Fifteen years after penning the celebrated bilingual text Singing Emptiness, Dr Linda Hess discusses why translating Kabir’s nirgun bhajans guarantees an intimate appointment with the inner self

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() Translation is not a full-and-final process, according to scholar Dr Linda Hess. “Readers will disagree with various aspects of my translation, and I urge everyone to do their own translations,” says the author of Singing Emptiness: Kumar Gandharva Performs The Poetry of Kabir, the bestseller bilingual text (Seagull Books, 2009), now being reprinted in a paperback avatar.

Translation is not a full-and-final process, according to scholar Dr Linda Hess. “Readers will disagree with various aspects of my translation, and I urge everyone to do their own translations,” says the author of Singing Emptiness: Kumar Gandharva Performs The Poetry of Kabir, the bestseller bilingual text (Seagull Books, 2009), now being reprinted in a paperback avatar.

It is a significant milestone in Hess’ Kabir journey, which started over 60 years ago, when the Fulbright scholar visited India. She taught English in Patna and travelled countrywide. It’s during this time that she got drawn towards the 15th century mystic poet Kabirdas, who became the principal subject of her doctoral thesis, as well as the first book The Bijak of Kabir in 1983. Today, at the ripe age of 80, she reiterates the artistic and spiritual value of translating Kabir’s poems/songs.

“It is a profound experience and brings one into intimate contact with poetry and music,” she vouches. For the last several years she has been working with Dr Jaroslav Strnad, a scholar living in Prague; together they are close to finishing the first of the two translation volumes of an early manuscript of Kabir, written between 1615 and 1621 in Rajasthan. The book comprises padas (song form), to be published in the Murty Classical Library of India series by the Harvard University Press. “The second volume should be the saakhis [aphorisms] and ramainis [a section of mixed-genre poems]. I’m not very sure that I’ll be able to finish that one, but hope so,” informs the religious studies scholar, who taught for two decades at Stanford University before her retirement in 2017. She currently lives in Berkeley.

This columnist is one of the many Linda Hess fans, eternally grateful, as an Indian, for her unique ability to connect the dots. In Singing Emptiness, Hess celebrates the connection between two Indian artistes, separated in time and space—Kabir (1398-1518), born in Uttar Pradesh, and a child prodigy singer Kumar Gandharva (1924-1992), born in Karnataka, who chose Madhya Pradesh (Dewas) as his residence for health reasons.

