With Christie's set to auction a work by Adi Davierwalla, here's a closer look at the pioneering Modernist sculptor who found his calling in scrap wood and The Space Age

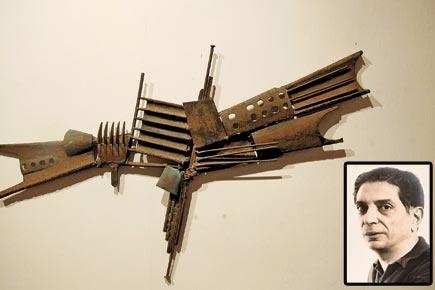

Adi Davierwalla with a sculpture he made during a fellowship at The Rockefeller Foundation in 1968. Pic Courtesy/Zarine Davierwalla

The fringe benefit of having a sculptor for a father, Zarine Davierwalla will tell you, is that when you ask him for something utilitarian, he'll probably gift you something fantastical too. As a 10-year-old, when she had asked for a study table lamp, her father, the late Modernist sculptor, Ardeshir Davierwalla fashioned an assemblage of metallic rods and blue marbles, evoking at once a starburst and primitive drawings. Only, Zarine says chidingly, it wasn't a table lamp, as she had requested, but one that had to be mounted on a wall. "Once I saw it, I knew I couldn't keep it all for myself," laughs Zarine, now 62.

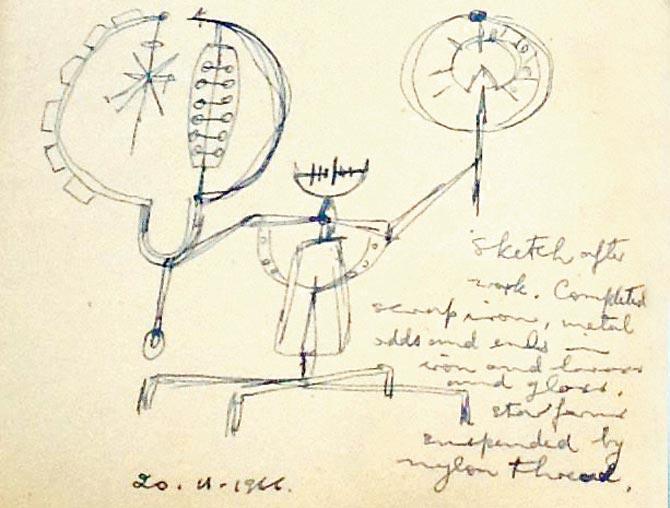

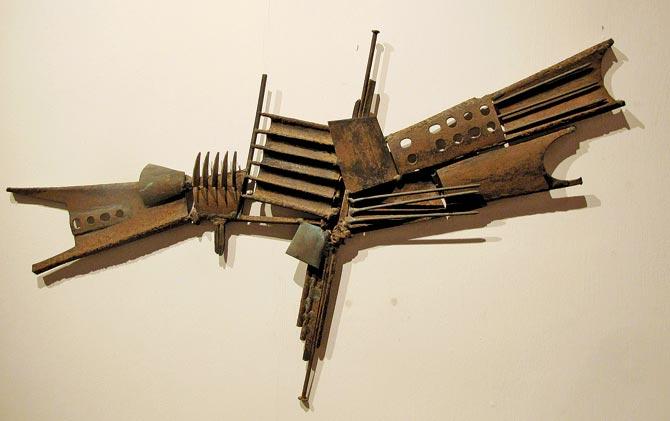

The lamp is the first thing that catches your eye as you enter the living room of her home in Parel. It was crafted in 1967. A year before that, Davierwalla had executed a piece out of found metal and glass, incorporating brass locks, drawer handles and small glass ampules. Titled Galaxy, the work is now on offer as part of Christie's upcoming South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art sale in New York. Both the lamp and Galaxy belong to the same species of works by Davierwalla, who was known to experiment extensively with a range of materials, some of which were considered unorthodox for his time.

A sketch with notes about Galaxy from Davierwalla's sketchbook. Pic Courtesy/Zarine Davierwalla

Fondly referred to as Adi, Davierwalla was one of India's pioneering Modernist sculptors and passed away in 1975 at the age of 53. He and Pilloo Pochkhanawala were among the first to set the tone for a new phase of contemporary sculpture in the country. With several works in important collections, such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), it is not often that his sculptures come up for auction.

