Over the next three years, Darjeeling-based Salil Mukhia will travel across Nepal, Bhutan, Burma and other Southeast Asian countries to document some of the last stories and tribal folklore of critically endangered cultures. The project, Stories On The Verge, could well be the last word in oral storytelling in the region, finds Kareena Gianani

For the past three months, a new rhythm runs through the days of Kwoico Salil Mukhia’s life in Kathmandu, Nepal. The 35-year-old, who founded Acoustic Traditional, an organisation which promotes oral storytelling and tribal folklore, spends all his time meeting NGOs and historians who work with Nepal’s indigenous tribes, drawing up meticulous maps of remote, hilly regions and having long chats with locals over tea.

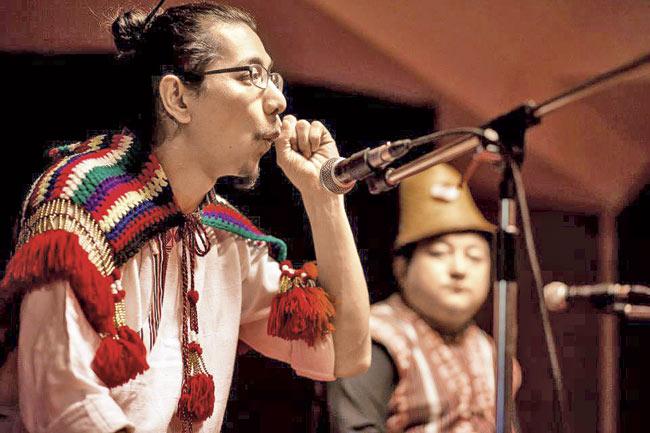

Acoustic Traditional’s founder, Kwoico Salil Mukhia

On May 1, Mukhia launched the project, Stories On The Verge, which looks at “recording and retelling some of the last stories and storytellers of critically endangered cultures in Asia, with a specific focus on Eastern Himalayas”.

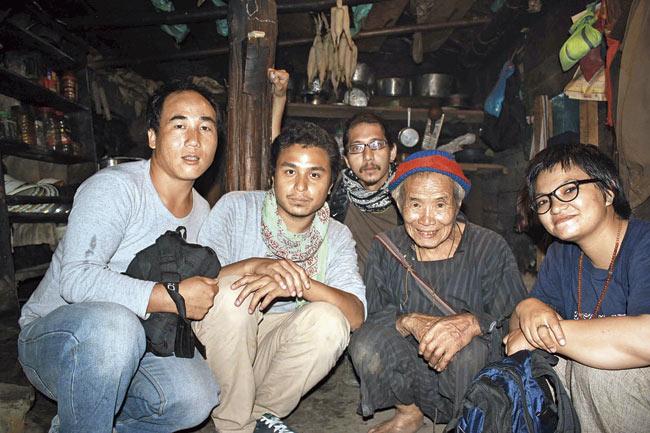

His team with Merek Lepcha (second from right), the oldest shaman in upper Dzongu, Sikkim. Pics/Kwoico Salil Mukhia

Over the next three and a half years, Mukhia will travel across Nepal, North-East India, Bhutan, Burma, rainforests of Asia and other Southeast Asian countries, where he will organise storytelling sessions and help the project culminate in a feature film on the communities.

Acoustic Traditional is working with NGO Nirbhaya Manch and the National Foundation for Development of Indigenous Nationalities in Nepal. However, for the project to achieve the unprecedented, Mukhia must fight against time.

“In most cases, merely 80-200 members of these critically endangered tribes remain, which means that we must reach them before their last storytellers pass away. Moreover, we don’t want these stories to simply end up in our Indian archives, so we will disseminate these tales on the way through storytelling sessions and workshops.”

Tale of two stories

Stories On The Verge is inspired by two incidents in Mukhia’s life which haunt him till date. Three years ago, Mukhia heard of the death of one of the last shamans in Sikkim.

He was the sole practitioner of an 800-year-old tradition of rituals of the Lepcha community, and the only one who knew a specific form of rites to worship Mount Kanchendzonga.

“We had begun documenting that ritual a few days before he passed away and had a long way to go. Now, his tradition, those stories and the ritual is lost forever,” says Mukhia regretfully.

Soon after, another shaman, who was believed to be the guardian of Eastern Sikkim and was the last worshipper of the river Teesta, passed away before Mukhia and his team could document his stories.

“I knew then, that if I have to do anything worthwhile to preserve tribal storytelling, it has to be done fast,” says Mukhia. He decided to start in Kathmandu, where he was a music teacher in his 20s.

“If you’re doing anything related to Himalayan cultures, Kathmandu is the place to begin. Our cultures are porous and juxtaposing our ancient stories throws up startling similarities in nature and form,” he adds.

In Nepal, Mukhia will kickstart the documentation process with the Raute community. Only 1,000 members remain of this nomadic tribe and the population is scattered in Nepal’s remotest regions.

Over June, Mukhia will travel to Mustang district, where the Rautes are believed to reside. Next, he will document the stories of the Kiranti group of tribal communities who have a distinct tradition of oral storytelling.

“The Kiranti group has many a Naso (storyteller), both men and women, who may be shamans, too. They have a robust tradition wherein Nasos relate the Mundum, which are their scared verses, much like the Vedas in Hinduism.

The Mundum are not religious – they focus on how life must be lived. They have never been written down, so I hope to reach out to the Nasos and preserve this oral tradition,” says Mukhia.

Return to the roots

For Mukhia, Stories On The Verge is as much about finding his own roots as it is about documenting endangered cultures. As a child, Mukhia heard folklore of his community, Kwoico, from his grandfather, who was a Naso. “His fables were delightful, but did not include many myths, such as my community’s version of the myth of creation.

When I began travelling across India for Acoustic Traditional’s sessions, I realised that most other Himalayan tribes had their myth-of-creation stories intact. Nepal, like India, has members of my tribe, and I plan to meet storytellers and Kwoico myths.

Along the way, Mukhia is prepared for an arduous time. Stories On The Verge is largely self-funded, and Mukhia is now looking at crowdfunding. Secondly, as he moves into remote areas of Nepal, and other Southeast Asian countries later, common, dominant languages will be of no help. “It is a struggle to find translators, and those who speak different dialects of that language, more so,” he explains.

The essence of stories also lies in their non-verbal aspects, which will be Mukhia’s biggest challenge. “That’s the reason I want to record these stories, not just write them down. Many stories I will come across will be rooted in rites and rituals, and that cannot be translated accurately.”

Mukhia takes much solace in the fact that we are all connected by stories, and that will aid support and understanding on the way. “All stories, for instance, are rooted in nature. Its role in our psyche, in our spirituality is always implied. Our stories indicate that we are interrelated, and I never forget that,” smiles Mukhia.

Log on to www.facebook.com/acoustictraditional.org to fund the project, or email salilmukhia@gmail.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!