Few years before mid-day was born, the idea for a new state capital was killed. Civil engineer Shirish Patel, who co-conceived Navi Mumbai with Charles Correa, looks back at the ambitious plan

CBD Belapur, where the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporationu00e2u0080u0099s office stands, was envisioned as a hub for offices. Pics/Sameer Markande

What kind of city do we want? In those years, actually, the question was: What kind of India do we want?” says Shirish Patel.

ADVERTISEMENT

There is a well-worn tale, and its varying versions, among architects, civil engineers, urbanists and government bodies, of how Navi Mumbai was born. It was the mid-1960s. The Maharashtra government was nudged to look eastwards from Bombay, to the districts of Thane and Raigad. Industries had started coming up in the Thane-Belapur belt; work on the first bridge, now called the Old Vashi Bridge, to connect the island city to the eastern mainland, had begun. Bombay had started to sag under the weight of its own glory — its population count going up and quality of life dipping.

Shirish Patel at his Carmichael Road home in South Mumbai. Pic/Bipin Kokate

A holy trinity — chief architect Charles Correa, architect Pravina Mehta and civil engineer Patel — wrote a piece titled ‘Bombay: Planning and Dreaming’ in the June 1965 volume of Marg magazine. It was a response to BMC’s Development Plan 1964. The trio spoke of a “twin city”, not one that lived for the sake of the megapolis, but an independent parallel entity.

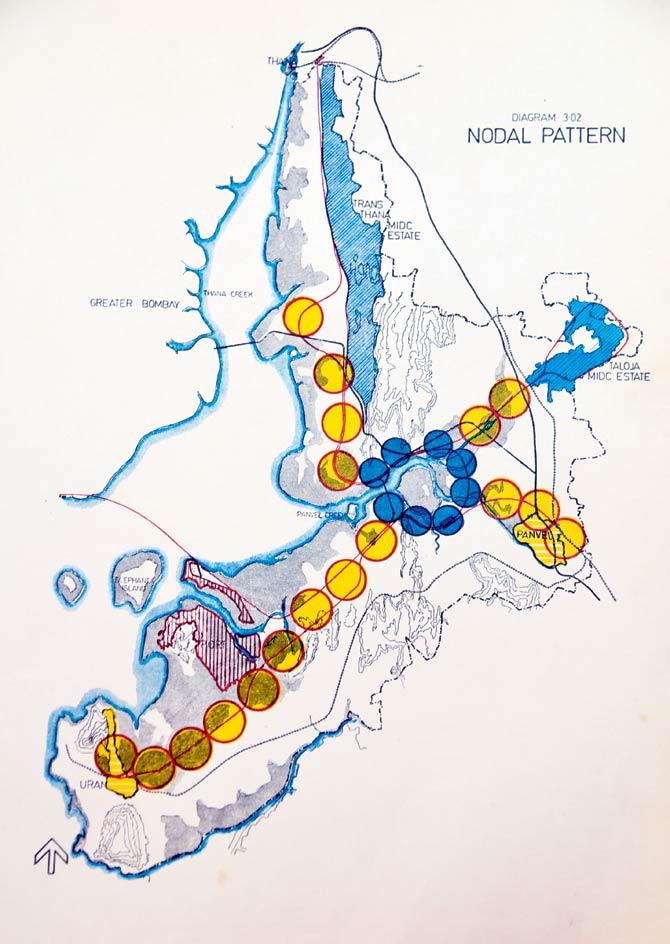

The distribution of nodes in the original plan for Navi Mumbai, as conceived by Charles Correa, Pravina Mehta and Shirish Patel

“That’s how it started,” says Patel. “We suggested that the government acquire area to the east of Mumbai, on the mainland, and plan a new city. We also strongly recommended for the headquarters of the state government to move from Nariman Point to Navi Mumbai.”

