Gaurang Shah presents a tapestry collection inspired by Shrinathji, showcasing a rich array of handcrafted textiles and techniques from across India

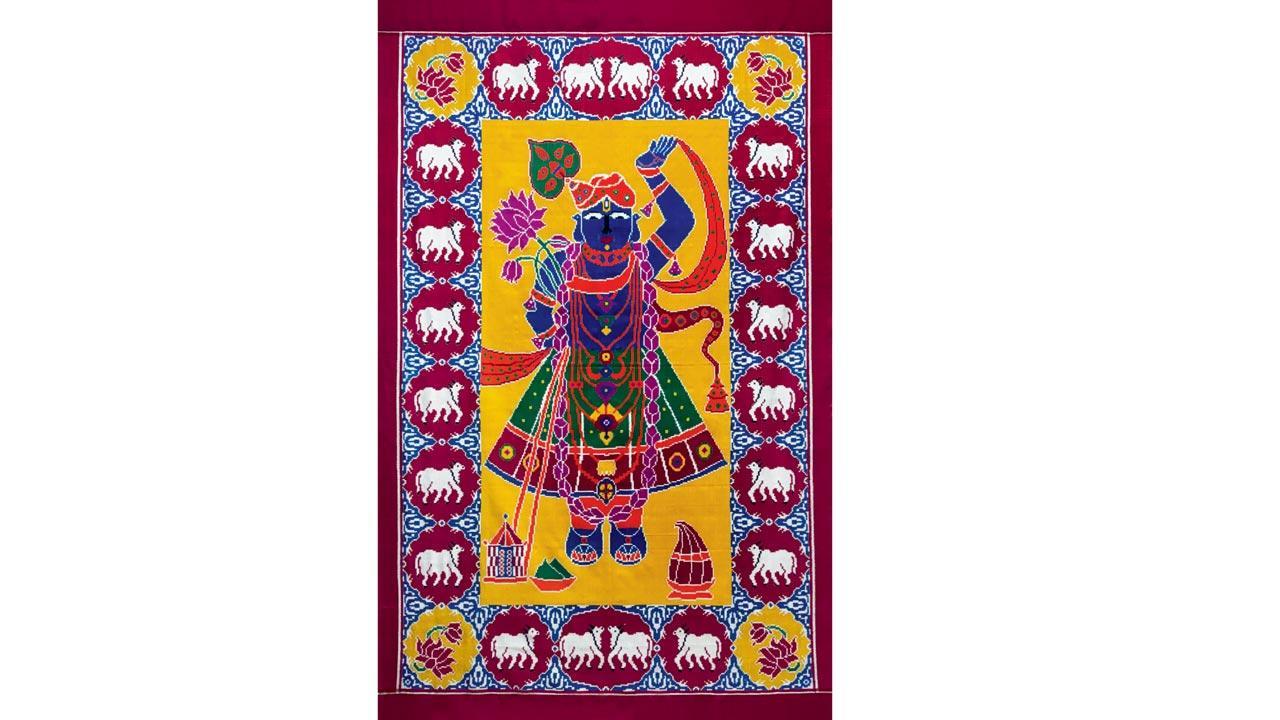

This 47 x 76-inch wall panel from Gaurang Shah’s Swaroop collection, crafted in Patan, Gujarat, required 360 days to complete. Using hand tie-dye and double ikat techniques in silk, the intricate process involves dyeing both the warp and weft threads before weaving, resulting in beautiful patterns visible on both sides—demonstrating the skill and precision of this challenging textile art