Christie's informs us that in the last 10 years, only five Davierwalla works have been offered for sale world-over, and most have been small maquettes or models for larger pieces. Which is why, Galaxy, one of Davierwalla's larger works, has caused quite some buzz.

Galaxy (1966). Pic/Christie's

It is only in recent years that the interest in Davierwalla's legacy has been rekindled, largely through the showcase provided by two iterations of the exhibition, No Parsi is an Island: A Curatorial Re-reading Across 150 Years, in 2013 and 2016, curated by Nancy Adajania and Ranjit Hoskote. Adajania, a cultural theorist, says that when they showed sculptures and sketchbooks by Davierwalla, in the first iteration of No Parsi is an Island in Mumbai, people were amazed by how contemporary these works appeared.

"Davierwalla had been supremely well-regarded in his own time but has been forgotten. He died long before the boom in modern Indian art. The last time his works were shown to the public on a grand scale was in 1979, when Ebrahim Alkazi hosted a retrospective on Davierwalla at Jehangir Art Gallery. With No Parsi is an Island, we wanted to bring to light the lost histories of Modernism, and highlight artists who have been banished from a canon dominated by the Bombay Progressives and the Baroda school," she says.

Icarus (1970), shown as part of No Parsi is an Island: A Curatorial Re-reading Across 150 Years at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Mumbai, in 2013

Changing paths

Davierwalla was born in Sanjan, a village in Gujarat, and was sent to study at the age of six to St Joseph's Boys' School in Coonoor, where he was till he turned 18. "My father sketched through his school days; he even made little sculptures with his penknife. But, his parents were keen that he pursue a more serious profession, seeing that there was no money to be made in art," recounts Zarine.

Davierwalla made large works for commissions. This one, titled Growth, is at IIT-Bombay's campus

Graduating from Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute (VJTI), in Matunga, he worked as a pharmaceutical chemist at Continental Drug Company, then in Worli, where he met Melba Murzello, whom he would marry. "My mother was a big influence on my father's interest in art. She asked him to give up a career in pharmaceuticals and was sure that should there be financial hardships, she would be there to support him," says Zarine. At her home, Zarine is surrounded by relics of her father's legacy — the few that the family has kept after the rest were sold to collections, notably Alkazi's. A chair, a palette-shaped table, and a bust of Christ — a gift to her mother — are among those that remain.

Playing with materials

While Davierwalla learnt the basics from noted sculptor NG Pansare, he taught himself skills such as welding and metal casting. In search of material to work with, he often sought out renovation sites, of his own home and friends'.

