The legacy of the sujni has whittled down to the looms of its last two weavers, who have found a comforting nest in a heritage building where Bharuch’s distinctive cubist woven quilt craft stays warm

The Sujni Co-operative Society in Bharuch comprises the last two weavers—Rafeeqbhai and Muzakirbhai Sujniwalla—who know the craft. Pics/Vicky Joshi

The irony is that even in its heyday in the middle of the last century, the sujni quilt was barely used in Bharuch. It’s too light for winter and too heavy for summers in Gujarat. About 400 weavers toiled away on enormous looms with 600 taars that make up the warp and weft, two people at each loom.

Now, there are only two weavers on the looms at Sujni Co-operative Society that weave them in the nearly 100-year-old building run by the Seth Jeejeebhoy Dadabhoy Trust. Rafeeq Bhai is approaching his 70s, and Muzakir Bhai, his 60s. Both go by the last name Sujniwalla, and have no apprentices—not even offspring—who will carry forward this skill that was once synonymous with the town. “If you came to Bharuch, you had to go back with a sujni quilt,” says Malabar Hill resident Pilloo Ginwalla, who has been instrumental—along with other members of the Inner Wheel club—in starting the looms up again.

The building lay unused for 40 years before it was restored by the ladies of the local Inner Wheel club. It is now a training-cum-production centre for sujni craft

The building lay unused for 40 years before it was restored by the ladies of the local Inner Wheel club. It is now a training-cum-production centre for sujni craft

Sujni is unique in this aspect: Squares and rectangles are woven line by line, manually stuffed with cotton, woven closed and onwards. A double quilt takes about three days to weave and is stuffed with two to three kilos of cotton wool. The combination of arrangement of squares and rectangles in different colours makes up different patterns. The skill came from Assam, via imprisonment in the Andamans in the 1800s. A Bharuchi man was serving ‘kaala paani’ in the island’s prison and a fellow inmate from the eastern state taught it to him. He brought it to the then village, where it flourished.

This twilight of the craft started with the restoration of the building that served as the Bal Mandir nursery where Pilloo and her husband incidentally studied. It was built in 1926 and comes under the aegis of the Seth Jeejeebhoy Dadabhoy Charity. It lay decrepit for 40 years before the ladies of Bharuch’s Inner Wheel club made its conservation a passion project in 2010. Ginwala was serving her second term as the club’s president then. “The idea first,” she says, “was to run classes to read, write and count for school dropouts who do small-time jobs such as running a chai tapri. They can’t be enrolled in school as per their age because say, they belong in Class V, but they don’t have the skills of their peers.” This gap also demoralises them from continuing to go to school.

