When multi-hyphenate wasn’t a thing, MF Husain was living the virtue. Before his illustrious career as an artist, he made iconic designs for a SoBo nursery furniture store. Mid-day digs up gems of contemporary art history from a quaint collection on display at the ongoing Art Mumbai fair

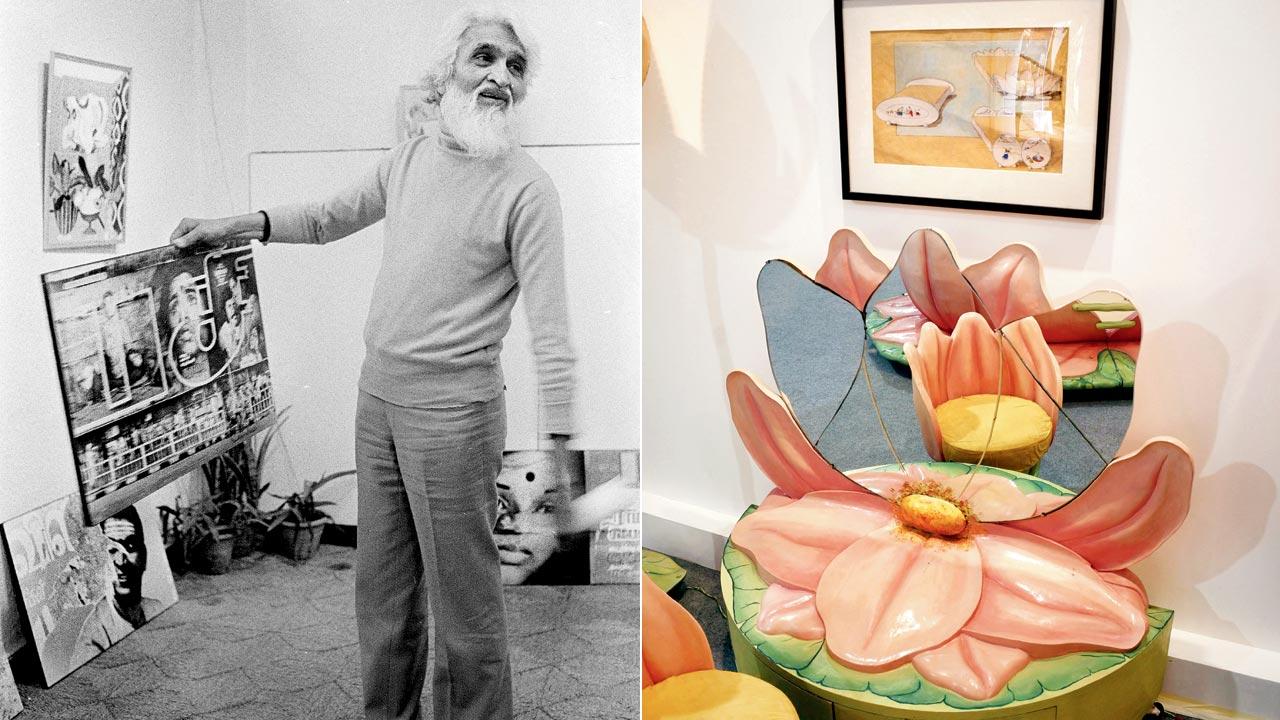

The 80-year-old, original ‘Lotus Suite’ commissioned by Rani Savita Kumari Devi of Katesar. Pic Courtesy/Saffronart Foundation

Right from its opening day, Mumbai’s first ever art fair imbued the grounds of Mahalaxmi Racecourse with an infectious energy and spirit, as attendees went from stall to stall and curators prepared for the weekend to come. A walk into the stall of Saffronart—the auction house whose founders have co-organised the fair—was a pleasing contrast. It was defined by a sense of calm, punctuated only by the occasional whisper—fitting for the nursery furniture set on display there.

Built using a wood, cloth and paper material palette, this 80-year-old ‘Lotus Suite’ is no ordinary bedroom: It comprises a dressing table whose mirror is cut into petal shapes; a cupboard styled like a flower bud; a standing lamp whose lampshade is akin to petals that are opening up; and a bed frame with a lotus stem emerging from its side, poised above to hold a mobile. The distinctive design of this nursery set is further elevated by the pastel hues of pink and green it is painted in, and the attention to detail.

