With Irani cafés, iconic photo studios and indie bookstores admitting they will be forced to vacate if the new rent laws are enforced, are we staring in the face of an unrecognisable Bombay?

There's a reason that the city sheds tears when a Rhythm House or a Samovar shuts down. Or it rushes to get its last mawa cake when rumours of closure surround B Merwan. While we may love our Starbucks spiced latte, bun maska dipped in Irani chai, enjoyed over a book bought from Strand, is a comforting thought for both the body and soul. What, then, will happen when this becomes another memory relegated to nostalgia, sighed over during chatter at art exhibitions?

HIRALAL KASHIDAS BHAJIA: Gaurang Shah, the second-generation owner, says though his brother studied engineering and he did his BCom, both chose running the eatery over other careers. The Bhuleshwar landmark, which stands at the corner of Patel Road, turns 80 this year and is famous for its farsan and seasonal Gujarati undhiyu. Pic/Onkar Devlekar

With the state government proposing an amendment to the Maharashtra Rent Control Act, 1999 — aimed at residential and commercial tenants above 847 sq ft and 547 sq ft — rent across several Mumbai buildings controlled by the pagdi system will match market rates. Entrepreneurs behind much-loved institutions say they might be facing the noose.

ND MOOLLA AND sons: From stacks of sandalwood to metres of mulmul for sacred sudreh, Noshir Mulla’s Kalbadevi store houses religious article needed by Parsis. It’s a necessity store, that could soon become a relic if the Rent Act is amended. Pic/Bipin Kokate

A builders' Act

It should have been a day that Vimal Thakker didn't stop smiling. Some works by his father, JH Thakker, have been up on display at Byculla's Bhau Daji Lad museum as part of the ongoing exhibition Silver Magic. In fact, he has just received a text from the museum's director Tasneem Mehta about the positive response the show has got.

DAVID AND CO: The Dhobi Talao printer has since 1952 been a mecca for the Catholic community. Even today, the nearby St Xaviers’ College commissions all its printing orders to David. Founder Felix Dias says he started the company after paying a pagdi of Rs 65,000 and a rent of Rs 100. The rent is now Rs 2,500. Pic/Bipin Kokate

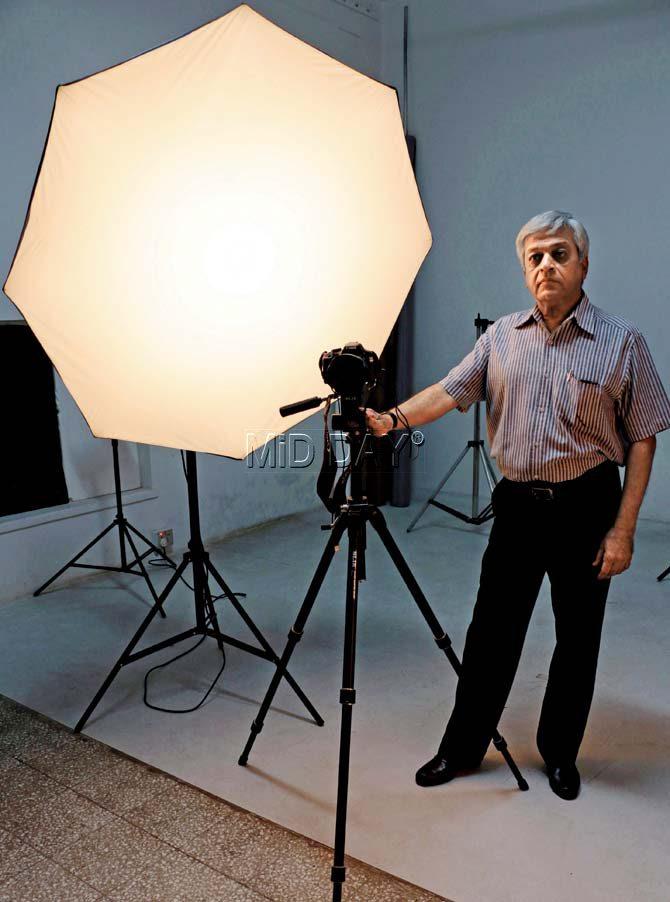

Vimal is the second-generation owner of India Photo Studio, an iconic institution that stands at Dadar TT Circle. Founded by his father JH Thakker in 1948, the 68-year old studio was once frequented by the stars. “Dilip Kumar, Meena Kumari and Nargis Dutt were regulars and my father would take up a lot of film publicity projects,” Vimal tells us.

india photo studio: Founded by JH Thakker in 1948, this 68-year old studio has shot Dilip Kumar, Meena Kumari and Nargis Dutt, says Thakker’s son Vimal. It’s one of few studios in the area that still survives. Pic/Swarali Ppurohit

But, the warmth of nostalgia is replaced by grimness. “It [the exhibition] is a matter of pride, but my mind is elsewhere,” he says. With the studio occupying around 1,400 sq ft space in Bombay Garage Building, a prime property in Dadar East, he knows that a monthly rent of Rs 10,000 is a sweet deal. “I understand that landlords feel they deserve more, but 200 times? People will file tooth and nail against it,” he adds.

