Eighty-four sarees telling nine stories—the second edition of a stupefying exhibition helmed by Bengaluru’s The Registry of Sarees succeeds in celebrating the history and beauty of the country’s indigenous garment

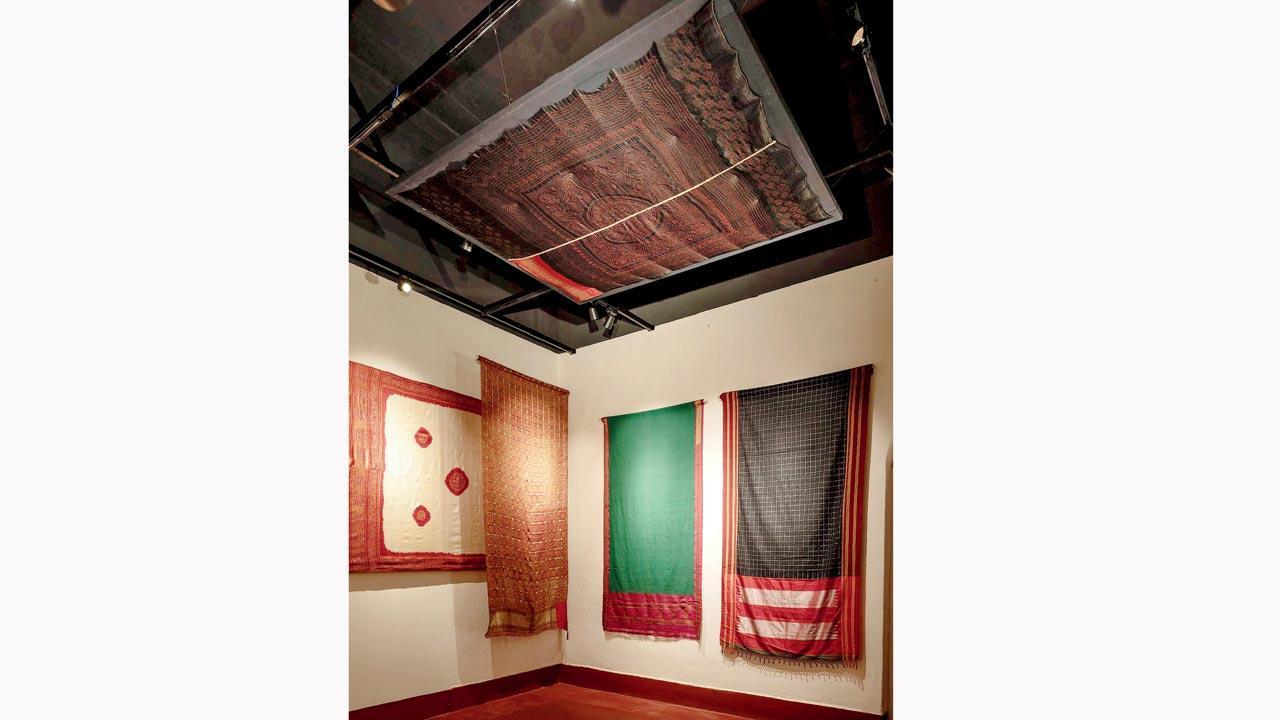

The Red section at the Red Lilies, Water Birds exhibition depicts variations of the hue represented in textiles across India. (Right to left) Karnataka Ilkal, Gadwal saree, Gharchola and Panetar highlight the technique of tie-dye using seeds. The textile that hangs from the ceiling is a rai dana Bandhani odhna, made using mustard seeds in gajji silk. It belongs to the Kutchi Memon community. Pic Courtesy/Pallon Daruwala

The Indian handloom industry, it seems to me, rests on one premise: the saree. As long as that unstitched but very structured cloth remains in abundant usage, all is well.”

The Indian handloom industry, it seems to me, rests on one premise: the saree. As long as that unstitched but very structured cloth remains in abundant usage, all is well.”

ADVERTISEMENT

This visceral quote in the foreword to The Master Weavers: Festival of India in Britain, Royal College of Art 1982, by Martand Singh or Mapu as he was widely known, connects the culture of the saree with the greater purpose of the nation’s economy and well-being. Mapu, who remains India’s beloved textile revivalist, led a pioneering series of exhibitions titled, Vishwakarma—Master Weavers for the Festivals of India in the 1980s and 1990s.

Stepping outside the formal gallery spaces, Red Lilies, Water Birds—The Saree in Nine Stories show unfolded inside a bungalow in Bengaluru recently. With a lively back-and-forth between chronicling aspects of the saree’s history, socio-economic, cultural and political scenarios, and personal stories shared by the visitors, the relaxed environment made the walkthrough as informative as accessible emotionally

Stepping outside the formal gallery spaces, Red Lilies, Water Birds—The Saree in Nine Stories show unfolded inside a bungalow in Bengaluru recently. With a lively back-and-forth between chronicling aspects of the saree’s history, socio-economic, cultural and political scenarios, and personal stories shared by the visitors, the relaxed environment made the walkthrough as informative as accessible emotionally

“Mapu’s contribution has huge depths and continues to be relevant today,” said Ahalya Matthan. “There is survival at different levels; of materials and skill sets, cultural and personal identities [with the saree enduring],” explained the founder of The Registry of Sarees (TRS), a Bengaluru-based research and study centre built on the belief: “The saree is our compass”.

More than a glimmer of this thought came through in TRS’s iteration of, Red Lilies, Water Birds—The Saree in Nine Stories, an exhibition held in Bengaluru recently tracing the diverse and remarkably enduring journey of the saree spanning a period from the late 19th to the early 21st century. The first edition in 2022 was organised in association with The Kishkinda Trust at Anegundi village in Karnataka, and showcased 108 sarees sourced by TRS and curated by Mayank Mansingh Kaul.

