In a new book, geographers, archaeologists and maritime historians celebrate ports, docks, forts and harbours which made Mumbai an international centre of trade and industry

History stands still at the Ferry Wharf: Bhaucha Dhakka caught in a yesteryear frame

![]() Ruined forts can hold captivating chapters of history which throw light on the past. The ruins also underscore the shifting priorities of political powers. The Vasai Fort built in 1533 as a symbol of opulence and maritime supremacy of the Portuguese over the Mughals, lost its centrality (1739) during the Maratha rule; the fort was later taken over by the British East India company. In 1909, it was declared a protected monument. After years of neglect, especially since the dilapidated monument became a trespassers’ refuge, the fort fell in the custody of the Archaeological Survey of India. Today, the fort is one of the landmark precincts on the bucket list of heritage lovers of Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Interestingly, the state forest department recently trapped a leopard near the Vasai Fort entrance. The big cat’s chase again underlined the fort’s desolation. Vasai definitely is nowhere close to Dom Bacaim (the city of lords) as it was, modelled after the Evora city in Portugal, which was home to the Portuguese nobility residing in huge mansions.

Ruined forts can hold captivating chapters of history which throw light on the past. The ruins also underscore the shifting priorities of political powers. The Vasai Fort built in 1533 as a symbol of opulence and maritime supremacy of the Portuguese over the Mughals, lost its centrality (1739) during the Maratha rule; the fort was later taken over by the British East India company. In 1909, it was declared a protected monument. After years of neglect, especially since the dilapidated monument became a trespassers’ refuge, the fort fell in the custody of the Archaeological Survey of India. Today, the fort is one of the landmark precincts on the bucket list of heritage lovers of Mumbai Metropolitan Region. Interestingly, the state forest department recently trapped a leopard near the Vasai Fort entrance. The big cat’s chase again underlined the fort’s desolation. Vasai definitely is nowhere close to Dom Bacaim (the city of lords) as it was, modelled after the Evora city in Portugal, which was home to the Portuguese nobility residing in huge mansions.

The Portuguese settlement in Vasai, at one point, was characterised by spacious streets, squares and a fortification equipped with 11-arrow-tipped bastions that was pierced on the land and creek side; the naval armada in the Vasai creek was kept in battle-ready position as Vasai was the capital of the Province of the North.

Current-day Vasai is in the news for the wrong reasons. It is a part of the burgeoning Vasai-Virar Municipal Corporation with an appropriate population of over 20 lakh residents. Its share of water woes, power cuts, rail route dependency, flooding sagas, rampant building construction and congestion provide fodder for the civic reporter’s daily dispatch.

A plaque memorialises Bhau: Mumbai remembers Lakshman Harishchandrajee Ajinkya (1789-1858) alias ‘Bhau’ who was the first local (belonging to the Pathare Prabhu community) to construct Mumbai’s first wet dock in 1841 for the convenience of the passengers and incoming ships to load, berth and embark.

A plaque memorialises Bhau: Mumbai remembers Lakshman Harishchandrajee Ajinkya (1789-1858) alias ‘Bhau’ who was the first local (belonging to the Pathare Prabhu community) to construct Mumbai’s first wet dock in 1841 for the convenience of the passengers and incoming ships to load, berth and embark.

Like Vasai, numerous docks, ports, yards, naval bases, creeks—past their prime glory—have been showcased by the Maritime Mumbai Museum Society in a new volume titled Gateways to the Sea. Covering the rich ecosystem of historic ports and docks on the Western littoral, the newly released book reminds the reader of the vast constituent neighbourhood that contributed to the making of the eminent fabled city of dreams, a sprawling megalopolis and an international trade and industry centre! The volume celebrates the creeks and estuaries that have remained submerged under the meta narrative of Bombay. In her preface, Dr Shefali Shah calls them “backwaters of history” which deserve to be revisited. The book offers a roll-on-roll-off ferry ride to the forgotten corners.