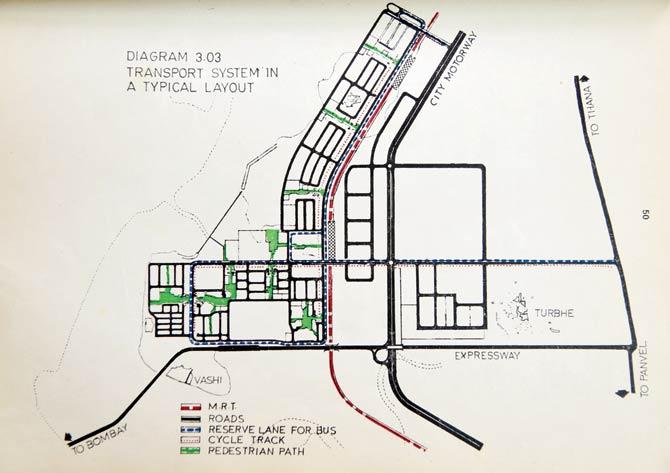

The layout for the transport system in each node included a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), which Patel says never got executed. Each BRT was meant to be a lane exclusively for buses from the railway station to residential areas. Pics/CIDCO

City from scratch

Rueing the manner in which Ulhasnagar has grown into an unplanned mess, he continues, “Navi Mumbai was a blank slate. We had all kinds of ideas. When we first saw it, it had a varied landscape. There were hills; there was the Panvel Creek, which we thought could be made into a lake by damming it; low-lying areas along the creek were obviously hard to develop.”

CIDCO, in CBD Belapur, where Patel held office as director of planning and works until 1975

Patel, now 84, is recuperating at his Peddar Road home from a recent illness. Correa and Mehta are no more. Patel has preserved the charm that agile visionaries tend to cultivate early. He evokes pictures in your mind, filling it with little details, teasing your imagination to pay attention. In that way, Patel, the civil engineer who gave India its first flyover, at Kemps Corner, is a blueprint artist.

With similar thought values, the three visionaries had set down two important features for Navi Mumbai. First, that sufficient land would be provided to all income categories, that affordable housing would be key. This city was for everyone. Second, Navi Mumbai would be self-financed from the sale of its land, and would provide for its own physical and social infrastructure.

When Patel dreams of Navi Mumbai, however, you are quickly recalled to reality. If you are a resident of Panvel, Kharghar or any part of Navi Mumbai, it is with mixed feelings that you go about your day. The wide roads, the orderly sectors, localities flanked by green hills are only offset by the difficulty of taking the stuffy Harbour Line.

There was a plan that only partially succeeded.

An 'Old Mumbai'?

We did it with the nation’s capital, then why not with the state’s? Half a century later, it is a question that still puzzles Patel. “We have successfully shifted capitals in the past, from Delhi to New Delhi for instance. Can you believe what it would have been like if the capital was in Old Delhi? Chaos,” he says.

The idea with shifting the capital to Navi Mumbai, along with affording bungalows for ministers, was to jump-start jobs in the area, so the new city could be more than a dormitory town. That way both the old city and the new could prosper, says Patel.

Five years down the line, in 1975, Patel, who helmed planning at CIDCO as director, along with the other two, hit the eject button. The seat of power squatted in the ‘old’ city, refusing to move. “The government was selling plots in Nariman Point simultaneously. How do you expect Navi Mumbai to grow if this was happening? What is the point of adding jobs to the tip of a city that you had to travel to every day?” says Patel. He then adds, “I am not in this line of work to prettify cities. I have to take overall strategies for planning into account.”

But Patel hazards a guess why the state government held fort in South Mumbai. There was “a real fear” that with moving capitals, Mumbai would become a union territory. As long as the capital was in Mumbai, “no one would dare take it”.

Since the plan to shift centres of power never came through, Navi Mumbai has lost out of its share of iconicity too. Where was the prestige it badly needed, after all, which was to be derived with the tag as state capital?

Today, its landmarks are private malls and structures built by private bodies, but public heritage is absent, save for the municipal corporation building.

But Patel, laughs lightly and admits that being in their early 30s (Mehta was a little older) had something to do with abandoning ship as well. “We were like ‘bachchas’, and the government didn’t take us seriously. In hindsight, I feel that if I had had a little more of the persistence of the kind that Madame Curie had, and if I had stuck on, it would have been frustrating, but a few of our ideas would have been implemented.”

In 1995, the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) had organised a seminar, 25 years after Navi Mumbai started taking shape.

Patel was interviewed in a paper and asked to rate Navi Mumbai, out of 10. Three, was his reply. “But [MV] Gore, from TISS, in a faint academic voice, said, that I was being unfair in giving it three. He said he would give it 4/10,” laughs Patel.

Somewhere in the course of our conversation, Patel says that he has heard many tell him that they love living in Navi Mumbai. “Whatever little success it has had is because it was planned.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!