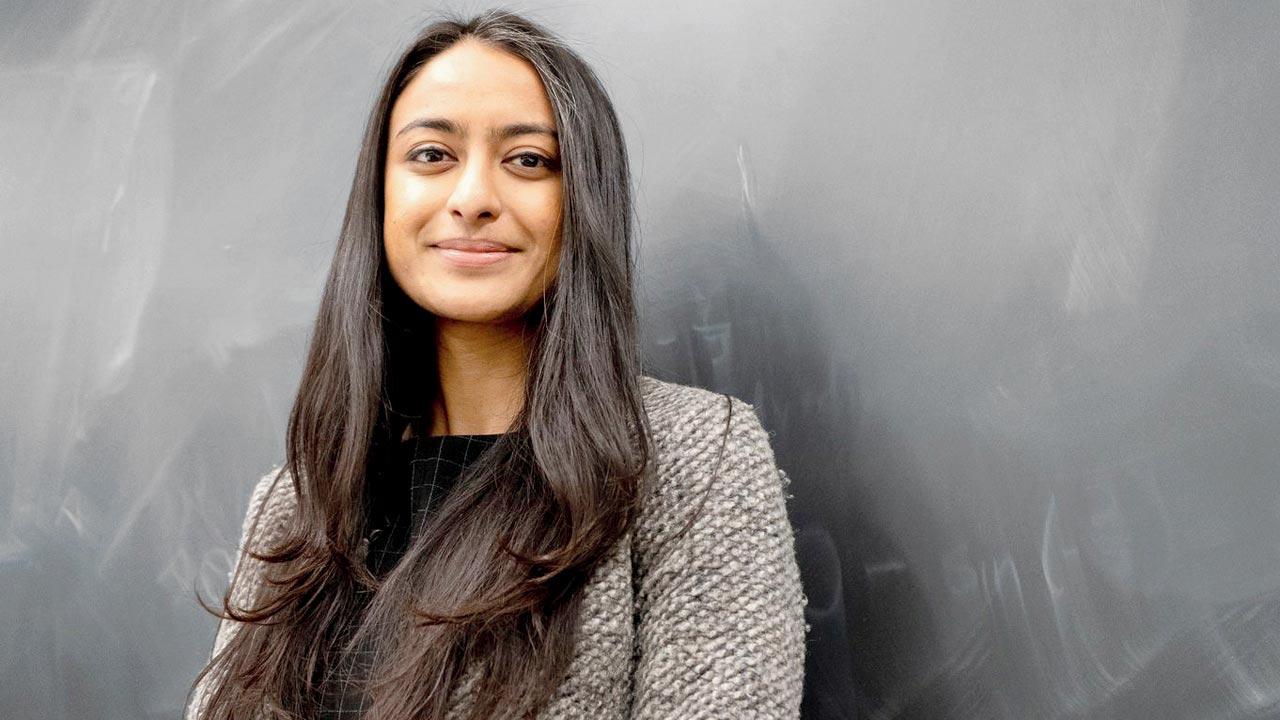

Apsara Iyer, first Indian woman president of the prestigious student publication, tells us why restoration of stolen antiques to their rightful countries is her mission

In her four-and-a-half-years at the Antiquities Trafficking Unit in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, Apsara Iyer helped restore over 1,100 antiquities to 15 different countries

In February, first generation Indian-American Apsara Iyer claimed another milestone for the Indian community already standing on an Everest of spelling bee wins, and so many more exemplary academic achievements—she became the first Indian woman to be appointed president of the prestigious Harvard Law Review.

ADVERTISEMENT

The journal is published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School, and is said to stand first among 143 student law journals for its impact factor. It is among the oldest student-run legal scholarship publications. Iyer is the first Indian woman in its 136-year history to hold the position, and follows such prestigious names as former US president Barack Obama and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Pudhil station, White House.

Iyer grew up in Indiana, born to Tamil parents raised in Wadala; the couple’s parents had moved to India’s financial capital in the 1930s and ’40s from Kerala. The 29-year-old joined the prestigious law school after four-and-a-half-years at the Antiquities Trafficking Unit in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, where she helped restore over 1,100 antiquities to 15 different countries. “Several of these objects were from India,” she says over e-mail, “and I was the lead analyst on many investigations concerning trafficking networks operating in India and Southeast Asia.”

Apsara Iyer

Apsara Iyer

Iyer’s interest in history and antiquities was seeded in high school, when she worked on an archaeological excavation site in Peru. “I began to pursue my studies at Yale with a research focus on the value of cultural heritage,” she says. “During one of my field research projects in India, I had the opportunity to visit a site that had been the victim of looting. I distinctly remember that while I was at the site, someone asked me, ‘What are you going to do about this?’ This wake-up call led me to work in law to address the issue of antiquities trafficking.” Iyer graduated from Yale majoring in Math, Economics and Spanish, and went on to pursue an MPhil in Economics from the University of Oxford.

The destruction of cultural heritage and its effect on people occupied her mind. “This kind of destruction—by looting or other means—is an attack on the identity of a community and, in turn, our common humanity. Cultural heritage represents a shared history, roots, and beliefs.” Her favourite memories from working at the District Attorney’s Office surround organising repatriation ceremonies to return stolen objects to their lawful owners. “Each repatriation ceremony, whether with India or Iraq or Greece, is incredibly moving,” she says. “Although the return of the objects will not recover their original archaeological context, the repatriation allows for a piece of history to journey back to its lawful owner.” One case of satisfying avengement must have been that of hedge fund billionaire and philanthropist Michael Steinhardt. In 2021, he surrendered $70 million of stolen antiquities and was banned for a lifetime on acquiring antiquities. Iyer worked on the case in which 180 antiquities, stolen from 11 countries, were returned to rightful owners in Bulgaria, Egypt, Greece, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jordan,

Lebanon, Libya, Syria and Turkey.

Among the first cases she was assigned at the DA’s office was the one involving a Nataraja stolen from the Punnainallur Temple in Thanjavur. “Over the next three years,” she says, “I worked tirelessly with the lead prosecutor to uncover new evidence, witnesses, and investigative leads. Our work single-handedly resulted in the return of the Nataraja to the Government of India. In such cases, I have seen first-hand how the communities maintained hope and prayed for years that the relics will return.”

Another inspiring moment was being able to work on a case involving a mother goddess statue stolen from a site in Udaipur that she had visited in 2013 for research as a student at Yale.“I photographed the temple post-theft,” she says, “and met with local witnesses who still remembered the statues. Finally, in 2022 nine years later, we were able to recover one idol and it is awaiting repatriation to India.”

On the personal front, Iyer enjoys looking at art and boxing, a sport she trained in for a charity event while living in New York.

Also Read: Four trailblazing women on sexuality, desire, and bodily autonomy

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!