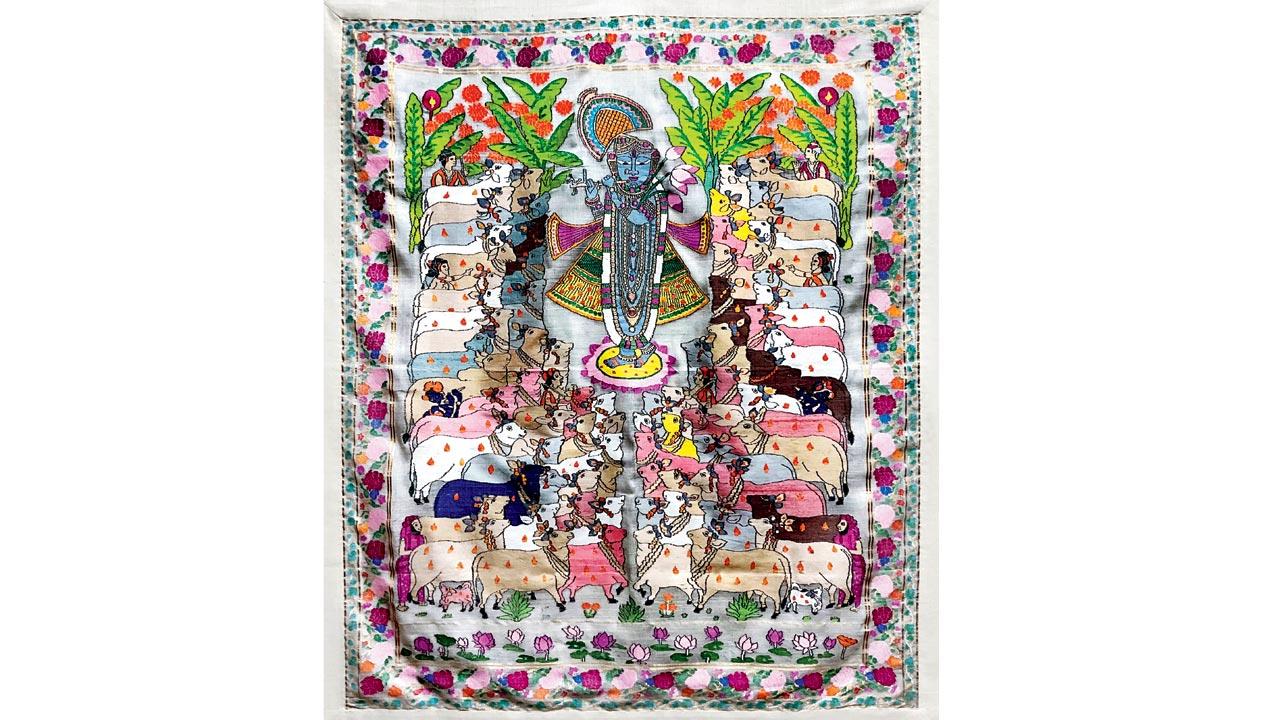

Shrinathji stands with a fully-bloomed lotus next to his left arm, surrounded by buds. His calm, steady gaze watches over a lively chorus of cows. The simplicity of expressions transports you to the bucolic scenes of medieval temple art. Yet, it’s not just the faces or the spiritual quality of Gaurang Shah’s wall panels that captivate—it’s how he brings the high-chrome, opulent robes to life.

Shrinathji stands with a fully-bloomed lotus next to his left arm, surrounded by buds. His calm, steady gaze watches over a lively chorus of cows. The simplicity of expressions transports you to the bucolic scenes of medieval temple art. Yet, it’s not just the faces or the spiritual quality of Gaurang Shah’s wall panels that captivate—it’s how he brings the high-chrome, opulent robes to life.

ADVERTISEMENT

The softness and mobility of cloth have been imitated on the jamdani loom in Swaroop, a 24-piece textile and handicraft tapestry series. Geometric patterns from Srikakulam shape a divine silhouette, while the soft weave from Venkatagiri adds serenity, and bold motifs from Srinagar amplify Shrinathji’s grandeur.

This Shrinathji wall panel (58 x 47 inches), crafted from hand-embroidered beadwork on raw silk, took 65 days to create in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

This Shrinathji wall panel (58 x 47 inches), crafted from hand-embroidered beadwork on raw silk, took 65 days to create in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh

Every tweak, rumple, and rustle is crafted with hypnotic effect using chikan from Lucknow, hand tie-dye and double ikat from Patan, gota patti from Jaipur, and aari embroidery from Kashmir, Dehradun, Hyderabad and Dhaka. The panels integrate traditional Indian painting styles, each with its own distinct history. Orissa’s storytelling through visuals, Pattachitra, narrative Kalamkari from Tirupati, opulent Tanjore paintings from Tamil Nadu, and folk Cheriyal scrolls of Hyderabad are meticulously recreated on fabric.

Swaroop debuted in late August in Hyderabad and 15 pieces will be showcased at Mumbai’s Taj Palace on October 18 and 19 as part of Shah’s exhibition featuring handwoven sarees and ghagras. “My first love is sarees,” Shah shares. “The six meters of canvas offer unique versatility for endless creativity, especially with intricate jamdani. You just can’t achieve that same design depth in a ghagra!”

