor Smita Dalvi was the Bapat family, one of the oldest residents of Panvel, who built three lakes. Pics/Sameer Markande

To Mumbaikars with the living memory of travel before the Mumbai-Pune Expressway was built, Panvel is the town sandwiched after the last McDonalds at Kalamboli and the famous Shree Datta Vada Pao Centre at Palaspar Phata. Now, the Expressway flies over it and all you see are the squat squares of new buildings with the balconies the size of bird perches. Its only avenue of interest now is that it is the site of the upcoming airport and a large train terminal.

However, the city has been an important trading town and port in the Raigad district. Panvel Taluka is well-known as the rice-bowl of the region, growing many varieties, one of them even named after the town. Its urban form and architectural heritage dates back to the 18th century. It has been home to a population of Konkani Hindus and Muslims, Dakkhani Muslims, Bohris, Koli fisher folk, and the Bene Israeli Jews, among others. Each community has left behind a place of worship—the Ekviradevi mandir of the Kolis, the Dar-ul-Imarat of Bohra masjid, several temples to Mahadev mandirs with stone deep-malas (stone pillars with carved lamps, to be lit at festivals) and Maratha-style shikara, a Lingayat samadhi, Jama Masjid and the Beth-El synagogue.

The Beth-El synagogue of the Bene Israelis. These are Marathi-speaking Jews of the Konkan Region, and were popularly referred to as Shaniwar Tellis (Saturday oil pressers) due to their custom of observing Shabbat. Pic/Sameer Markande

Even 10 years ago, one could see excellent examples of Kokani-style timbre architecture, with tiled sloping roofs and stone masonry. Domestic architecture consisted of wada-structures, town houses, bungalows, and even Art Deco apartment blocks, such as the Ismail Manzil.

One would be pressed hard to find anyone who remembers or knows any of this, even after living here for decades. And then you have Professor Smita Dalvi, founding faculty at the MES Pillai College of Architecture in Panvel, who has been putting together information and pictures to document this history. The result is a new book, Panvel: Great City, Fading Heritage, which she has co-authored with Sonam Ambe. In it, she has tried to distill the natural history, mythology and human history of the town. Expressed with archival photographs and illustrations, the book is both in English and Marathi.

Dhootpapeshwar Factory, which manufactured ayurvedic medicines, was founded in 1872. In the 19th century, it enjoyed the reputation of being the best option for employment. A small museum to Ayurveda now takes up the ground floor. Pic/Panvel—Great City, Fading heritage

“The general perception for even the residents of New Bombay is that it’s like tabula rasa… nothing existed earlier. In the Raigad part of Navi Mumbai, there are two historical towns—Uran and Panvel,” says Dalvi. “Panvel is a medieval town. By the early 18th century, it was established as a trading town. Its port dated back to perhaps the 15th century, and until the mid 1950s, ships would dock at Panvel Bunder, facilitating travel of people and goods.”

Panvel Bunder on the Panvel creek (as the Gadhi river flows from the Matheran Hills and meets the creek) is closer to the Gharapuri island, which we know as the Elephanta caves. By road, the Sion-Panvel highway concretised and widened an existing route to the Deccan, which on the other end, stretches to Thane. Cutting across the length of New Panvel is the Matheran road that ends at Dodhani village at the foothills of the hill station. It used to be an expanse of paddy fields growing Panvel rice as far as the eye could see; today, a blade or two of grass is visible amongst new residential constructions, even towers, in Sukhapur.

Mahadev temple, Khandeshwar Talav

Dalvi moved to Panvel from Mumbai 25 years ago. “As an architect, we knew that significant heritage existed here. Researching this history helped me become a Panvelkar,” she says. In the early 2000s, Dalvi led a heritage listing project sponsored by MMR-HCS (Mumbai Metropolitan Region–Heritage Conservation Society), implemented by the MES Pillai College of Architecture. The faculty team identified several heritage sites in the towns of Panvel and Uran.

Around 2000, the faculty put forth a proposal to list the Raigad part of Navi Mumbai as a heritage site and it was accepted. The book is a part of that funded project, published by Mahatma Education Soceity [umbrella body of Pillai college]. Fun fact: Raigad district was once known as Kolaba/Kulaba district. Take that, SoBo.

The dargah of Pir Karamali Shah stands on the banks of Devale Talao. The honour of presenting the first chaddar on the annual Urs is still reserved for the Bapat family, one of the oldest residents of the town

Dalvi poked about the old wadas (traditional homes with a central courtyards), and prodded people to point her to places of interest. Panvel gets its name from the six talavas or lakes:‘Pan’ for water, ‘vel’ for vine. “Each is associated with a place of worship of different faiths, built by prominent citizens of the town.,” informs Dalvi, “The Pir Karamali Shah Dargah, commemorating an important saint, a Deccani-style Jama Masjid affiliated to the grand one, the Bene Israeli cemetery adjoining the Israeli talav. Krishneshwar mandir, and so on. Water is important in every religion—it is used for cleansing, rituals and ceremonies, and these lakes also stored rain water. The ponds were community hubs.

Dalvi has documented the fast disappearing heritage. “Most of the sacred structures—whether mosques, temples, or the synagogue—were inspired by local domestic structures—built in timber and tiled sloping roofs. On the outside, it would look like any home,” she says. Many of these are being concretised as donations flow in, some have disappeared and some are being homogenised. “Kokani Hindus had more in common with Kokani Muslims and Bene Israelis—in language, dress and food—than, say, a Bengali Hindu,” she explains. “It was a harmonious co-existence.”