“We know that history is presented selectively. Often, Mumbai’s history remains limited to the famed island city, with a conscious-unconscious emphasis on the South of Mumbai. The narrative of economic rise overpowers the narrative of Mumbai’s emergence as a port city for two millennia. The MMMS wishes to bring out the lesser-celebrated precincts,” says society Vice-President Anita Yewale. She is one of the editors of the book, which is designed for readers beyond maritime history circles.

Aerial view of the Alexandra Dock and the Hughes Dry Dock

Aerial view of the Alexandra Dock and the Hughes Dry Dock

The new volume straddles multiple academic disciplines to underscore the significance of an ecosystem. Chapters focus on architecture (The Architect of Bhaucha Dhakka—The Ferry Wharf of Mumbai), history (Thana: Tides of History), archaeology (The Mandad Excavations/Discovery of the Pre-Roman Port Site of Mandagora), maritime strategic defence (Janjira and Rajapuri Forts: Connected Histories in a Coastal Complex) and historiography ( Chronicles of Chaul).

Each chapter dwells on a micro-study done by a subject expert—For instance, former Vice Admiral IC Rao (known as the “Save Vikrant” advocate) writes on the Sassoon Dock. Rice, Salt and Cartwheels: The Story of Panvel Bunder is penned by Dr Smita Dalvi known for the book Panvel: Great City, Fading Heritage. Similarly, archaeologist Dr Suraj Pandit, faculty at Sathaye College, sheds light on Sopara: A Sacred Port City in the new volume. He has written on the same subject in his book Mumbai Beyond Bombay, as well as in Neera Adarkar’s collectors’ volume Multiplicities. In that context, Gateways to the Sea is a fresh addition to the existing body of work on the larger urban-modern vision of the Mumbai metropolitan region which predates Mumbai.