Anand bhavan: While Madras Café and Rama Nayak in Matunga are safe, as the buildings are owned by the founders, Anand Bhavan at King’s Circle has been seeing a drop in customers over the years. Owner Haridas Nayak fears it won’t survive the new rent act. Pic/Phorum Dalal

He voices the most common angst — that the move is meant to change the face of Mumbai, replacing old buildings with highrises.

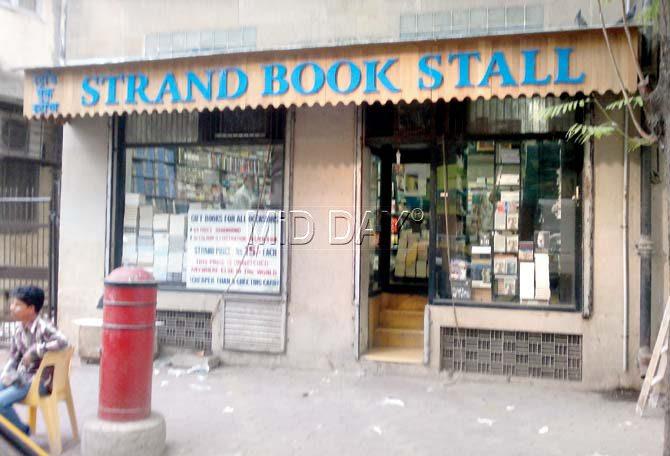

STRAND BOOK STALL: Vidya Virkar, owner of the iconic bookstore, says her father TN Shanbaug, knew that what worked in their favour was an affordable rent. If a new rent system comes in place, they would have to rework their financial model

“With the number of people living and working out of pagdi spaces, is it practical? Even if the current tenants, who cannot afford to pay, get out, who is going to rent these spaces at astronomical prices? Obviously the old buildings will be razed down.”

Chemould frames: Adil Gandhy says his grandfather once owned Princess Building, which houses Chemould Frames. However, the rents made from the tenants wasn’t profitable and his grandfather sold it since he “couldn’t keep addressing complaints from the tenants about water and electricity”. Pic/Bipin Kokate

Remu Javeri, owner of Touch of Joy, parlour at Apollo Bunder, agrees. “The pagdi system is a tripartite agreement. The government's job is to give us a roof over our heads, not remove it. Today, it seems the builder's lobby is in power and the simple tax payer has no rights.” The parlour, started by Javeri's wife is 27 years old. “We built it from scratch, from fittings to chairs to equipment. It is our baby. While I would accept a gradual rent hike, it is unfair to hike the rent to 200-500 times overnight. It will affect lakhs of people who are not privileged.”

Not for profit

And, not everyone who owns a commercial establishment in Mumbai is rich. Even if it is an Udipi restaurant. When we meet Haridas Nayak, the 62-year-old third-generation owner of Anand Bhavan at King's Circle, he ensures we have a look at his menu board. One plate idli for Rs 30, one plate masala dosa for R50. Onion uttapam, priced at Rs 52, is the costliest item on the menu.

“Do you think I make a profit at such rates? Five years ago, I had customers who ate here three times a day — breakfast, lunch and the evening snack. Some would even parcel dinner for their family. Today, those very customers come twice a day, and then to have a cutting chai. The only reason I survive is because I serve home food,” says Nayak, who feels the new rent act proposal is a political ploy.

“Congress did this a year ago, and now, BJP has picked it up again. No one will be ready for this. I pay R7,000 in rent. I cannot afford to pay in lakhs. Today, no student from UDCT (University Department of Chemical Technology) nearby frequents my restaurant. They have a cheaper mess on campus.”

Lokesh Gopal Shetty, who runs Janata on Pali Naka, Bandra, doesn't mince words. “We will be finished if the rents are increased,” he says.

Along with Yacht Restaurant & Permit Room, Janata is one of the few options in the suburbs where you can get value-for-money alcohol, thanks to the customers it was meant to serve. “When my father built it 60 years ago, Pali Hill was a forested area, with nothing but a few bungalows. We used to be the place for labourers to have a meal and drink,” he reminisces. While the relatively low price-points persist at the bar, the clientele has changed. These days, you have to hustle with the hipsters and yuppies to gain entry.

The formula for Janata, he says, lies in its frugality. “I don't believe in interiors. I give my customers basic hygienic amenities, but good food at reasonable rates.”

