A new documentary on a late artist and poet is a tribute to Bombay, which nurtured his aspirations and love

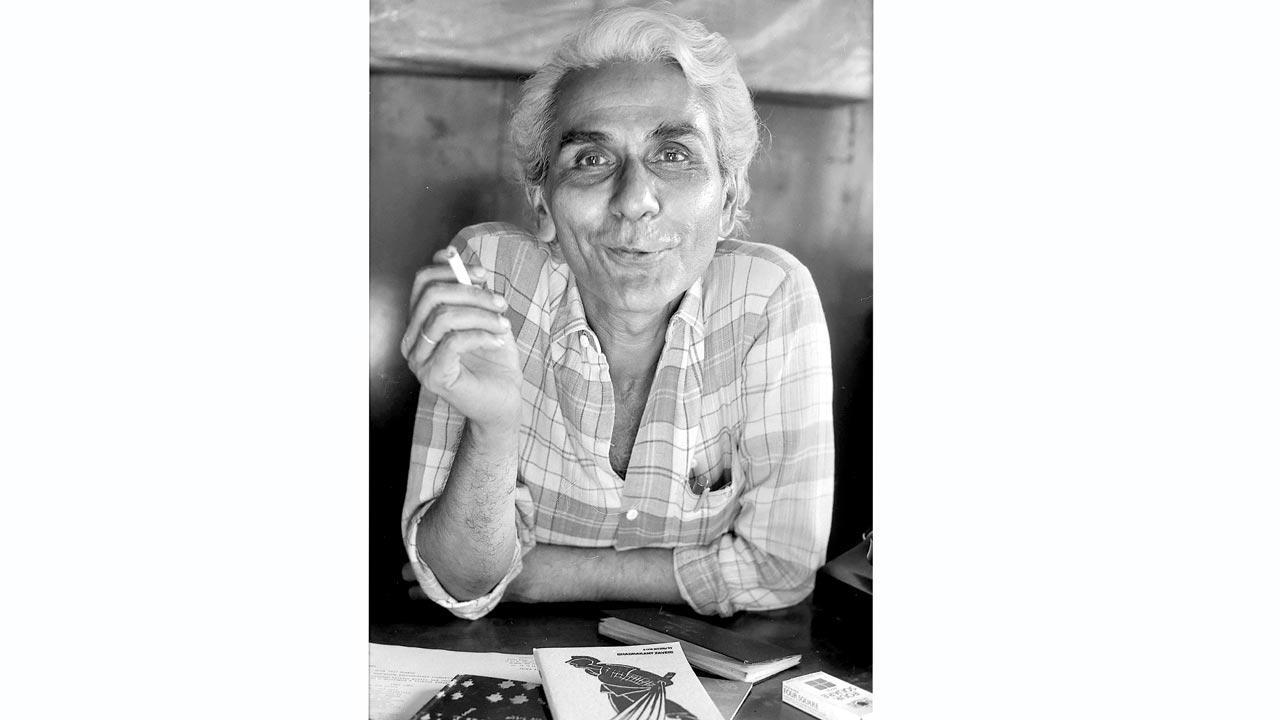

Playwright-poet-actor Bhadrakant Zaveri, 56, was killed in a bomb blast in October 1993. Pic/Bindi Sheth

![]() Aam juvo toh natak natak/tem juvo toh dhak dhak dhak dhak (If you look at it this way, it’s a play/If you look at it that way, it’s life).

Aam juvo toh natak natak/tem juvo toh dhak dhak dhak dhak (If you look at it this way, it’s a play/If you look at it that way, it’s life).

ADVERTISEMENT

Gujarati playwright-poet Bhadrakant Zaveri’s words are throbbing, direct and warm. The artist endeared me instantly in the first few frames of the newly-released 42-minute documentary, How Do I Show The Ocean Space You Carried Inside You. The film is an ode to Zaveri’s writing, his thought process and his connect with the city’s people, institutions and iconic structures. Zaveri’s portrait as a deeply caring lover emerges effectively, and so does his appreciation of natak and dhak dhak.