MF Husain in the 1980s. It was at Fantasy that the artist began developing an indigenous aesthetic. Pic/Getty Images; (right) The Lotus Suite’s miniature dressing table with a petal-shaped mirror. Pic/Sameer Markande

MF Husain in the 1980s. It was at Fantasy that the artist began developing an indigenous aesthetic. Pic/Getty Images; (right) The Lotus Suite’s miniature dressing table with a petal-shaped mirror. Pic/Sameer Markande

Above the dressing table is a sketch depicting a designer’s vision for this exquisite furniture set—a designer who India would later know as MF Husain.

The Lotus Suite and accompanying drawings are part of Saffronart Foundation’s presentation at Art Mumbai, titled The Fantasy Collection, which gives us a look into a lesser-known period of Husain’s life. Before he joined the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group and became an established artist, he worked for seven years at Fantasy, a family-run nursery furniture enterprise. “The virtuosity is very much present,” critic and curator Girish Shahane tells mid-day. “One thing he does is, he takes from sources but he never copies, which is very different from what most artists do. He’ll always add something of his own. I’ve looked at the reference images and seen how he transformed them.”

Husain’s previous jobs included painting scenery for film sets and producing cinema hoardings. An old Sotheby’s catalogue tells us that he quit working on hoardings after the birth of his first son, Shafat, for want of a stable monthly salary—R25—at Fantasy, formerly called Rhymeland. The stall at the fair is only a taste of the archival material and artefacts preserved by the owners, the Moizuddin family. Want to see more? Head to Saffronart’s Prabhadevi outpost where a display is on until the end of November.

A Cherry Blossom-themed suite—one of the highlights of Husain’s time at Fantasy. Pics Courtesy/Saffronart Foundation

A Cherry Blossom-themed suite—one of the highlights of Husain’s time at Fantasy. Pics Courtesy/Saffronart Foundation

This material is considered some of Husain’s earliest output. “It’s an archive that shows the birth of an artist at a particular time in history—an archive that shows us how he developed into an artist. It’s incredibly rare to have that for any artist, especially in such enormous detail,” says Minal Vazirani, co-founder of Saffronart.

In some ways, the designs he created in the 1940s were foundational to his career, and echoes of them can be found in his later output. Vazirani brings our attention to the wood “toys” Husain created. “If you look at his painted wood ‘toys’, the idea for them came from the designs he made for Fantasy,”

she explains.