The three textiles made in Austria (gleaned from the stamp and company name woven in as R Jager & Co) initiates a conversation of why and when? Was Austria trying to create a marketplace in India like the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese had? Was this happening in the midst of the First World War (1914-1918) where the Central power subtly tried to make its market in the colonies of Allies, especially given that Germany had taken over the production of synthetic dyes? Irrespective of the reasons, the yardage and the sarees in the image replicates the Indian aesthetic in terms of embellishment and colour palette. The Indian concept of the pallu (drape) is missing, and the proportions don’t align with conventional Indian standards

The three textiles made in Austria (gleaned from the stamp and company name woven in as R Jager & Co) initiates a conversation of why and when? Was Austria trying to create a marketplace in India like the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese had? Was this happening in the midst of the First World War (1914-1918) where the Central power subtly tried to make its market in the colonies of Allies, especially given that Germany had taken over the production of synthetic dyes? Irrespective of the reasons, the yardage and the sarees in the image replicates the Indian aesthetic in terms of embellishment and colour palette. The Indian concept of the pallu (drape) is missing, and the proportions don’t align with conventional Indian standards

A bungalow on Hayes Road that once belonged to the Travancore royal family (now home to Kamlesh and Dinesh Talera of the Mysore Saree Udyog) was the Bengaluru venue, and prompted a sense of intimacy that a typical museum can’t. “We are consciously moving away from ultra-precise, almost sterile museum-going experiences, and a never-ending list of restrictions; no photographs, no sharing personal stories [on sarees] or asking questions. As Indians, we are inclusive. We like sitting at the same table, so to speak, and this table is about sarees,” Matthan explained.

An inventory of 84 sarees and unstitched textiles was divided in stories of Saree and the World, Varanasi and the World, Varanasi and India, Metallic Textiles of Deccan and South India, Metallic Textiles of Deccan and Gujarat, Checks and Stripes, Ikat, Red and Kora. Travelling from one room to another, moving between one saree story to the next unravelled disparate threads and constructed a broader cultural narrative—exalting textiles as builders of civilisations, catalysts of craft advancements, keepers of sacred tradition and icons of freedom.

This Baluchari butidar silk saree with the kalka (paisley) motif has an inscription of the weaver, Dubraj Das from Mirpur (present day, Bangladesh). In the midst of protests against mill-made “Made in Manchester” and “Made in Austria” textiles flooding the Indian market, this piece upholds the importance of skill, attested by the weaver by signing his name as if in protest. The signature asks us to think whether the weaver considered himself an artist

This Baluchari butidar silk saree with the kalka (paisley) motif has an inscription of the weaver, Dubraj Das from Mirpur (present day, Bangladesh). In the midst of protests against mill-made “Made in Manchester” and “Made in Austria” textiles flooding the Indian market, this piece upholds the importance of skill, attested by the weaver by signing his name as if in protest. The signature asks us to think whether the weaver considered himself an artist

One of the show’s curiosities was a Khadi saree embellished in aari embroidery and dyed in natural Indigo. Ponduru, a weaving centre in Andhra Pradesh, came to the forefront during the emergence of the Swadeshi movement in 1905 and Khadi movement in 1918. Women played an active role in the freedom struggle, yet did not restrict themselves to use of plain Khadi saree, embellishing them instead with hand embroidery and natural dyes.

Additionally, the mixing of thematic groupings encouraged jolts of non-linear craft dialogue and exchange in India, effectively freeing the saree from the state-wise labels. “That was our curatorial intention… to open doors to the whole saree multiverse,” added Barkha Gupta, the exhibition’s curator and designer. “A saree is an amalgamation of different alliances and influences and we wanted the viewer to make their own connections as they discovered the crossover of various weaving traditions across regional clusters, sometimes bringing two stories together in one saree—a Paithani besides a Chanderi, for example.”

Parul Mendiratta, Aadya Swaroop Naik, Avinash Sheena, Vishwesh Surve, Barkha Gupta, Preeth Khona, Manasvini Ramachandran, Radha Parulekar and Aayushi Jain from The Registry of Sarees team. Pics Courtesy/Pallon Daruwala

With TRS team since 2020, Gupta, 29, has a background in contemporary art, which she believes helps her look at textiles from an artistic lens. The show’s curatorial researchers, Preeth Khona is an academician, and the 24-year-old Aayushi Jain (the youngest in the team) has a background in archaeology. The show’s assistant designer Vishwesh Surve is an architect, conservation lead Manasvini K Ramachandran is a dancer, TRS collection manager Radha Parulekar is a researcher. “Because the team is young, and with various training and interests, it drives the saree conversation in a direction that is completely contrary to the scholarly approach of the past. Here, the young are getting an opportunity to lead a conversation, which is refreshing; I say this as someone sitting in the audience,” Matthan said.

“With the saree’s identity being tied tightly with ‘tradition’, it has become easy to overlook the range of cultural transmissions that have informed the form and function of the saree today,” Ahalya Matthan, The Registry of Saree

“With the saree’s identity being tied tightly with ‘tradition’, it has become easy to overlook the range of cultural transmissions that have informed the form and function of the saree today,” Ahalya Matthan, The Registry of Saree

Herself a trained perfumer, Matthan’s passion for handloom sarees inspired her to launch the #100SareePact in 2015. The social media campaign took the shape of TRS in 2017. TRS was founded as an interdisciplinary practice to enable design, curatorial and publishing of projects in the area of handspun and handwoven textiles. Their research, study centre and library is open to the public via an appointment. “Our definition of ‘conservation’ is not about building a storage room stuffed with heritage textiles, but about ensuring its longevity by opening our knowledge bank to all. My big learning is not to do anything to provide an answer or solution but to provoke thought.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!