The documentary is a reminder of yet another bitter reality of the contemporary violence-ridden world—any fateful day could be the last day of our lives. A violent act of terror in any part of the world can permanently damage the lives of unknown unconnected people, just as it happened with Zaveri, who died a premature death in a bomb blast on October 29, 1993 in Mumbai. He was 56 when his legs were blown off from the knees by the blast. Death came too soon, too suddenly, leaving no scope for a proper good bye.

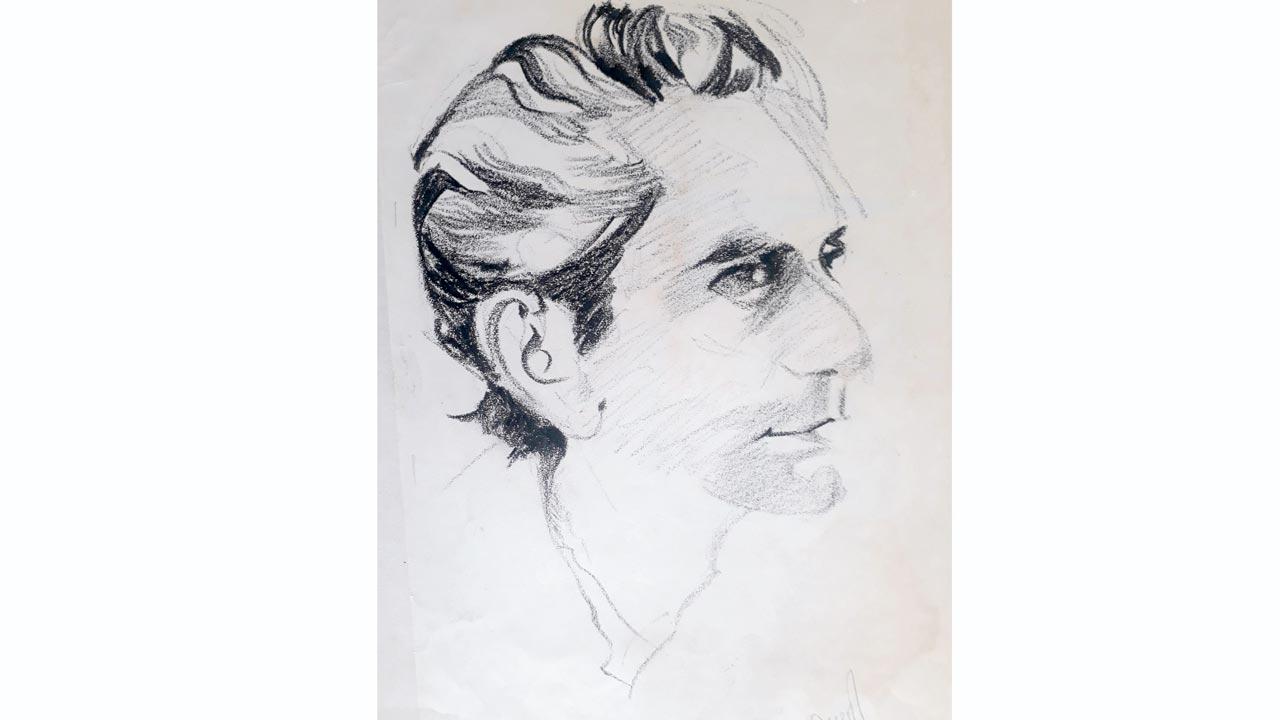

A portrait of Zaveri by Kapadia

A portrait of Zaveri by Kapadia

Renowned visual artist Bharati Kapadia, whose works have been exhibited widely in India and abroad, and who is the film’s presenter (Zaveri’s partner for 24 years who plays herself in the film) shares the scary manner in which a seemingly-ordinary local train journey (Andheri to Churchgate) ended in a pool of blood and splintered bones. The blast occurred at Matunga station, when Kapadia (seated in the adjoining ladies first class compartment of the same train) didn’t realise that very soon she was to witness Zaveri’s bruised-annihilated body. Even before she could digest the shock of locating her loved one in a state of acute pain, railway workers placed Zaveri’s body on a makeshift stretcher. Kapadia has no memory of taking his head on her lap or holding his hand for the last time, as there was no room for touching without causing further pain. A part of her wanted Zaveri to live, and a part of her wondered how could a “dynamo” ever live without standing on his legs. In fact, Zaveri got up twice to look at himself in the ambulance. He wanted to see the extent of damage and “perhaps decide whether to try live or not”. Even in the worst final hours, he was more amazed than wailing.