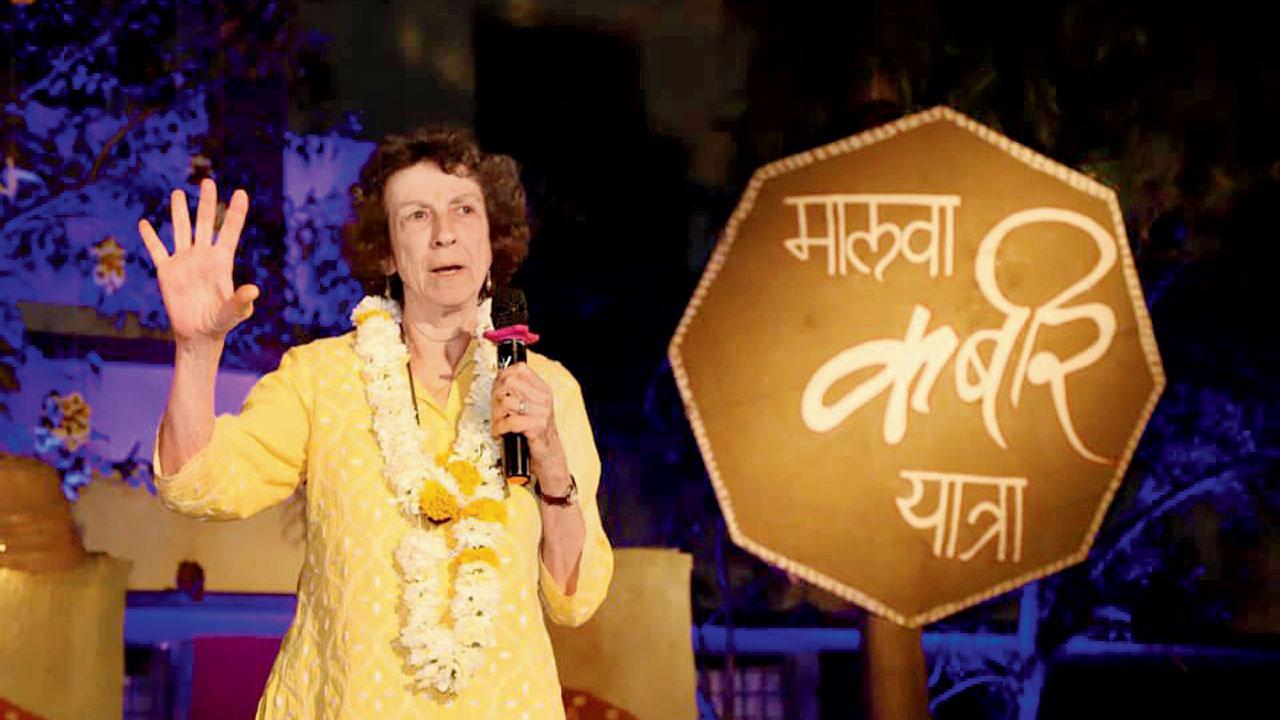

Octogenarian scholar Dr Linda Hess at the Malwa Kabir Yatra in 2020

In the classic Dheere Dheere Re Mana Kabir style, Hess devotes almost two decades to explore the oral and musical saint-poet, and likewise locate the nirgun formless space he inhabits. For a scholar who learnt Hindi language from scratch, and who (born in California, raised in a Jewish family) was not privy to innately Indian cultural constructs (Triveni Snan, Tap Tirath, Shrungi ki Mingi, Pind Brahmand) while growing up, the translations are indeed a model in cultural adaptation. Singing Emptiness forever raises the bar for translators who wish to take on tough ambitious projects in languages that they inherited with effort.

Hess, aware of her limitations in terms of language and classical music, says she was fortunate to be surrounded by friends (litterateur UR Ananthamurthy, singer Pralhad Tipaniya, critic Ashok Vajpayee, the Komakali family, which shared Kumarji’s private mehfil recordings) who encouraged her to render the English versions. The Kabir bhajans themselves were guiding lights.

Hess unmistakably catches the pulse of the shunya (emptiness) in which both Kabir and Kumarji flourished. This is no ordinary emptiness, but a rare union of the finite and the boundless. Kabir is alive to the splendor within the body which houses seven oceans and countless stars; but he views it ultimately as maati ka sakal pasara (the world is all but dust). Similarly, Kumarji was deeply invested in small wonders of grihasthashram—buying fresh bhindi, teaching children the finer points of gardening. But he also loved to visit the Shilnath Dhuni—fire first built by the Yogi sadhu who settled on the periphery of Dewas in 1901—where he discovered a Kabir pada embossed on the mirror shrine, “Ud Jayega Hans Akela, Jag Darshan Ka Mela”. Kumarji set it to an exquisite melody. His choice of the texts shows a pattern—he doesn’t sing the popular predictable Kabir couplets (Man ke jeete jeet hain/ Jako rakhe saaiyan), but he sings of subtler themes—the transiency of the Jhini Chadariya, the treacherous Maya Mahathagani, the cautionary Teeje Ban Pag Nahi Dharna, and the mysterious Shunya Gadh Shahar Shahar Ghar Basti.

At one point, Hess felt too inadequate to translate Shunya Gadh Shahar because the alignment of words defies logic. The text raised questions about what is shunya? Is it a void with negative connotations? But Kumarji’s song—his suggestive pauses, his phenk—clarifies the shunya space where anhad (the unstruck sound) resounds. A place to listen and sing.

It is pure coincidence that I chanced upon Linda Hess’ book Singing Emptiness at a time when “creative emptiness” was being discussed threadbare amongst a varied set of individuals gathered at the hilly Ranari village of Uttarakhand for a retreat hosted by the Krishnamurti Foundation India. There couldn’t have been a quieter setting—a hill overlooking the Bhagirathi river on one side and swaying wheat farms on the other—for a dialogue on the meaning of silence, renewal, and moment-to-moment mindfulness. It hinged on thinker-philosopher J Krishnamurti’s (1895-1986) idea of a retreat—a reflective space that allows a step back (leaving all beeping devices) from the routine. Scrapping the urban chaos and inherent tensions of city life, six individuals from diverse worlds grappled with silence in their own way. While some walked miles, some fasted, a few meditated in isolation.

My reading of Singing Emptiness ran parallel. It connected Kabir’s poetry with J Krishnamurti’s definition of silence: “Silence isn’t the space between two noises... isn’t the cessation of noise... isn’t something that thought has created. It comes naturally, inevitably as you open, as you observe, as you examine, as you investigate.” The concept comes close to the Anhad Mein Rum Jaai state of mind described in the bhajan—Hum Pardesi Panchhi Baba. Most of Kabir’s nirgun (without an object of devotion) bhajans refer to the silent sound or a seeker of the sound—naam, shabda, anhad naad, suno bhai sadho, avadhuta.

As Hess’ book narrates, Kumarji composed Sunta Hain Guru Gyani, after closely observing a ghumakkad yogi who sang door-to-door for his bhiksha. The yogi was not a great singer, but Kumarji admired the nirguni voice which had an amazing quality of creating (emptiness)—a carefree, non-attached state, “a sense of aloneness”. It is the same aloneness inscribed on the gate of the retreat space in Ranari: “It’s beautiful to be alone. Alone does not mean to be lonely. It means the mind is not influenced and contaminated by society.”

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!