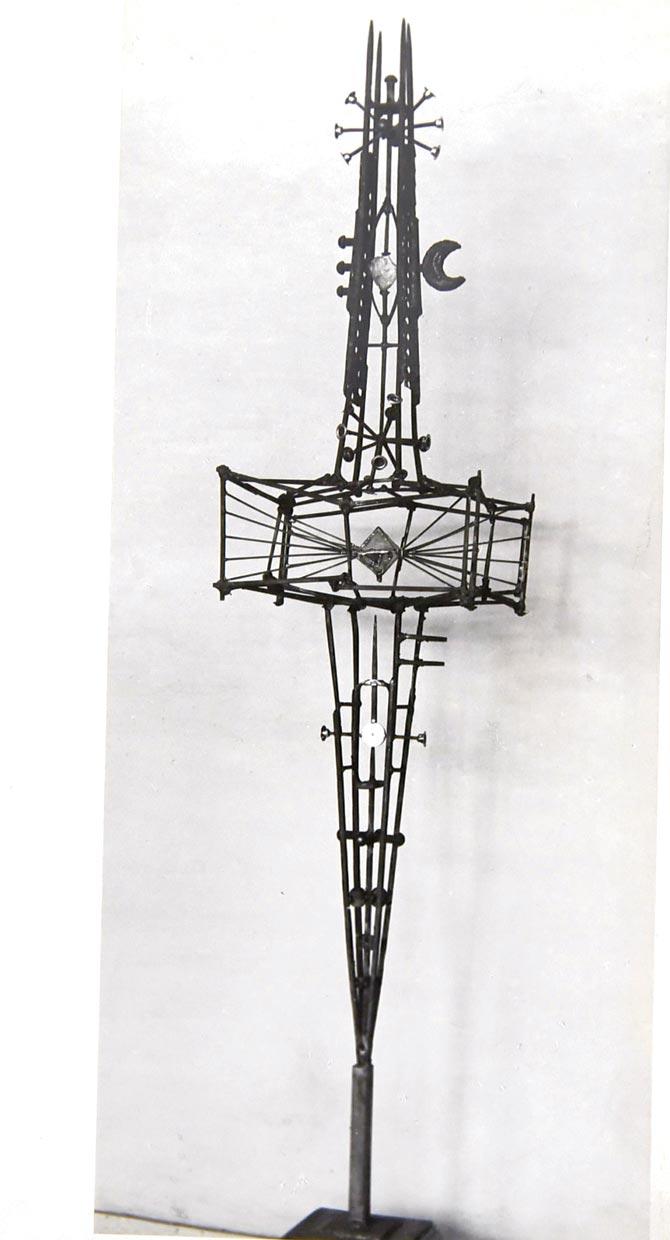

Crystal and Gold: A Monument to a Memory was made as a tribute to Dr Homi Bhabha. Pic Courtesy/Zarine Davierwall

From there, he would collect scrap wood and metal, allowing them to weather if required before using them in his sculptures. In a sketchbook from 1962, he had jotted down a few verses, among which was the line, 'In a pile of junk sheer poetry.' As much as he valued scrap, he also used new age materials, such as Plexiglas, soon after a fellowship at The Rockefeller Foundation, New York, in 1968. "We brought back stacks of Plexiglas on our return to India. Over here, he could only make a limited series since neither was Plexiglas available nor was the right kind of adhesive," says Zarine.

Noted painter Gieve Patel, a friend of Davierwalla's, says that his sculptures could be broadly described as sometimes organic, at other times geometric. "There are those that were related to the world of mathematics and ideal constructs that the human mind has fashioned. There were those that were to do with nature and growth. He was equally at ease with both of these," says Patel, who wrote the introductory essay for the 1975 monograph on Davierwalla published by Lalit Kala Akademi.

Zarine Davierwalla shows a photograph of Falling Figure, a 17-feet-long work made by her father Adi Davierwalla for the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre. The lamp Davierwalla made for her hangs on the wall. Pic/ShadabâÂÂu00c2u0080ÂÂu00c2u0088Khan

Influenced more by Western traditions of Modernist sculpture, such as those of Constantin BrâncuÈÂÂu00c2u0099i and Picasso, Davierwalla was practising at a time when sculpture struggled to be on equal footing with painting. He also drew from Greek mythology and Christian themes for the subject and titles of his works. Patel recalls his vast collection of Western classical music LPs, which included not just the masters, but contemporary composers as well.

"In the 1950s and 60s, critics from Britain and the USA made Indian artists feel uncomfortable by questioning our interest in Western art, whether classical or modern. These critics insisted that Indian artists turn to their own tradition. What they were saying was: Stay put. However, if Picasso could study African art and Matisse could turn to Persian art, then Indian artists could look at Western art. Adi and his generation were the first to strike out for this freedom to draw inspiration from anywhere, any

period," explains Patel.

Davierwalla's works range from meditative sculptures in wood to dynamic assemblages in metal. In a substantial set of works, Adajania says that Davierwalla was influenced by speculative science fiction, the climate of the Cold War, Space Age explorations and advances in robotics and cybernetics. Among her favourites, she picks Icarus. "Icarus could be seen as an autobiographical work, a young man's rebellion. The tragic and the heroic were constant themes in his art," says Adajania. She and Hoskote are planning a retrospective on the artist, as well as co-authoring a book on him in the near future.

The sad reality for sculptors such as Davierwalla is that publicly displayed sculptures are left to neglect and fall into a state of disrepair. Three such large works, including one called Surya Dev at Bhulabhai Desai Road's Ananta Housing Society, have now vanished. A Galaxy sighting is a grand occasion, therefore. Nishad Avari, head of sale, South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art, Christie's New York, says that the iconic sculpture draws from Davierwalla's scientific past and his close association with Dr Homi Bhabha and the TIFR.

"It's a dynamic monument to pioneers like Bhabha who led the technological developments of the time and the expansion of our understanding of the universe," he says.

For Zarine, ever the daughter to her sculptor father, it is far more dear. The thing she loved the most about Galaxy was its whimsicality, the way she could twirl and play with its suspended spheres.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!