Abeer Khan, the director of How Do I Show The Ocean Space You Carried Inside You, does a sensitive job of capturing Kapadia’s personal loss as well as the damage and havoc of the incident. She recreates Zaveri in a montage of images, especially sketches drawn by Kapadia. The juxtaposition of zigzagging suburban locals adds another dimension to the narrative. The famed “lifeline” of the city is placed in perspective. Moving trains emerge as a metaphor for Mumbai’s vulnerability as well as its strength, moving on despite threats. A tour of city’s defining spaces—Carmichael Road, Malabar Hill, Sion Fort, Girgaum Chowpatty, Chor Bazaar, Goregaon Film City Road and Oval Maidan—position a personal tale on a broader, but familiar canvas.

Zaveri with long-time partner, visual artist Bharati Kapadia

Zaveri with long-time partner, visual artist Bharati Kapadia

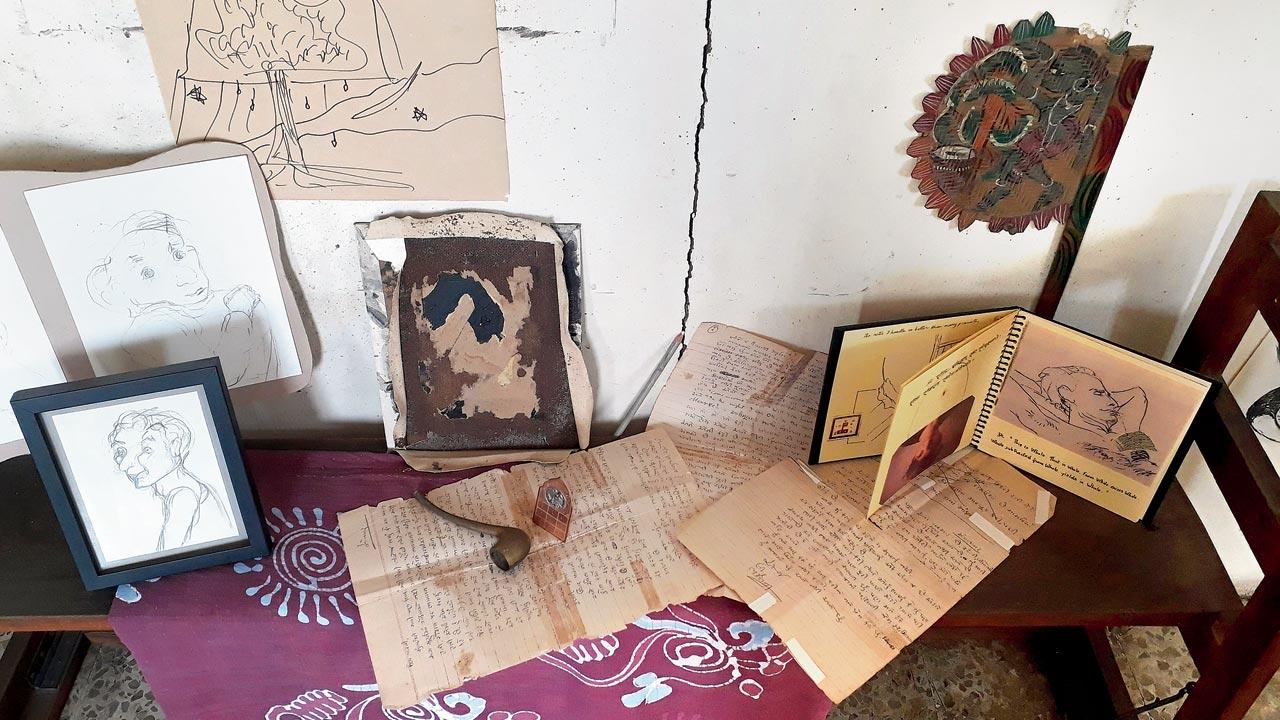

Despite the unfortunate end to Zaveri’s story, Khan’s movie doesn’t wear a sombre look. It celebrates the poet-playwright-theatre person-lover who achieved a lot in the limited years he lived. The lanky, broad-chested, perceptive, witty intellectual comes to life in vivid ways. Khan uses Kapadia’s personal memorabilia—Zaveri’s smoking pipe, the last handwritten letter, a trademark muffler, diary jottings, drawings, poems, gifts, a collage of old party photos—to resurrect a forgotten literary figure. The film has won appreciation and critical acclaim in art circles. Several cultural institutions in Mumbai as well as Baroda, Pune, Panaji and Ahmedabad are screening it.

Zaveri’s Gujarati poetry, evocatively voiced in the film by Ali Raza Namdar, provides a beautiful window to the writer’s understanding of the exigencies of life in a pollution-ridden harried Bombay. He imagines the monotony in the lives of his anagat pautro-prapautro (yet to be born grandchildren and great grandchildren) who, he says, will return home from work each day to be in front of remote controlled-TV/computer screens to watch vulgar films with expressionless faces. “They will yawn a few times, take a hormone injection, lie down in the bed, and in the blink of an eye, sink deep into a dreamless sleep.” Zaveri’s poems provoked enquiry into the human situation, just as his plays (35 one-acts and 20 full-length dramas) rebelled against social inequities.

Zaveri’s smoking pipe, the last handwritten letter, his trademark muffler, diary jottings, drawings, and poems are seen in the documentary

Zaveri’s smoking pipe, the last handwritten letter, his trademark muffler, diary jottings, drawings, and poems are seen in the documentary