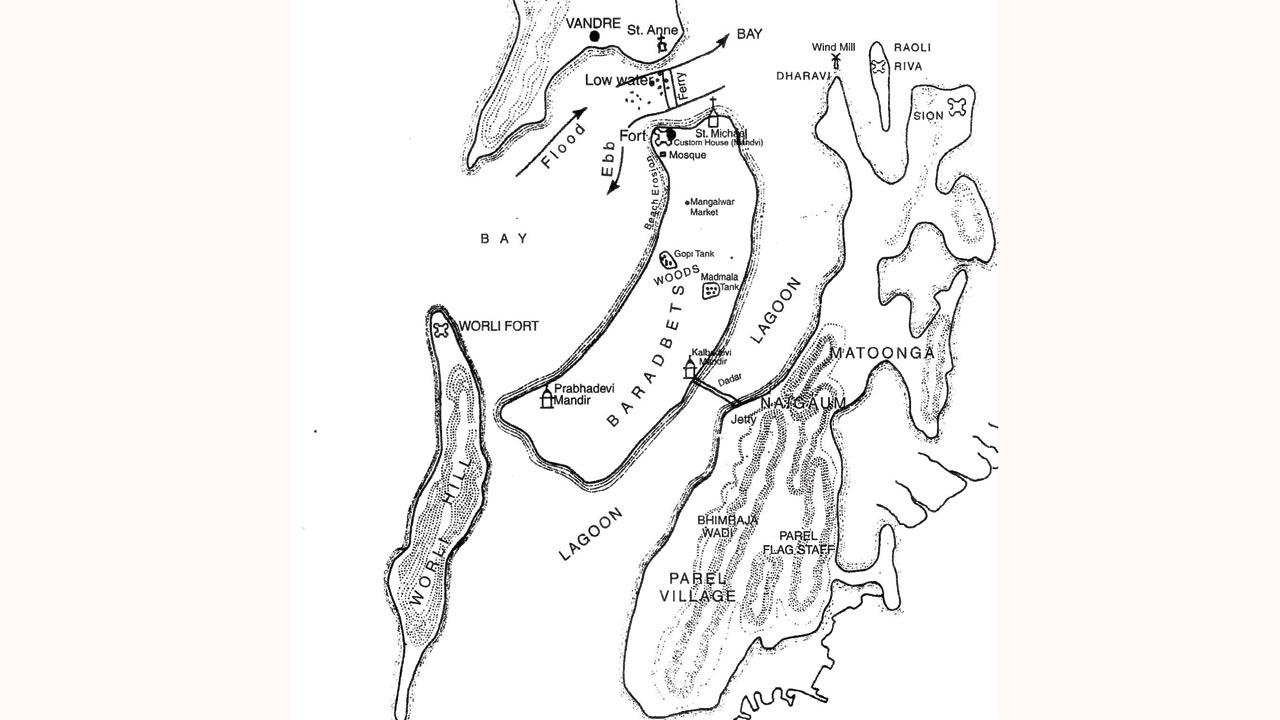

Mapping Mahim of the Past: A map shows the pre-Mahim causeway archipelago of seven islands: Bombaim, Parel, Mazgaon, Mahim, Colaba, Worli and Old Woman’s Island. Kolis were among the first inhabitants who navigated between these islands separated by lagoons.

Mapping Mahim of the Past: A map shows the pre-Mahim causeway archipelago of seven islands: Bombaim, Parel, Mazgaon, Mahim, Colaba, Worli and Old Woman’s Island. Kolis were among the first inhabitants who navigated between these islands separated by lagoons.

Geographically speaking, the book offers a north to south linearity, starting from four coasts on the North; then East of Mumbai, covering inland ports to the north and east of the city, as well as the Jawaharlal Nehru Port across the harbour on the mainland. The last segment delves into South of Mumbai, along the west coast of mainland Maharashtra.

Gateways to the Sea places the ports and docks in the overall history of political expansion, settlement and infrastructural development. For instance, the port city of Sopara (with the iconic Buddhist monastery) was the end point of caravan routes from Ujjain that converged with sea routes for Roman trade. Sopara is listed in periplus (log book of Greek navigators) as one of the major market-towns like Kalyan. Many references to sea voyages, naval battles and deep-sea travels to Sopara and Vasai can be seen in Portuguese correspondence.

Ruins of the Vasai fort

Ruins of the Vasai fort

Like Sopara, Panvel too, rose to prominence over the centuries, as a centre of sea trade. It was also a nucleus for revenue collections, a significant portion of which were port duties. It was under the Gujarat sultanate in the 15th century as Panwelly; the hill forts of Karnala and Sankshi guarded the land routes to the Deccan. After the Portuguese gained control over the north Konkan coast by the mid-16th century, Panvel tilted towards the new power structure. The Portuguese built the Forte da Belaflor do Sabio (Belapur fortification near the port) at the mouth of the Panvel creek.

Later, the fortress at Belapur witnessed many battles between the Portuguese and the Marathas.