Textile artist Gaurang Shah shares a light moment with weavers at one of his jamdani units in Alikam village, Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh

Textile artist Gaurang Shah shares a light moment with weavers at one of his jamdani units in Alikam village, Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh

The Shrinathji collection builds on Shah’s 2020 showcase of 37 Khadi jamdani sarees, each featuring handwoven pallus that recreated paintings by celebrated artist Raja Ravi Varma. These sarees were part of Khadi: A Canvas, a project co-curated by Lavina Baldota. “I need more challenges,” says Shah. “I want to be known for more than sarees and to explore different mediums using textiles.” Shah, who launched Gaurang’s Kitchen in Hyderabad in 2022, now ventures into home décor and interior design with Gaurang Home.

Swaroop was conceived after a friend’s suggestion to reinterpret Shrinathji—traditionally hand-painted by Rajasthan’s Nathdwara artists—across various textile and handicraft forms. So far, 12 out of 24 pieces have been sold.

Don’t be fooled by her smile. Lakshmamma means business when supervising the weavers alongside her husband, Annaji Rao, at Gaurang Shah’s looms in Srikakulam district

Don’t be fooled by her smile. Lakshmamma means business when supervising the weavers alongside her husband, Annaji Rao, at Gaurang Shah’s looms in Srikakulam district

Shah views Swaroop as a significant shift from his Ravi Varma project, which centred on Khadi jamdani and natural dyes. “Swaroop allowed me to explore Shrinathji through 24 diverse weaving and handicraft techniques of India,” he says, with plans to further develop his textile art series with Ganeshji next year.

To understand the essence of Shah’s work—he prefers the term “artist” over “designer”—one need only visit his jamdani units in Srikakulam, India’s oldest Gandhian weaving district in Andhra Pradesh, and his design studio in Hyderabad. There, the 2019 National Film Award winner for Costume Design for Mahanati is often seen in a uniform of navy or dark green linen shirts, Marks & Spencer or Brooks Brothers trousers, and crocodile-ostrich skin shoes. He embodies a shape-shifting relationship with handlooms, leveraging them to explore contemporary themes resonating with heritage.

This handwoven jamdani panel (41 x 50 inches) was crafted in Srikakulam over 90 days using Khadi yarn. Known for its intricate patterns and lightness, the jamdani technique uses a supplementary weft, where additional threads are woven into the base fabric to create motifs

This handwoven jamdani panel (41 x 50 inches) was crafted in Srikakulam over 90 days using Khadi yarn. Known for its intricate patterns and lightness, the jamdani technique uses a supplementary weft, where additional threads are woven into the base fabric to create motifs

“Back in 2003, the roads to Srikakulam were hardly passable,” he recalls, effortlessly switching between Telugu with the weavers, and English (with a smattering of Hindi) for the media. “A couple of families practiced Khadi jamdani saree weaving with simple booti [small motifs scattered across the fabric], but their work wasn’t enough for them to thrive.”

What began as a small initiative with master craftsman Annaji Rao and a few looms has expanded to 120, training over 300 women weavers, many of whom were once vegetable vendors. These artisans, now masters of jamdani Paithanis, have contributed to the recreation of Ravi Varma sarees. By modernising the designs and transforming them into luxury products, Shah has introduced experimentation within traditional techniques, ensuring consistent work and a sustainable income for weavers, who now earn between Rs 14,000 and Rs 20,000 per month. “This approach also secures the viability of my business,” Shah admits.

What do you aspire to create that will endure beyond your time?

Gaurang Shah: Everything I know about textiles comes from self-education; I am not from a design school. It is my passion, my fire. While designers launch one collection every six months, I create a new one every day!

When I began working with weavers in 1999-2000, handloom was struggling for creativity. I showed them that innovation was possible by using traditional techniques to create contemporary products—a fusion, so to speak. Today, we collaborate with over 7,000 artists across 16-17 states in India.

Every region of India offers unique textiles and crafts, each with distinct designs, colours and textures. In contrast, countries like Cambodia, Thailand, and Uzbekistan focus mainly on ikat. While Europe offers only a limited selection of embroidery styles, America has virtually none. China relies on machine production, and even Japan, known for indigo and shibori, sources jamdanis and Khadi from India. Yet, many design students today prefer to copy the West, favouring gowns with net embroidery over handcraft.

The industry is driven by cheap, low quality production. While many top designers talk about sustainability, few are genuinely committed to preserving handloom artistry, which requires patience and precision.

Too often, those with lesser-quality creations are the loudest, while our behind-the-scenes efforts speak for themselves. Ultimately, I want to leave a legacy that celebrates our diverse textile heritage—the world’s first wonder.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!