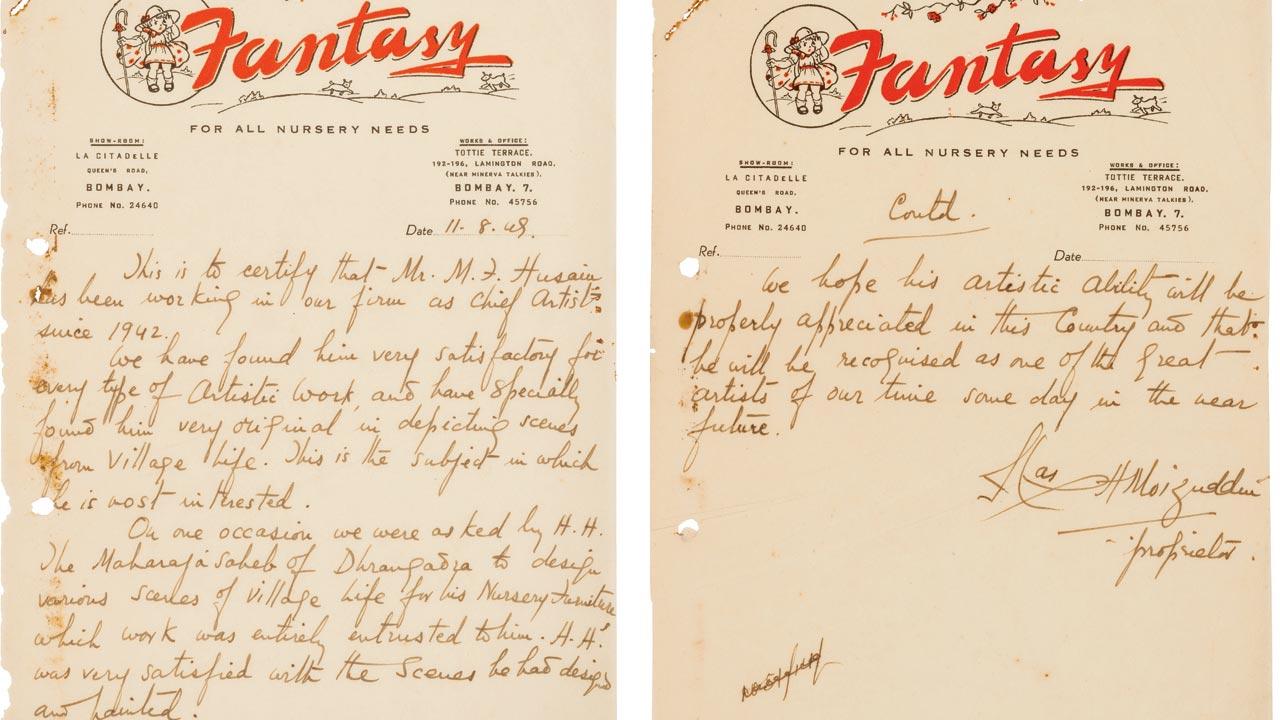

A letter of recommendation from Fantasy to Husain, recognising his artistic genius

A letter of recommendation from Fantasy to Husain, recognising his artistic genius

The motive behind The Fantasy Collection, curated by Chatterjee and Lal’s founder Mortimer Chatterjee, is to explore the themes developed at the furniture business under Husain, which speak to the concerns of the time in the Indian art and design fields. Consider, for example, the shift in aesthetic adopted by the artist in the templates created to be pasted on pieces of furniture.

Shahane notes that although we cannot determine the precise dates when the drawings were made, a trajectory does emerge. “The early pieces are renderings of images from European and American films and children’s books. Among the common reference points are Walt Disney’s full-length animation features,” he writes in a text panel. Even the children imagined playing in the designs of suites have a cherubic look, reminiscent of European art.

A letter from 1944 cited in the exhibition, that the artist wrote to a friend in Baroda, tells us that Husain and Elias Moizuddin collectively decided that the same designs could not be constantly repeated, thus turning their gaze towards Indian folklore and villages. “I am going to start replacing Jack and Jill and Humpty Dumpty with stories from ‘Panchatantra’, so much more colourful and meaningful,” Husain writes, in the hope that Fantasy’s clients will like the new designs, “As you know most of our clients are more English than the English.”

“[Husain] gradually stamped his personality on the job by incorporating stories that were geographically and culturally closer to India,” Shahane writes in a text panel. The icons from these stories include Sindbad the Sailor, Aladdin and Ali Baba. Other images, too, were created with an unmistakably Indian aesthetic, such as a little girl wearing a sharara, or another playing with a fawn and turning a small charkha with her hand.

“The look of toys and furniture at the time was quite Anglicised, as was the customer base. So, it must have been a very radical shift,” Shahane comments.

Vazirani notes the linkages between Husain’s search for an indigenous aesthetic and that of his contemporaries at a crucial time in Indian art and history. “It happened at a time when India was emerging as an independent nation. All of his contemporaries too were finding an emerging Indian aesthetic in a modernising India.”

Mortimer Chatterjee’s juxtaposition of Husain’s designs with snippets from Fantasy’s history paint a picture of the artist’s world in the 1940s, around the time of Independence. Situated on Queen’s Road, now known as Maharshi Karve Marg, Fantasy’s showroom was frequented by the who’s who of Mumbai society; a 1947 page from the visitor’s diary tells us that a Mrs Nadkarni, a Mrs Petit and a Mr Tyebjee visited on the same day, from the neighbourhoods of Breach Candy, Cumballa Hill and Churchgate respectively. The very idea of a nursery within the Indian home drew from contemporary psychology and sociology, and a globalised perspective on raising children.

In the late 1940s, a commission came from a royal house: The late Rani Savita Kumari Devi of Katesar asked for the Lotus Suite, which was based on an existing Rose pattern. It would go on to be part of her family’s Mussoorie home, where another Cherry Blossom-themed set would also feature. A text panel tells us about how cherished these sets were to the Katesars: three generations of the family enjoyed them before they became a part of Minal and Dinesh

Vazirani’s collection.

The Fantasy Collection underscores not just the ways in which Husain contributed to the success of a furniture store in Mumbai, but also the path he had begun to carve for himself. His genius at this nascent stage was recognised by his employer Elias Moizuddin—a fact that is unusual given the hierarchical nature of employer-employee relationships in India, says Shahane, particularly in the last century. “We hope his artistic ability will be properly appreciated in this country and that he will be recognised as one of the great artists of our time some day in the near future,” Moizuddin writes in elegant penmanship, on a Fantasy letterhead.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!