In his last play Te Chhata (In Spite Of), Zaveri alludes to the Bhagalpur blindings, a series of incidents in 1979 and 1980 in Bhagalpur, Bihar, when the police blinded undertrials by pouring acid into their eyes. For him, theatre was a potent force of expression, a language in itself. And that’s why Zaveri’s practice was beyond languages. He directed plays from different languages and acted in over 50. He also produced five plays under the banner of Anaagat, a theatre production company founded by him. As Kapadia says in the film too, it was theatre that brought them closer. Zaveri mounted plays for different inter-collegiate contests, which included the activity in Sir JJ School, where Kapadia studied in the 1970s. Zaveri directed her in three plays.

Along with theatre, Zaveri lent himself to the other arts too. It showed in pursuits like newspaper column writing as well as screenplay and dialogue writing for Hindi films. The design studio, Art and Attitudes, which he launched with Kapadia in the Kala Ghoda precinct, took on production of art related books, catalogues and exhibitions, as well as art consultancy for collectors. Zaveri’s multi-faceted work is reflective of the creative decades (pre and post-Emergency) witnessed in Mumbai. His thoughts on art, freedom, life’s changing rhythms, cultural differences and celebration of diversity, speak so much of the chemistry of his times.

Abeer Khan

Abeer Khan

How Do I Show The Ocean Space You Carried Inside You is a teaser title. It unravels a single artist and his ideas. But it is also a tribute to artists who articulated the aspirations and angst of their times. There is another reason why the documentary evokes hope and solidarity. Two women artists of distinct generations—director Khan, 32, and Kapadia, 76, share a friendship and a belief in sharing Zaveri’s world view with a wider audience. “Me and Bharati started out as friends and then turned into collaborators. There was a certain level of comfort and closeness that the film demanded and for me, it wouldn’t have been possible if we started out as a mere professional crew,” says Khan.

Incidentally, Khan lost both her parents a little before she started shooting amid COVID-19 lockdown protocols. “I had not finished work on my father’s obituary when my mother passed away, in a span of five months. I had this film to complete, and I felt a sense of responsibility towards Bharati’s story. I gained strength from my parents who were artists.”

Grief is a personal experience that each journeys through in unique ways; often the grief caused by the loss of near ones saps people’s energy. Yet this film serves as a guiding light for those who are trying to come to terms with their loss.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!