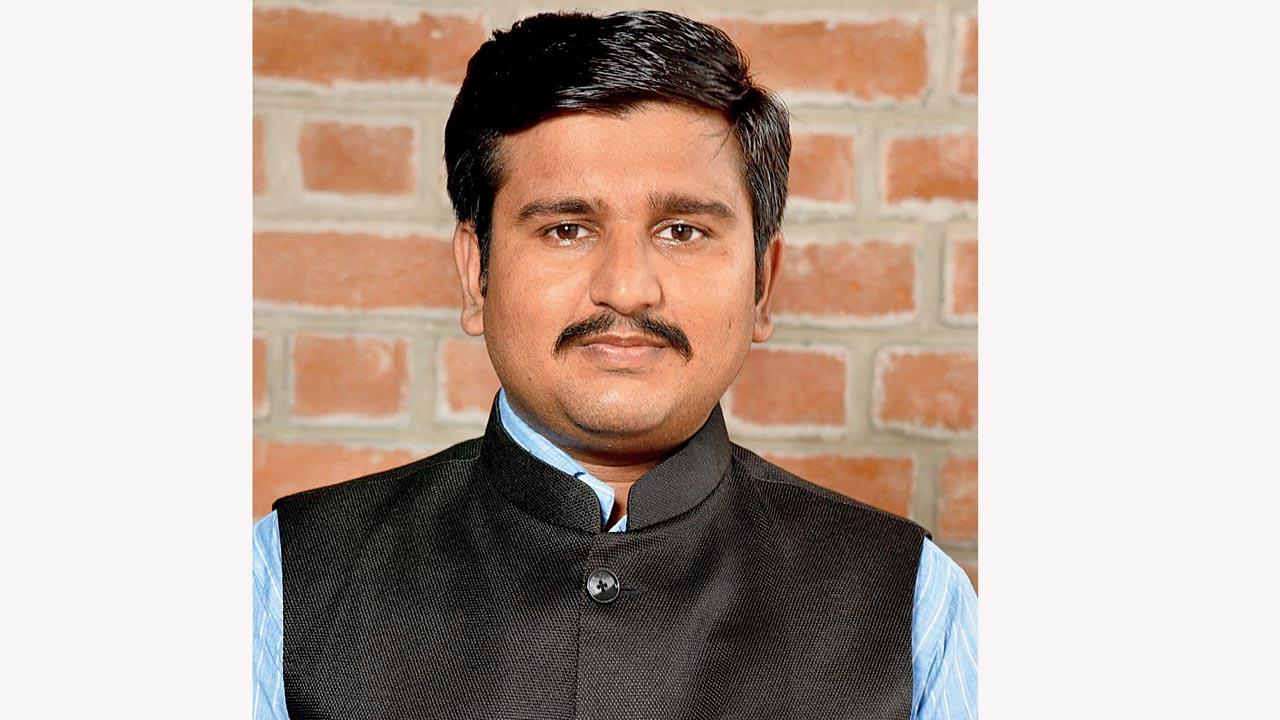

Niravkumar Sanchaniya, a Mahatma Gandhi National Fellow who helms Project ROSHNI (Revival of Sujani and Neoteric Inclusion of Artists)

Niravkumar Sanchaniya, a Mahatma Gandhi National Fellow who helms Project ROSHNI (Revival of Sujani and Neoteric Inclusion of Artists)

However, the classes could not continue because the building is in a Muslim locality and Hindu parents hesitated to send their children here. A nursery still runs under a Muslim trust on the ground floor, and the top floor is taken up by the Sujni Co-operative Society, which formed last year.

In 2022, the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship got involved in the project and Ahmedabad resident Niravkumar Sanchaniya has been deeply invested in formalising the craft and expanding its appeal through Project ROSHNI (Revival Of Sujani & Neoteric Inclusion of Artists).

The intricate patterns of the sujni come from arranging a combination of squares and rectangles, each in a different colour. The building, built in 1926, used to house Bal Mandir nursery that Pilloo Ginwalla attended

The intricate patterns of the sujni come from arranging a combination of squares and rectangles, each in a different colour. The building, built in 1926, used to house Bal Mandir nursery that Pilloo Ginwalla attended

“We are developing it under the One District-One Product scheme of the government,” says the a Mahatma Gandhi National Fellow, “and formation of the co-operative society was the first step. We have applied for the GI (geographical indication) tag and the Handloom mark which will boost its value in the export market. We have also started training other candidates to keep the skill alive.” Right now, there are students in the age group of 18 to 50+, seven of them women. They have been docmenting the many patterns of the sujni at the production-cum-training centre. Students from the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) has also been roped in to help with quality improvement and product development to increase the appeal of the flully blanket.

Because of its bulk, the sujni is hard to store and put away. It was primarily carried by pilgrims going on Haj, serving both as a mattress and coverlet. To make it commercially viable, Ginwalla came up with the idea of sling bags, coasters, runners, throws for sofas and shopping totes. The original parrot green, rani pink, turmeric yellow combinations are also being toned down to sky blue and ecru to make them viable for the international market, where the price runs into hundreds of dollars and euros (as it should). In India, the Bharuch quilt is sold through the Sujniwallas’s homes and a couple of retail stores in town, starting upwards of R4,000 depending on intricacy of pattern.

Only four hours away from Mumbai by train, sujnis should make their way to tony lifestyle stores here (and bring along with them, the equally pillowy

Bharuch bread).

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!