Beig Wada, one of the oldest wadas, was built in 1880 by Dakhani Muslim Yakub Isab Beig. He was a prominent businessman and also built the Mominpada Masjid

across the street

In the past two decades, people are aligning with the larger community identity. For instance, the Jain Derasar is in the process of becoming a marble edifice with a staggering dome.

Others have been engulfed by concrete construction or lie decaying. The triangular Jewish cemetery, for instance, is as large as a traffic island. It holds 25 to 30 graves, and has no boundary or assigned caretaker. Recently, it was cordoned off by barbed wires, with no entry point. “The older graves,” explains Dalvi, “have inscriptions in Marathi and Hebrew. The newer ones have inscriptions in English too. On her husband’s tombstone, Rubybai Benjamin Chincholkar wrote a poem of love in Marathi, comparing her husband to Rama who always kept his word. The synagogue, built in 1849, has a reputation for fulfilling wishes and the odd tourist bus still stops by for pilgrimage. The synagogue was a mud and brick structure until it was damaged in floods of 2005. The neighbouring Muslim tradesmen donated money to have it stone clad.”

Adjoining the Israeli Talav is the patch of land donated by Sheth Karamshi to the Bene Israeli community

Bazaar Peth, the old market spine, still exists and is still a commercial centre. The roads leading in and around it, unfortunately, are of the same width they would have been for cart traffic. The main street, just about wide enough for two auto rickshaws, snakes through old Panvel. “The medieval streets layout is unable to cope with the recent spike in urban growth,” rues Dalvi.

Besides the paddy fields, another agrarian inheritance are mango orchards. “CIDCO has built boundaries around many of them, and turned them into public parks. So they are preserved in some way.”

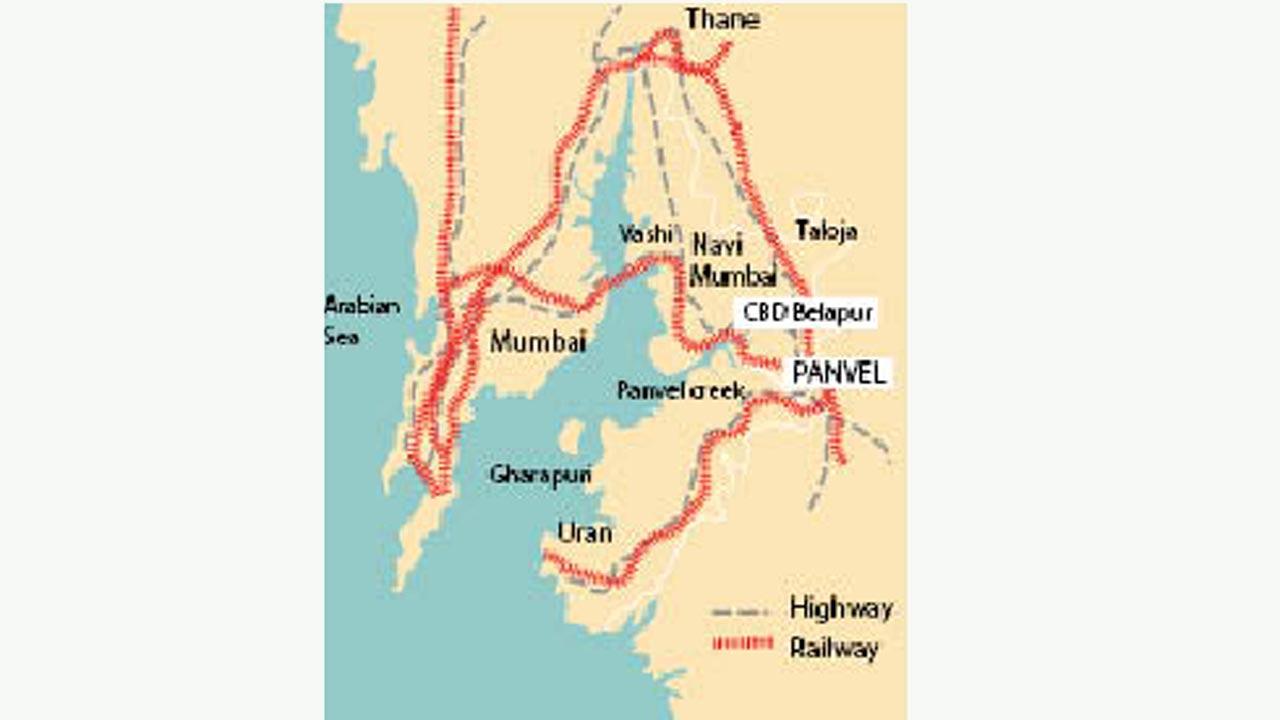

Train and road connectivity to Panvel (marked in red) traced old trade routes to the medieval era city. Panvel has been accessible by road, sea and rail… and soon, by air. Map/Uday Mohite

The book was published just before the pandemic, and Dalvi hopes to see it in bookstores soon. “We plan to distribute it in schools,” she adds, “We also assign projects to the architecture students to research some these spots to keep them relevant. The history of Panvel is the history of its communities. It may not be of importance to the larger state or country. Its talavs and shrines carry the stories and memory of the place. Most of it was preserved orally.”

Losing a place’s historical memories is like losing memory, according to her. “I come from the point of view of tangible, physical structures [as a professor of architecture],” she says. “When a heritage structure is removed, you lose a community’s history. Which is worse. It’s like being a person without past memories.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!