Prayaag Akbar’s second novel offers a sharp portrait of young India reeling from the thrills, delusions and manipulations of a hectic digital landscape bandying concepts of nation and nationalism, AI and virality

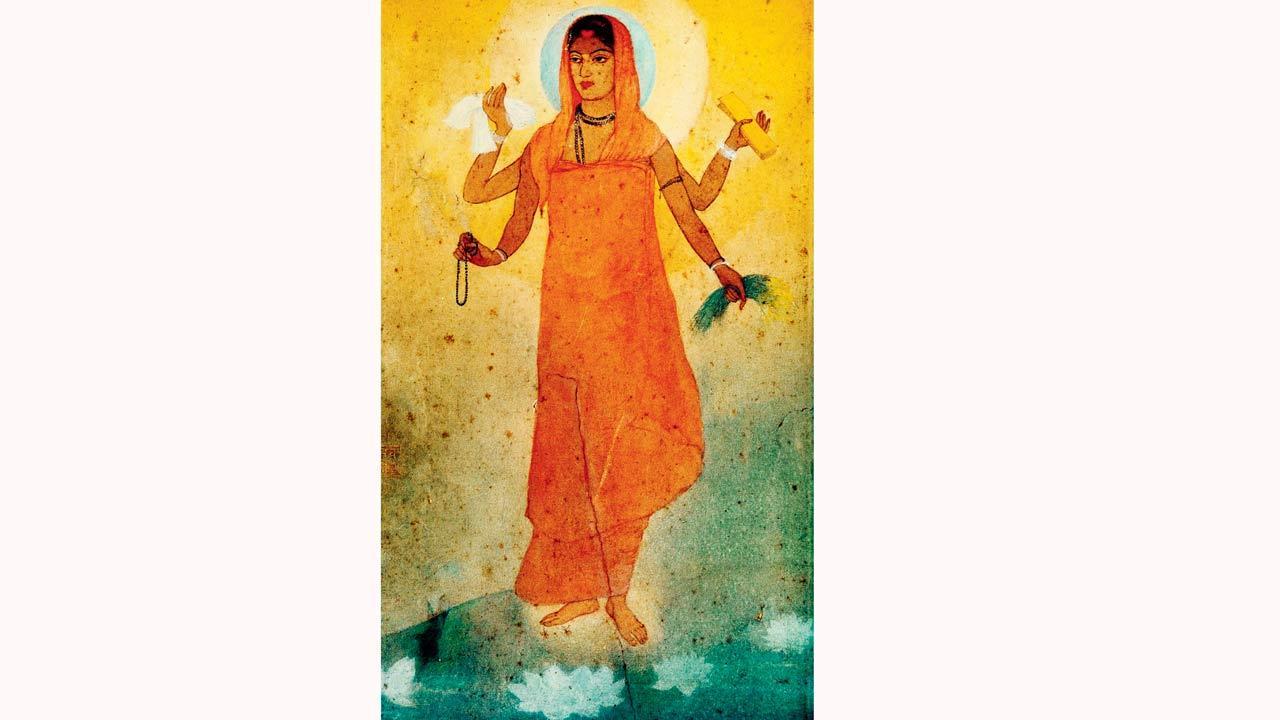

This original 1905 painting of Bharat Mata by Abanindranath Tagore plays a key role in the crafting of a video clip that propels the story in Prayaag Akbar’s new novel. The painting is one of the earliest visualisations of ‘Mother India’, where she is depicted as a saffron-clad sadhvi holding a book, sheaves of paddy, a piece of white cloth and a rosary in her four hands. Pic/Wikimedia Commons

In Prayaag Akbar’s new novel Mother India (Fourth Estate, R499), a young man employed in a right-wing content creator’s dingy basement studio is assigned to work on a video clip intended to respond to a presumed threat to the nation from “PhD-waale. Jihadis. Khalistanis. Maoists and missionaries”. Referencing a famous 1905 portrait of Bharat Mata by Abanindranath Tagore and with some help from an AI app that morphs images of real women taken off the internet, he animates a representation of the figure of Bharat Mata imposed on the map of the country. Of these representations, Akbar writes in the book: “She stood with her feet together at the bottom of the peninsula, arms reaching out so that her body became the body of the nation. Her torso appeared over the Gangetic plain, the saree or sometimes her tresses flowing as the great river would. The haloed head and mysterious placid face were invariably positioned over the northern reaches: Kashmir.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Akbar, who writes in the book’s Acknowledgements of encountering the concept of the “geo-body” in cultural historian Sumathi Ramaswamy’s The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India, tells mid-day, “I was drawn to the symbol of Mother India because it is such a deeply emotive symbol for so many of us. I find it very powerful myself: the appeal to our instinctual need to protect the mother—who can reject that call?”