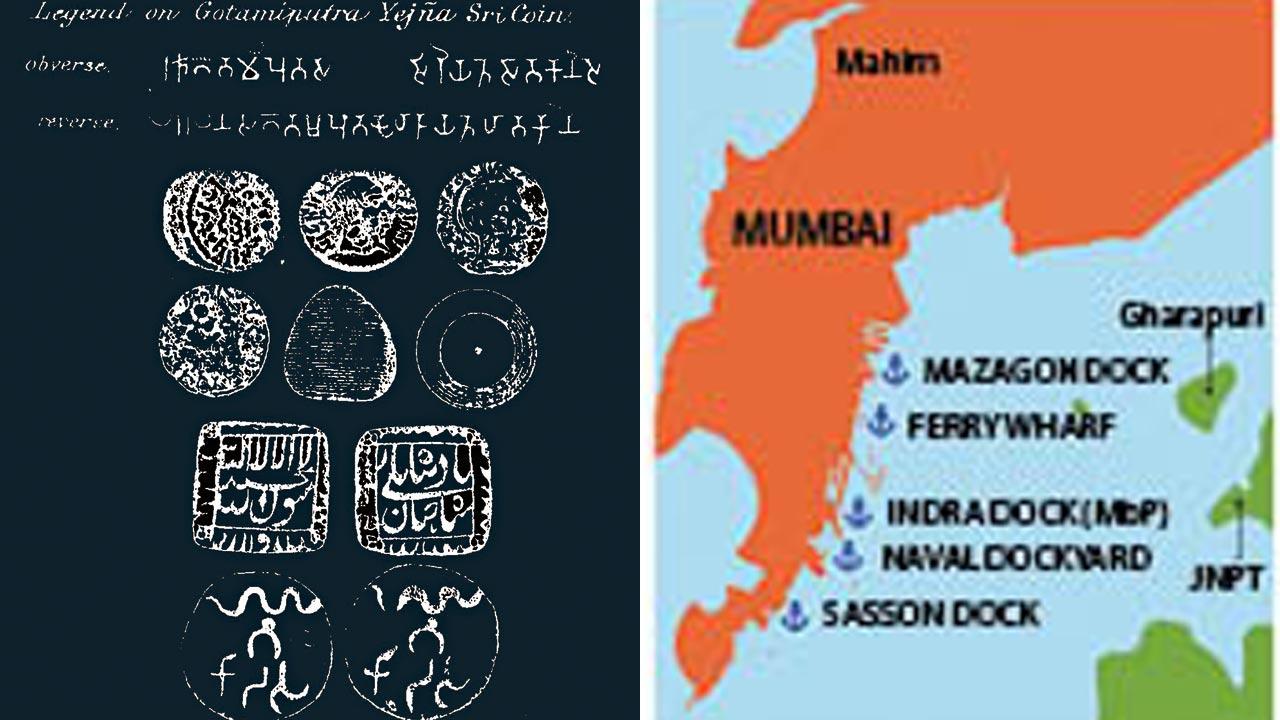

Lost Treasures of Sopara: Coin inscriptions show the impact of the Satavahana rulers whose seat of power was Sopara (Shurparaka), the city of braves; (right) Docks of Mumbai. Pics Courtesy/Maritime Mumbai Museum Society, publications division of Information & Broadcasting Ministry

Lost Treasures of Sopara: Coin inscriptions show the impact of the Satavahana rulers whose seat of power was Sopara (Shurparaka), the city of braves; (right) Docks of Mumbai. Pics Courtesy/Maritime Mumbai Museum Society, publications division of Information & Broadcasting Ministry

Gateways to the Seas not just underlines the interconnectedness of trade and transport, but also links political conquests with multi-hued settlements, new lifestyles and an openness to life. This columnist, a resident of Mahim, swells with pride while reading about the multilayered multicultural past of the area—the curvilinear island of sand (Baradbet) once was a home to fisherfolk Kolis; but also embraced (1140 onwards) by other communities from the time of Raja Bimb. The king granted rent-free land to Pathare Prabhus, Panchals, Vadvals, Kunbis etc—Agris, Bhandaris, Katkaris too immigrated soon. While Agris manufactured salt, Bhandaris tapped toddy. Mahim was a major liquor centre; Christians, Parsis and Bhandari Hindus were the drivers of the distillery commerce. It also witnessed large-scale influx of Muslims (Arabs, Memons, Khojas, Bohras) in the early 15th century; just as it saw a wave of European immigrants after the Portuguese took over in 1534. When the British took over Bombay, the Portuguese let go of Mahim only after two decades of fighting for the precious link to the Salsette!

Today, Mahim is another bustling suburb with no harbour site; the river flowing through it has long dried. The glorious multicultural past of Mahim, however, reflects in one aspect—Mahim houses three distinct iconic places of worship within one kilometre on the Lady Jamshedji Road—Sitaladevi temple, Shaikh Makhdoom Ali Mahimi dargah and the St Michael church. Living in proximity to those three spots means residing near significant pages of history.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!