One big family

For Dilip Maheswari, who runs an imitation jewellery business in Bhuleswar, coming to Hiralal Kashidas Bhajia for his morning, noon and evening snacks is a ritual inherited from his father. “My father used to bring me here, and for the past 30 years, we have been savouring this food,” he says, comparing the present state government with the British. “The British had the kala kayda (black rules). The present government is worse. It has joined hands with the builder nexus. These are iconic spots, and the city is about to lose its charm, and old family-run businesses,” he says, sitting in one of the chairs on the ground-floor establishment that stands at the corner of Patel Road.

In fact, Jhaveri Mahajan, the building that houses Hiralal Kashidas Bhajia has become a landmark. “The shop will turn 80 this year. This is our world. While my brother studied to be an engineer, and I did my BCom, we got into the business to carry the legacy forward. Is it fair that hawkers are allowed to take over footpaths and slum dwellers get homes, and we are thrown out?” says 60-year-old Gaurang Shah, one of those who protested at Wednesday's rally at Azad Maidan.

Go North?

A customer overhearing our conversation suggests that Shah move shop to a mall. “You will do phenomenally well.” While Shah doesn't react, it is not a thought that's escaped the owners of the city's landmark bookstore, Strand.

Stacked from floor to roof with books, this Fort shop hardly looks like a 800 sq ft space. The store, as its owner Vidya Virkar puts it, withstood “the global phenomenon of the challenging book business”, perhaps because although it remains a treasure chest of rare finds, it was opened with a business plan. “My father TN Shanbaug always emphasised that we were very fortunate to pay an affordable rent, which resulted in the discounts we were able to pass on to customers. The amendment to the Rent Act will hit where it hurts; an entire arithmetic based on low rent will be upturned.”

In the last few years, Strand has resisted the northward migration of establishments to Lower Parel, Bandra and Andheri. “We never considered relocating in some mall in Andheri, though proposals came often. It is true those areas have a younger population, which has both purchasing power and an interest in books. But, we would never be able to afford the rents proposed by a mall,” says Virkar. “We will need time to rework our financial model, which cannot be done overnight.”

And what of other bookstores in the area? Sterling Book House, when we speak with them, seem distressed. “Are you over 547 sq ft?” we ask them. We hear an instant sigh of relief.

“On what basis has the 547 sq ft cutoff been decided?” asks Adil Gandhy when we meet him at Chemould Frames, the 69-year-old Princess Street shop, his late gallerist father Kekoo Gandhy set up. The new Act will enforce the market-rate rentals on establishments that occupy an area of over 547 sq ft.

Gandhy points out that few would be able to afford such a set-up as his. “In Colaba, if you see, framers are in little spaces by the roadside,” says Gandhy, sibling to gallerist Shireen Gandhy. The space, which has relocated from an earlier location in the neighbourhood, hosted exhibitions by greats such as MF Husain.

Ironically, his family once owned Princess Building in which Chemould Frames now sits. They switched status when rents they made from tenants stopped being profitable. “My grandfather couldn't keep addressing the complaints from the tenants about water and electricity. Fed up, he sold it off.”

Communal loss

Besides favourite cafés and bookstores, there are communities that have been built around the over-547-sq-ft establishments that could suddenly face closure.

Close to Kyani & Co in Dhobi Talao, stands David and Co; which has, for the last 63 years, been the destination for most Catholics to get their cards printed for occasions, right from baptisms to weddings. Without blinking an eyelid, one look at the long shelves stacked with bride-and-groom cake toppers and invitation materials, tells you that the Rent Act could spell trouble for this place run by the Dias family. Felix Dias says he started the company in 1953 after paying a pagdi of Rs 65,000 and a rent of Rs 100. The rent has now escalated to Rs 2,500. “The rupee has lost its value and things have become expensive. Imagine, you have to pay a pagadi of that value today. It would almost be Rs 2 crore,” says Dias.

Adjacent to Seth Hormarjee Bomanjee Wadia Atash Behram at the turning of Princess Street, is Noshir Mulla's store that houses religious articles needed for Parsi rituals. From stacks of sandalwood to metres of sudreh, ND Molla and Sons is a necessity that could soon become a relic if the Rent Act is amended. Mulla, whose surname is spelt differently, thanks to a glitch in his birth certificate, is concerned by the possible hike. The shop is on land that belongs to the fire temple's trust, and Mulla shows carefully preserved rent receipts for two months dated 2014. The three-figured rent charged by the trust is countered by municipal taxes that are more than thrice the amount. “If the legislators think that an increase in statutory rent is smart, then can you imagine what will happen to the taxes?”

Will he cope with change? Mulla says he will pay his rent till he can, and when he can't, he shut shop. Interrupted by the constant trickle of Parsi customers, he says, “There is a Gujarati saying: There are only two things that cannot be predicted — the God of death, and a customer.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!