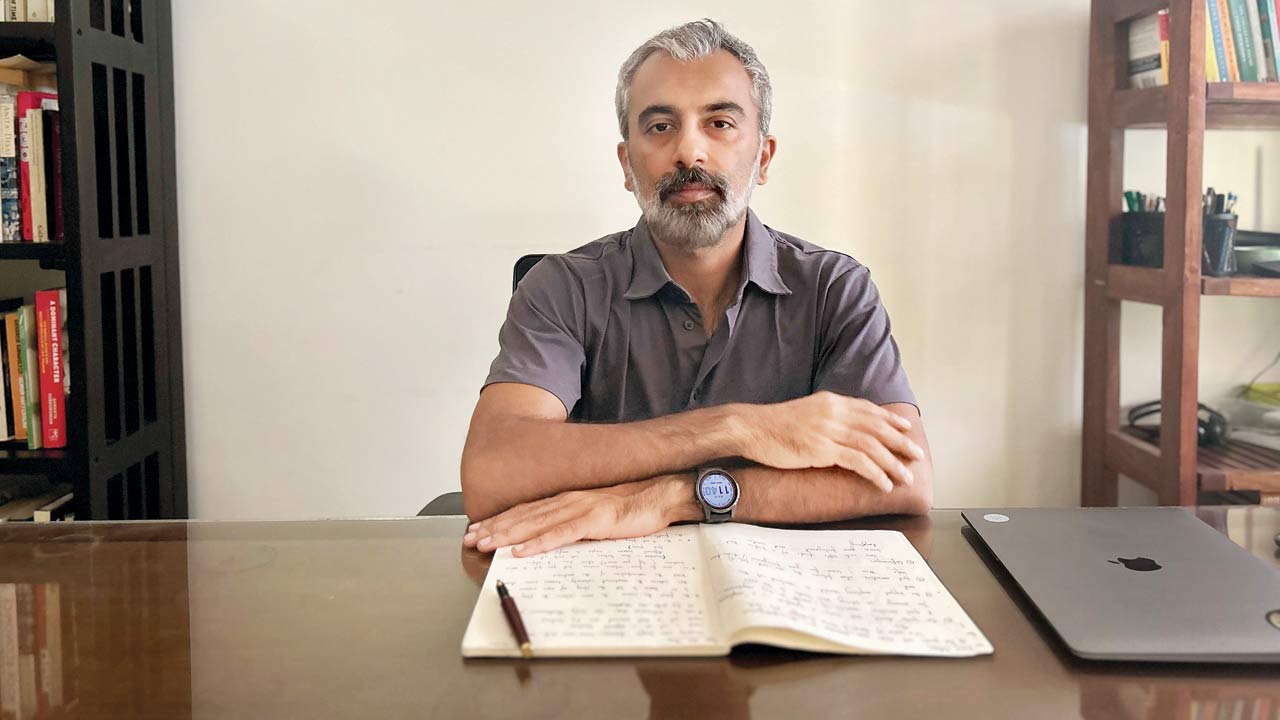

Prayaag Akbar says that his second novel grew from the story of a young man in love to slowly encompass his growing concerns about technology impacting human lives

Prayaag Akbar says that his second novel grew from the story of a young man in love to slowly encompass his growing concerns about technology impacting human lives

The Mother India icon has a powerful presence in the anti-colonial struggle and in our nation’s artistic history,” he thinks. “As I learned from Ramaswamy’s book, once the Mother India image was laid upon the geographic body of India, it acquired a different kind of resonance for the people combating colonialism.”

Akbar’s novel, his second after the critically acclaimed Leila, situates its young characters in an urban India—itself riddled with concerns around migrants and overbuilding—where the pressures of earning a living and finding love are compounded by the effects of a volatile political environment and a hectic, fast-changing, invasive and exploitative digital landscape that both connects and deeply isolates people.

It grew, Akbar has noted, from the story of a young man in love to slowly encompass his growing concerns about technology impacting human lives. Three years, he says, went in the writing of various drafts which were substantially different in both matter and length. “As I wrote, and thought more about these characters, and their lives began to feel real to me, various threads and connections that I’d been struggling for years with seemed to come together in interesting ways,” Akbar notes. “I realised I did not have | to focus on a particular technology or platform, that the truly interesting thing is how all that information and noise is affecting our inner lives”.

Akbar has had a career in journalism before he pivoted to fiction. Mother India which incorporates contemporary incidents in the country including attacks on journalists and fiery speeches from student union heads at Jawaharlal Nehru University, straddles both the real and the constructed, where the lines between truth and fiction often appear significantly blurred. We wonder how much his prior work and instincts as a journalist have informed this book and its primary concerns. “I have always been interested in the political sphere. I read a great deal of non-fiction. My fiction is naturally about the things I’m interested in, it is a reflection of the way I see the world,” Akbar tells us. “Though they are such different beasts, I don’t view my years in journalism as sharply distinct from my time writing fiction. I was learning how to be a writer then and I’m still learning how to be a writer.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!